Three pigeons peeped down from the upper reaches of Victoria Memorial’s Eastern Quadrangle as the ceremonial introductions continued. They would have been lost in the darkness but for the marble of the walls. Below, it was all light and brightness and an expectant packed silence. Behind the raised stage was a smart ivory form, which, once the eyes had adjusted to the light and dark, turned out to be the middle-aged Lord Cornwallis — Governor-General of British India — in Roman tunic, with receding hairline and gladiatorial six pack, a twig in one hand, a sword in another, and Fortitude and Prudence at his feet.

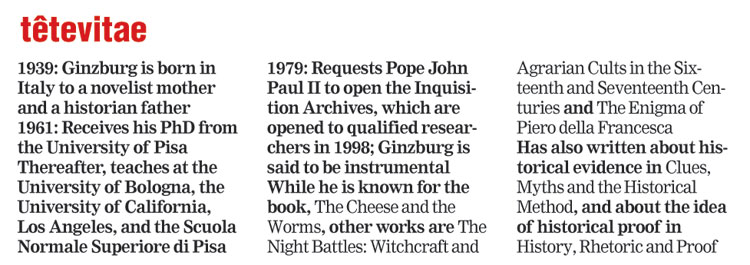

The speaker that evening was the Italian historian, Carlo Ginzburg, hailed by those in the know as “a pioneer of the micro-historical method”. Younger members of the audience seemed to recognise him as “the cheese and worms guy”. (The Cheese and the Worms is a seminal book by him.) He was on stage and in conversation with Naveen Kishore, who is the publisher of Seagull Books.

Ginzburg started to talk. Now, there are all kinds of speakers. Some speak to impress an audience, some like to entertain, some are too earnest, some too aloof... Our man here seemed comfortable to be himself and himself is a happy scholarship. Make no mistake, not all of what he said was easy to grasp, especially if you were not from the discipline; neither did he try to break it down for his audience, make all that complex scholarship easy to ingest. But what he did do was speak from an equal place, the kind that puts the onus on the listener to assimilate and assimilate responsibly.

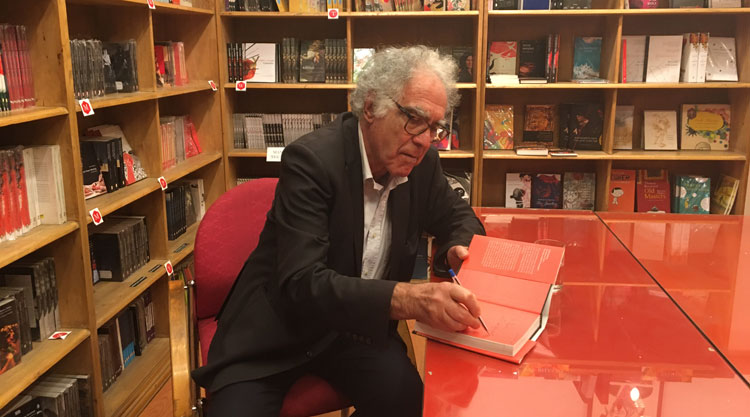

Two days before the programme at Victoria Memorial, when I met Ginzburg for a longish chat at the Seagull bookstore in south Calcutta, he told me how he does not believe in being condescending or elitist in his addresses. “I hate this,” he said emphatically. And went on to add, “My motto is ‘Truffles for everybody.’ Truffles are very good, very rare, very expensive. I try to share highly complicated research by sharing the trajectory to the results because that is deeply engaging… Why are people, including children, fascinated by archaeology; not just by what can be found underground but also by the act of digging.”

Ginzburg, 79, is professor emeritus at Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, and the University of California, Los Angeles. He is a man of upright carriage, firm handshake, nails cut very close to the skin, neat no-nonsense professorial attire, disobedient gravity defying cumulus hair and copious brows to match. The sound of his voice is a bit like sandpaper against a wall, only pleasing, and though an Italian accent flavours his English, his enunciation is clear.

The good professor arrived in Calcutta from Bologna the night before the CBI descended on the then Calcutta police commissioner, Rajeev Kumar. The day we meet, chief minister Mamata Banerjee is sitting on her Save India dharna and the city is pulsating with mixed emotions. We talk about the way things are — the Centre and state tug of war, the long shadow of Hindutva, the threat to minorities, impending elections and the consequent shrill politicking. I tell him how in the middle of it all when I learnt about his visit and read about his book, Fear Reverence Terror: Five Essays in Political Iconography (2017, Seagull), it seemed so pat, and he starts to talk about what Thomas Hobbes had to say about fear, state and religion.

Picking up a copy of the book, which is lying around, he turns the pages till he finds the chapter titled “Reading Hobbes Today”. He then finds the page with the image of the frontispiece of Hobbes’ book, Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil. It is an iconic representation of a man mountain. He has a crown on his head, a sword in one hand and a hooked pastoral staff in the other. He appears hirsute, but on closer look, all that hair turns out to be countless human figures looking up at him.

What follows is a masterclass. Ginzburg reads his own lines: “Leviathan, an artificial creation, stands against those who, through their covenant, created it — those he is made of — as an awesome and threatening object.” He invokes Roman historian Tacitus and a Latin phrase he used, “fingunt simul creduntque”, meaning, they make it up and at the same time they believe in it. He points out what Hobbes said about the power of the State being based on strength and awe. And goes on about how Hobbes argued that religion was born of fear. And then he elaborates on the ambiguity that permeates this concept of fear.

Latin, Hebrew, philosophy, theology, suddenly the air is thick. Ginzburg talks about the Latin word for fear in the Bible, timor, and invokes an older word, the Hebrew word yir’ah that suggests fear and reverence. He says the Latin etymology of the word “reverence” goes back to the word “vereor”, which is “kind of religious fear”. “So you can have fear without religious connotations and fear with religious connotations. And a word implying both,” he says. And then just like that he cuts through all theory and brings the hammer down on the nail-head. He says, “This is the point that is at the centre of our world — the ambiguity of secularism. And this is one of the running themes of the book, secularism as an ongoing process and the ambiguity of the process.”

Somewhere in between all talk of empathy and philology, rhetoric and casuistry, I tell him a friend wants to know if microhistory is the history of the subaltern. He replies, “No. The prefix ‘micro’ is not related to the dimension, either literal or symbolic, of the subject. It is related to the microscopic approach to any subject, basically cases.”

Source: The Telegraph

Speaking about cases in general, Ginzburg talks about the “case of the Kitchener poster”. I had been drawn to the title of Ginzburg’s essay on it — “Your Country Needs You”. It had smacked of the patriotic trope peddled by Right-wingers in India today. The essay is about a poster representing military governor of Egypt-turned-Britain’s secretary of war, Lord Kitchener, that was issued by the British government in 1914. The image shows Kitchener’s face and a forefinger pointed at the onlooker and the following words beneath: “Wants You” in grey. And “Join Your Country’s Army!” in red. When I read the essay, I had been reminded of an image of Prime Minister Narendra Modi from government posters. It showed him arms folded, looking directly into the viewer’s eye, very resonant of Swami Vivekananda’s Chicago pose. I show Ginzburg the visuals on my phone, and he tells me about German art historian Aby Warburg’s notion of pathosformeln or the formulas of emotions.

He continues, “The pointed finger is a pathosformeln. The foreshortening is a device that emphasises distance between actor and viewer, and also abolishes it.” He picks up the book again and brings up a visual of an advertisement of Pure Virginia cigarettes. It shows a man in a suit, staring straight at the viewer, his finger pointed, exactly as in the Kitchener poster except that it is from 1910 and is selling lights. “Ancient art. Religious art. Secular, commercial art. And then art selling the war. Mark the continuity of gestures,” says Ginzburg.

There is a lull in the conversation. I am thinking of the folded arms and the professor is just pausing. When he starts to speak it is about the importance of questions. He says he oftentimes starts from answers and then goes back working out the questions and in his characteristic style tells me a story. “Many years ago, I entered a museum and saw an unknown painting and I said, ‘Guernica’ [a painting by Pablo Picasso]. In a way the answer emerged before any question.” He knew it instinctively and some of the questions he worked out or question-answers, if you will, he put down in his essay, “The Sword And The Lightbulb”. He looks at me and says impassionedly, “I said an answer but you have to look for a question.”

And then like Holmes to Watson he adds, “People producing a piece of evidence are unable to control one hundred per cent of it. There is always some kind of residual which can be read in a way different than was intended. There are always some cracks in the evidence.”

I take my leave of Ginzburg that day, wondering what the crowd at Victoria Memorial will ask him. Two days later, at the end of the programme, an engrossed audience raises questions that are almost entirely academic. What remains unstated and perhaps unconnected for the moment are the questions socio-political. As the audience bursts into an applause, the three sleepless pigeons change perch. Lord Cornwallis looks plain smug.