The occasion is the 50th anniversary of Satyajit Ray’s film adaptation of Goopy Gayen Bagha Bayen. The documentary being screened is not on the writer, nor the director, nor any of the actors — all long dead. It is on the director of photography, Soumendu Roy.

Roy, 86, had no formal training in cinematography. He belongs to a family that was employed in “decent, respectable professions” and he was expected to study jute technology after graduation. Yes, as specific as that. His interest in photography was sparked by his elder brother as well as his first camera, a Kodak Brownie that was a gift from his sister for passing his Class X boards. What happened thereafter was a communion of a benevolent universe and some free will. A family connection landed him a job at the Technicians’ Studio in Tollygunge — Calcutta’s studio district — when he was still in college, and Roy became a camera caretaker. His filmic career had begun.

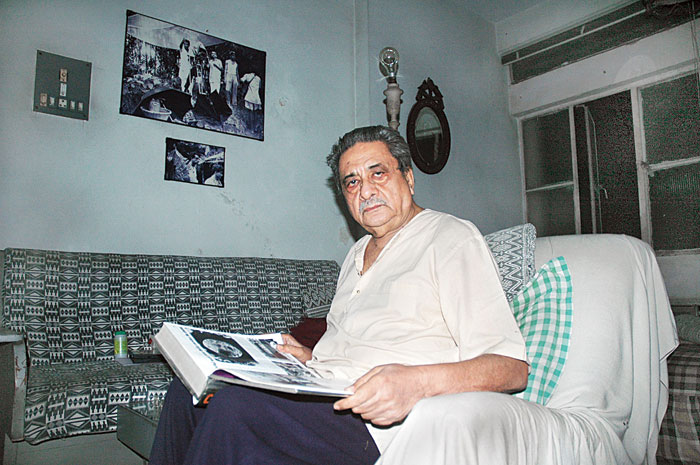

Roy’s onscreen image too is predominantly white — dressed in white with a white mane. He speaks slowly, his sentences well thought out. The documentary was shot nearly a decade ago; Roy is now confined to his house because of ill health. Courtesy: Ranajit Nandy

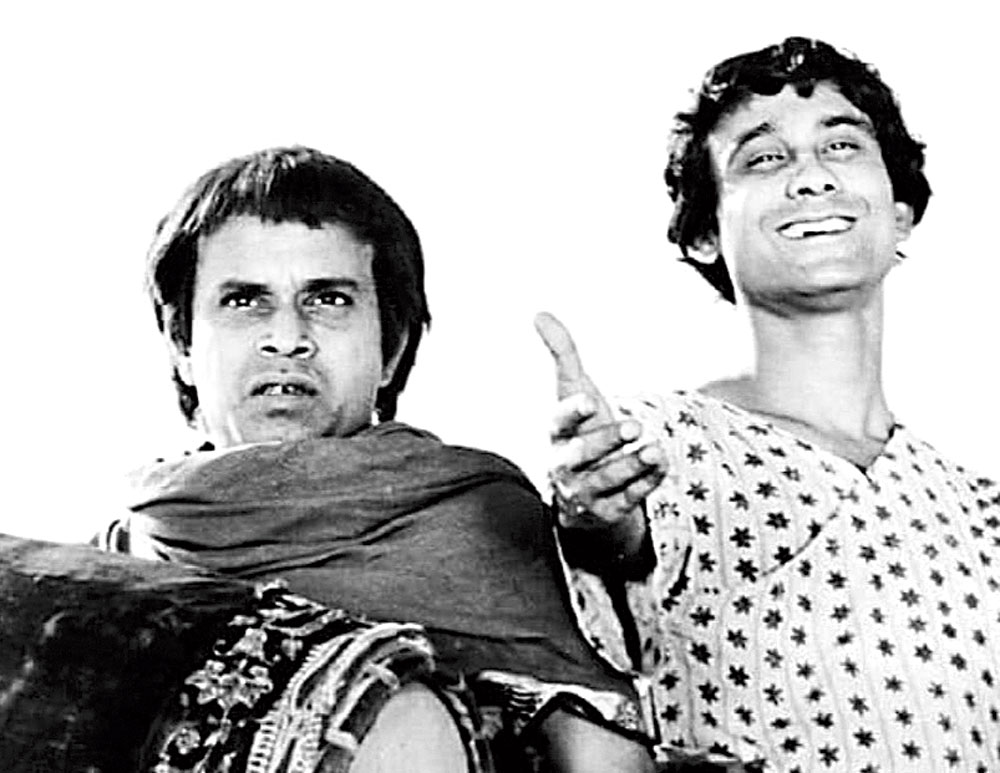

The documentary by Arindam Saha Sardar, just like Roy’s first films, opens in black-and-white. Roy in conversation with his interviewer is shown outdoors, in locations that echo his films. While he is talking about Goopy Gayen Bagha Bayen, for example, he is sitting before a bamboo grove. After all, the shot that drove the film — the bhooter raja or king of ghosts granting Bagha and Goopy three wishes — was shot in a bamboo grove.

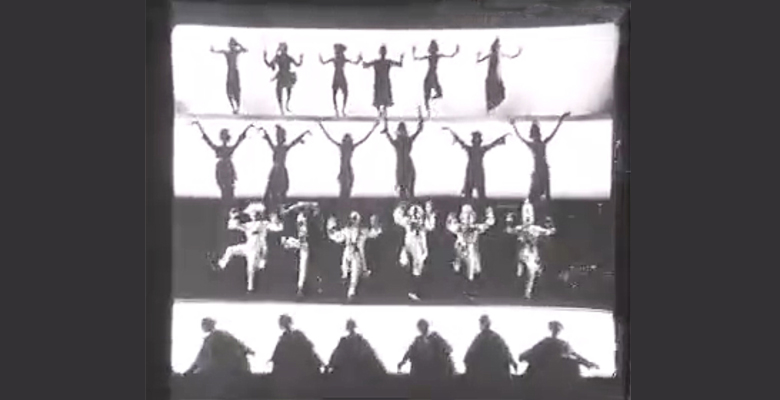

That scene gave Roy a chance to experiment. There is a sequence where we can see four rows of ghosts dancing one above the other. “Actually, four different scenes were shot with dancers — some of them wearing masks — turned into negatives and then spliced together, one above the other,” Roy tells his interviewer with pride, before going on to lament that most of his later films were nowhere near as interesting to shoot.

Roy talks about how challenging it was to shoot Goopy Gayen. There are two kingdoms shown in the film — the good Shundi and the bad Halla. Ray wanted everyone in Shundi to be dressed in white while the people in Halla would be in dark colours.

“Set designer Banshi Chandragupta came up with a beautiful set for the Shundi royal court with a black-and-white chequered floor,” says Roy. But the problem was that it was too white, as Ray wanted. “The colour white was then avoided in films as it was difficult to shoot. If we had to shoot anything white it would be soaked in tea to give it a tinge,” Roy explains.

Roy’s onscreen image too is predominantly white — dressed in white with a white mane. He speaks slowly, his sentences well thought out. The documentary was shot nearly a decade ago; Roy is now confined to his house because of ill health.

Roy’s first feature film came to him by accident. It was Rabindranath Tagore’s birth centenary — 1961 — and the government wanted Ray to make a documentary on the legend. Ray also wanted to make a film based on three short stories by Tagore. Roy shot the documentary and Subrata Mitra was supposed to shoot the feature film. But Mitra was indisposed and the camera was handed over to Roy for the film, Teen Kanya.

“The film had three stories. The Postmaster was a tragedy and therefore shot with cloudy skies, even the interior shots were dark with dim sources of light. Samapti (a romantic comedy) I shot realistically, while for Monihara, a supernatural story, I used surreal lighting,” says Roy.

As Roy’s filmography moves from black-and-white to colour, so does the documentary. People thought Asani Sanket, a film on the Bengal famine, should be shot in black-and-white. But Ray wanted to do it in colour. “He asked me if I could handle colour and I said I could,” Roy reminisces. Asani Sanket is the first film Roy shot in colour. He talks about a particularly challenging scene — a half-lit shot of one of the main characters as the sun sets behind her. “The light meter said the film was underexposed. We had never shot in such low light but Ray gave me the go-ahead and I shot it that way. When we developed it, it was exactly as Ray had visualised it,” says the veteran cinematographer.

As Roy decodes his craft through the documentary, you get the feeling he was getting ready even a decade ago to hand over the baton. It is this generosity of spirit that prompted him recently to hand over all scripts, photographs and other memorabilia collected in the course of his long career to Saha Sardar for archiving. The history of cinema should be the richer for it.