Tapas ‘Bapi’ Das, among the last of the founders of Mohiner Ghoraguli whose original Bengali rock songs of life in Kolkata of the turbulent ’70s set the roadmap for Bangla bands, stayed audacious throughout the 68 years of his life. When we met him and his wife Sutapa in hospital last month, his oxygen mask had not been able to stifle his characteristic nonchalance, discussing and planning forthcoming shows with his much younger bandmates with the enthusiasm of a greenhorn. “Show dhukche?” he would ask about the status of the next concert in typical Bangla band parlance. “Dui ek din a dhuke jabe mone hochchey (should be confirmed in a few days),” someone would answer, Sutapa told us. That’s what Das, Bapida to all who knew and loved him, was. Forever devoted to his song, as outlined in this excerpt from the book, ‘Calling Elvis: Conversations with Some of Music’s Greatest, A Personal History’.

Bapida doesn’t perform as Mohiner Ghoraguli. He doesn’t think it’s ethical. Instead, he calls his troupe, comprising youngsters half his age, Mohin Ekhon, O Bondhura (Mohin Now, and Friends). They have had CDs out in 2011, 2015 and 2018. He is happy that he has been able to instil a sense of commitment among his bandmates. “All of them are aware. They realise that an artiste has a commitment to his craft and to himself/herself. It is easy to break this inner covenant citing the demands of the market place. But for those who don’t, it may so happen that your home has walls that only have a coat of Plaster of Paris and no paint. That’s the price. For me, that’s hardly a price to pay for not selling out.”

No matter. The walls of his home look nice enough with friends and fans having worked their magic with graffiti. I ask him what song they would sing if Monida were to be here today. Bapida quotes poet Jibanananda Das and says something about how it would take hundreds of years for another Mahatma Gandhi or Charu Majumdar to set foot in this country. “What happened to journalist Gauri Lankesh? See what Pune police did the other day,” he says, referring to the raids and subsequent house arrest of activists deemed to be “urban Maoists”.

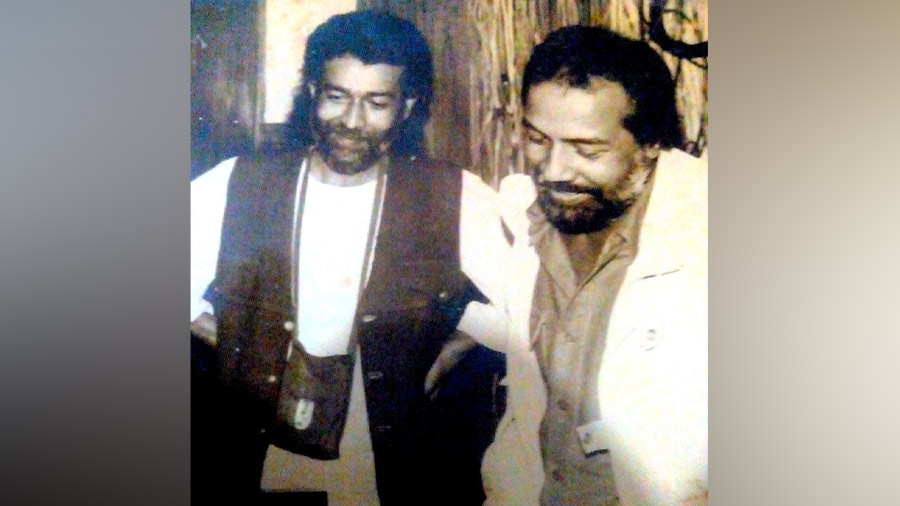

With Gautam ‘Monida’ Chattopadhyay whose idea to write songs, in Bangla, about life in Kolkata using motifs of rock music led to the formation of the one and only Mohiner Ghoraguli in 1975

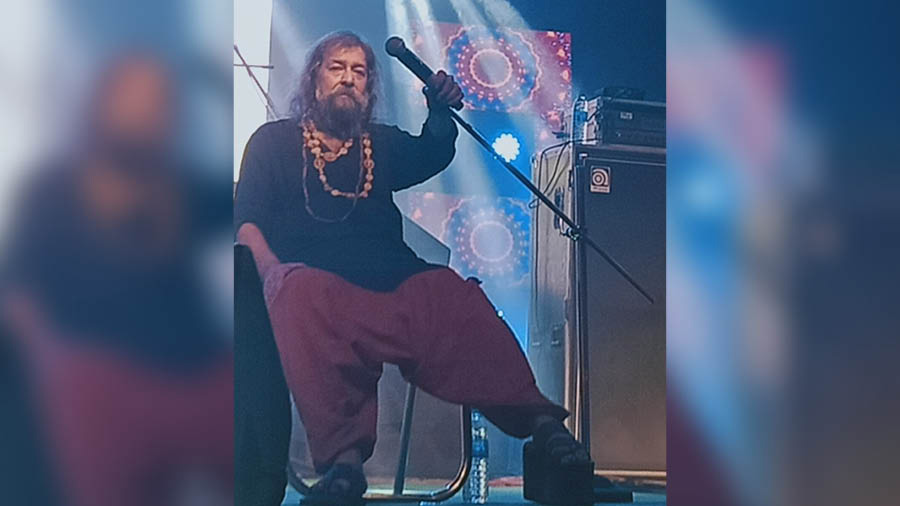

Before we leave, Bapida is generous enough to play for us a recording of one of their latest songs. Titled Bhanga Aina (Broken Mirror), the song is about the culture of projecting oneself on Facebook, he says, akin to staring at a distorted reflection of the self in a broken mirror. I note the crossover to a full-blown electric sound in the composition that is set to a propulsive beat. I would go on to experience that electric sound live exactly a year later when Mohin Ekhon O Bondhura were performing at what looked like a makeshift hall with a tin shed for roof at Lake Town on the northern fringes of Calcutta. It was to celebrate the band’s eighth and the current line-up’s third anniversary. A host of young musicians, all well-known names, had gathered there to celebrate Mohiner Ghodaguli and their music. The finale was Hay Bhalobashi. Everyone in the audience joined in for what has now come to be regarded as the “national anthem” for Bangla bands. Mobile phone flashlights were turned on, the crowd swaying to the opening riffs of the song that has been front-loaded with a sharp guitar lick. Bapida was seated, joining in at chorus, while Suman ‘Mickey’ Chatterjee sang lead vocals, ably accompanied by Prosenjit ‘PP’ Pal on synthesiser, Tannoy ‘Bittu’ Chatterjee on bass, and Neel Roy Choudhury on drums. Sudip Nag’s guitar dutifully receded to the background on cue. And we all sang along.

Bhalobashi Piccaso Bunoyel Daante

Beatles Dylan ar Beethoven sunte

Rabishankar ar Ali Akbar sune

Bhalo lage bhore kuashay ghore phirte

The full-throated rendition left behind the melancholy of Mohin’s original. Bapida had answered his calling, singing with a bunch of youngsters who weren’t even born when he wrote that song. A bridge had been built. They were singing about the same joys and yearnings, but with a renewed sense of confidence, with a bit of head-banging no less. Could they be singing about hope? How could they even dare? After all it was 2019, the year of NRC, the National Register of Citizens that seeks to determine how Indian we are. Yet, if anyone could it had to be them.

Since then, whenever I hear their songs, I think about that “friend” who did not keep his word (Kotha Diya Bondhu). About those flying horsemen who showed the way, about the rainbow of emotions that binds us to the music of the Beatles, Dylan and Ravi Shankar. This country of ours must find a way to make it worthwhile for our 19-year-olds. … (they) must be loved, nurtured and respected so that Bapi and others like him who follow can continue doing what they do best. That song yearns for good days. “Sudin kachhe esho bhalobashi eksathe shob kichhui,” it says, calling out to a future when we can all go back to liking, loving and respecting everyone and everything together.

This excerpt from ‘Calling Elvis: Conversations With Some of Music’s Greatest, A Personal History’ has been published with the permission of Speaking Tiger Books.

Calling Elvis: Book cover