Actually, you might want to read this story as a dream sequence, the kind we know from films. A spotlight, perhaps some music, and a mysterious figure standing so close and yet so far — the distance between sleep and waking, wanting and worshipping. This is that kind of story.

The very first time Sushil Saha saw her, it was the early 1960s. Saha, not yet 20, had watched the trailer of a film, Harano Din, at Picture Palace theatre in Khulna — then in East Pakistan and now in Bangladesh. And there she was dressed like a gypsy, tambourine in hand, whirling away to the song Ami Roopnagarer rajkanya rooper jadu enechhi... I am the princess of Roopnagar and I bring with me the magic of beauty.

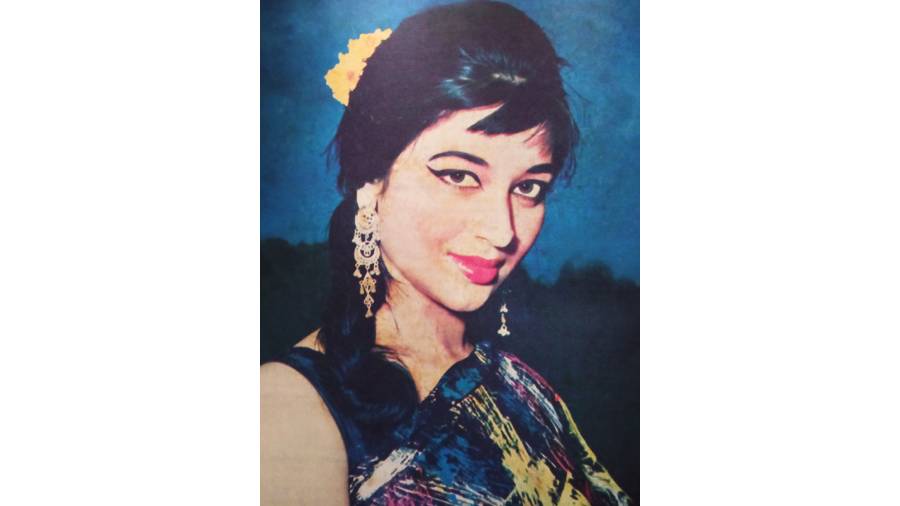

When I look up the film and the song sequence, I see a tall, lean girl with an intelligent face, big eyes and a sparkling smile. As filmi grammar goes, this one is well within my syllabus. Setting, costume, gestures — this could have been another Anjana Bhowmick or Nimmi film, except that it is not. This is an East Pakistan production and the actor is Jharna Basak.

Jharna debuted in films as a 13-year-old, acted in Bengali and Urdu films, at some point was christened Shabnam by (Bangladeshi director) Captain Ehtesham and, in 1968, after much dithering — she couldn’t read or speak any Urdu and wrote down her Urdu dialogues in Bengali script — moved to West Pakistan. Even after the birth of Bangladesh in 1971, Shabnam did not move back.

The daughter of a football referee from Dhaka, Nani Basak, she learnt Urdu, went on to act in more than 175 Urdu films and remained one of the leading ladies of Pakistani cinema for three decades. “Shabnam was to reach heights of stardom rarely achieved by any other actress,” writes Mushtaq Gazdar in his book Pakistan Cinema 1947-1997.

Saha moved to India in 1970, continued his studies, worked, lived his life in all its realities, but he did not entirely emerge from the dream of Shabnam.

“I am not a fan,” he clarifies when I speak to him, over phone, having learnt that he has written about the actor in his book Amar Bangladesh. In the course of our conversations, I begin to understand that to him Shabnam represents a time, a land, a life and its magic.

In 2010, he was still working as a librarian when Saha had occasion to visit Bangladesh with his family. Saha’s Bangladesh connection is somewhat like this — in the last many years he has edited several books on Bangladesh, and written two, time and again he pays a visit and has throughout maintained his ties with friends there. The late poet Sankha Ghosh described Saha thus: “The lockless bridge between this Bengal and that.”

Every time Saha visited Bangladesh after that, he asked around if someone, anyone, could facilitate a meeting with Shabnam.

Saha’s trip to Dhaka in 2018 was no different. His friend and the then Bangladesh film archive chairman, Jahangir Mohammed, asked him if there was anything he wished for and Saha said he would like to meet Shabnam. This time the stars — in the heavens — were not napping.

You might scramble through Shabnam’s films — Chanda, Talash, Kajal, Saagar, Karwan, Darshan, Aina, Aakhri Station (Shabnam’s personal favourite) — and still you won’t be able to see what Saha saw.

But before we return to his dream sequence, it is important we understand its significance. To arrive at that significance we need a measure of the film industry of Pakistan. Only then can we appreciate Shabnam’s success.

Till 1971, Pakistani cinema was made up of Punjabi, Urdu, Bengali and Sindhi films. The government-run East Pakistan Film Development Corporation in Dhaka had the first colour laboratory in all of Pakistan. Even after Pakistan split into two, not everybody from East Pakistan who was in West Pakistan was quick to return.

In the essay, Mirrors of Movement, Lotte Hoek reproduces portions of his interview with Bengali cinematographer Afzal Chowdhury, who stayed on in independent Pakistan until 1980. Chowdhury says, “It was very nice... We had a group, a sort of Bengali group you can say: famous music director Robin Ghosh and his wife Shabnam (she was a top heroine of Pakistan in those days); myself; and there was Nuzrul Islam and Rahman; and the very top hero of those days [Nadeem]. He was from Dhaka but not actually Bengali; he was from Hyderabad, South [India].”

On May 13, 1978, five armed men looted Shabnam’s house in Gulberg in Lahore. They also raped her. They were from “influential families”; General Zia-ul Haq commuted their death sentence. In 1999, Shabnam left Pakistan for good.

That day at Shabnam’s house in Dhaka, she spoke to Saha about how before she moved to West Pakistan she was making Rs 600-700 per film, how when she asked for Rs 25,000 per film the film fraternity of East Pakistan tried to effect a boycott. But then director-producer Khan Ataur Rahman offered her Rs 50,000 for Raja Sanyasi, a film on the Bhawal case of the 1930s-40s. Says Saha, “She told me, ‘But every producer is not Rahman saheb. That is why I left for West Pakistan.’”

Shabnam reiterated that despite belonging to a minority community, she was born a Hindu and thereafter married into a Christian family, her professionalism was acknowledged and celebrated in independent Pakistan. She won the Nigar Award — often described as Pakistan’s Academy Award — 13 times.

Saha’s visit was cut short because of logistical reasons. But, apparently, he too was in a hurry to leave. Why? Saha seems to have this innate sense of balance. Of? Of dream and reality. He tells me he stayed just long enough for the dream to live on.