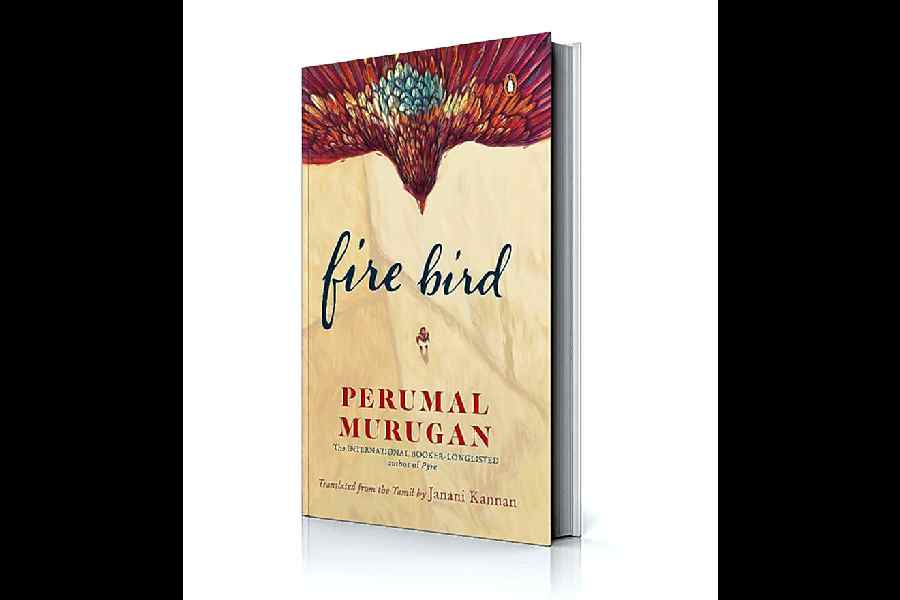

Although Perumal Murugan didn’t win the International Booker Prize this year, though he was on the longlist, he did get the language that he writes and champions a global recognition with Pukkuli, translated into Pyre by Aniruddhan Vasudevan. The Tamil scholar and literary chronicler who has written 12 novels, six collections of short stories, six anthologies of poetry, and many non-fiction books that have been translated into English hits the headlines again this year by winning the JCB Prize for Literature — announced on November 18 — for his 2012 novel Aalanda Patchi translated into English to Fire Bird by Janani Kannan, a US-based architect, translator, singer, and marathon runner.

Murugan, a former professor of Tamil at the Government Arts College in Salem Attur and Namakkal, Tamil Nadu, is known for writing on subjects that are rooted in his homeland and themes that made him go ‘dead’ once in 2015 after attracting violent attention of Hindu right wings for his novel Madhorubhagan translated to English as One Part Woman that dealt with the social stigma that a married couple faces due to their childlessness, and the lengths they go to conceive. He resurrected soon and since then has written and published books at healthy intervals, though he prefers not to talk about that phase.

With Fire Bird, which alludes to a mythical bird in Tamil, he takes a leaf out of his ancestors’ lives and tabs on the theme of migration, displacement, and the journey of finding permanence. Srinath Perur, the chair of the jury, JCB Prize for Literature, summed up the winning book as: “In Fire Bird Perumal Murugan takes a universal story of lives that are tied to land and tells it with astonishing particularity. Janani Kannan’s translation carries into English the rhythms not only of Tamil but of an entire way of being in the world.”

In this t2oS interview, Murugan talks about what resonated with the JCB jury for Fire Bird, the poignant experience of migration in an agricultural setting and sustaining this natural inclination for writing.

This year has been great for you. First, the long list in the International Booker Prize and now the win at JCB Prize for Literature. How does it feel and what does this win mean to you?

Apart from the reactions of the readers, when my writings are acknowledged with awards, a sense of fear creeps in. I find myself questioning whether I can surpass this achievement and maintain my usual writing standard. Even now, that feeling persists. The Tamil language holds a literary tradition spanning 2,000 years, encompassing modern literature that stands at a par with its ancient counterpart. The recognition bestowed upon my writings is, in essence, a significant acknowledgment for the Tamil language as a whole.

This was your third time at the JCB Prize; did the thought of winning cross your mind? What do you think impressed the jury this time?

In the first year of the JCB Prize in 2018, Poonachi made the shortlist. Subsequently, in 2019, both Aalavaayan and Arthanari earned spots on the list. This year, Aalanda Patchi secured a place for the third time. With the knowledge of the high quality of all the shortlisted novels, I approached the event without harbouring great expectations. The jury’s short notes offer insights into the merits of each novel. When choosing from five commendable works, certain aspects of a novel may capture the jury’s attention. In the case of Aalanda Patchi, I believe the theme of ‘migration’ might have resonated with the jury.

While Pyre got you an international recognition, Fire Bird puts national focus on you. How much do you think these recognitions help in putting across your writings in Tamil and urge you to keep writing?

Writing has always come naturally to me. Since my youth, I have chosen literature as the medium to express my innermost thoughts to the public. I have maintained a consistent habit of writing sporadically, and I hope to sustain this natural inclination. It’s essential for me to be cautious not to let recognition affect my process, and that’s my only consideration.

Fire Bird is also inspired by your life in some ways. Can you tell us more about that aspect of the book?

My first novel, Aeru Veil, draws heavily from my personal life, delving into the internal migration within the same village — a phenomenon I witnessed during my childhood. In Aalanda Patchi, the narrative centres around the migration of my ancestors to a distant village. This time, the story is based on accounts I heard from others. Numerous individuals, I have learned about through stories and those I have personally encountered, find their way into the characters of this novel. The poignant experience of migration in an agricultural setting is a theme I have personally lived through, and I attempt to explore and reconcile this through various facets in my novels.

Throughout Fire Bird we also see a beautiful camaraderie between Muthuannan and Kuppanna, transcending boundaries. Tell us about that bond.

In a society structured around caste, a defined boundary shapes the camaraderie between individuals. Love and connection exist within the confines of this boundary, and though attempts are made to break free, individuals often find themselves returning to stand within their limits. Crossing this boundary entirely is a challenge, and when I explored this theme in my writing, I contemplated how individuals might fare if they were able to overcome this limitation completely. My observations draw from the experiences of many individuals within the agricultural community.

You wrote Aalanda Patchi in 2012, how does the new focus on the novel feel? And after more than a decade now, do you think you would have changed anything in the original novel?

A creative work, crafted years ago, takes on a new life when discovered by fresh readers. The wings of Aalanda Patchi are robust, poised to manifest in novel forms, attracting renewed attention. The JCB Prize recognition ensures it reaches a broader audience, bringing me great joy. Over the past decade, reader feedback has indicated a desire for more elaboration on land reform in my works. Despite this, I’ve chosen not to alter anything, maintaining the integrity of the original narrative.

A lot of trust is involved when translations happen. Tell us about the process of translation with Janani Kannan.

She initially translated the novel Aeru Veil, gaining valuable insights into both agricultural life and family dynamics. This understanding paved the way for her to delve into Aalanda Patchi. The process began with an email inquiry about the title, Aalanda Patchi.

Our extensive discussions included folklore about the bird, reflecting Janani’s curiosity to gather as much information as possible from me. Her eagerness to comprehend the world unveiled in the novel greatly contributed to the quality of the translation.

Your last novel was Neduneram, released in 2022. What are you working on next?

Currently, I am engaged in writing short stories and contemplating the creation of a brief novel. If time allows, I believe I could complete the novel in the days ahead.

Perumal’s other works

The Season of Palm (2000)

One Part Woman (2010)

Pyre (2013)

The Goat Thief (2017)

Poonachi: Or the Story of a Black Goat (2016)

other notable translations

Geetanjali Shree's Tomb of Sand (International Booker Prize)Khalid Jawed's The Paradise of Food (JCB Prize 2022)

Manoranjan Byapari's Interrogating my Chandal Life: An Autobiography of a Dalit (Hindu Prize)

M. Mukundan's Delhi: A Soliloquy (JCB Prize 2021)

Madhuri Vijay's The Far Field (JCB Prize 2019)