Sampath Kumar’s busy study in his Purna Das Road home is a reflection of his mind. Books compete with legal documents here. The walls are decorated with stunning photographs and elegant paintings. The notebook that Kumar keeps near his laptop helps organise his several selves — businessman, lawyer, author, photographer, painter and poet. Born in 1952, the polymath has kept up with the times, but he has also never forsaken tradition. When asked how he balances his many interests and professions, Kumar says, “Different interests can exist simultaneously without conflict. You have 10 fingers, but they don’t fight while doing jobs that supplement each other, right?” In a freewheeling conversation with My Kolkata, Kumar explains how he brings the past to the plentiful present of his multitudinous life.

Once upon a time in Kolkata

The Kolkata roots of Kumar’s family are a century old. “My family was full of civil servants and lawyers,” says Kumar, “but one of my uncles had connections with big factories. Once he started trading in coal, he moved from Tamil Nadu to Kolkata, and my father soon joined his business.” Growing up, Kumar paid deep attention to the pre-Independence history of his family that he was told. He heard stories of how his parents had left behind a life of great comfort and luxury to start from scratch in Kolkata. “We were living in Kolkata, but my father was posted in Raipur. He had to run two homes,” Kumar tells us.

“I have seen two different Indias,” says Kumar. “When I was young, we had no wealth as a country. Everyone struggled except a few privileged ones.” The Kolkata that Kumar grew up in, for instance, was vastly different from the one he sees today. Back then, a second-class tram ride from his Kalighat home to National High School in Hazra would cost only five paise. “But I preferred saving that money for candy, so I would walk every day. I’d enjoy running from my home to the Royal Calcutta Turf Club and back. There was no stress. Kolkata had an easy life.”

After graduating as a commerce student from Asutosh College, Kumar studied law at Hazra Law College and textile technology in Mumbai. “I next joined the Sarabhai Group, which then had an Adani or Ambani-like status. We were among the first to computerise our business. We shared this knowhow with many companies. It was a nice job, but it got boring.” In an effort to resist stagnation, Kumar transformed his life by becoming part of the West Bengal Bar Council in 1976. He soon began practising as an advocate in the Supreme Court.

Kumar with President Pranab Mukherjee

Despite working alongside legal luminaries — Kumar once assisted senior lawyers like Harish Salve, Shanti Bhushan and K.K. Venugopal — he felt bored again. “So, I started a business,” he chuckles. After having been in charge of the Sarabhai Group’s dyestuff division, Kumar’s foray into the pigment industry seemed like a natural progression. He says, “Painting was in my genes. I came from a family of painters. I started dabbling in colours as a child. When you understand colours as a painter, the pigment business becomes easier.”

Kumar quickly tasted success. “I was the only Tamilian to have stepped into this trade. We gave the right technology to the right people. We grew fast and were soon doing business worth a few crores every month, with branches in Delhi, Chennai and Kanpur.” After having hit its peak, the graph of Kumar’s growth sadly began to taper. He eventually sold his factory space on Kustia road to Sanjeev Goenka’s CESC group and moved his work to Bantala. “The Goenkas shifted their electricity warehouse there, and that is where Quest Mall stands today.”

A man of many parts

While in the pigment business, Kumar also served as the national chairman of the Council for Leather Exports. This meant he had to work closely with the government and travel frequently. “For this post, I needed to constantly observe global leaders and keep myself updated. This involved travelling to Europe multiple times a year. I helped conceptualise the Leather Complex in Bantala, and was even a part of Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee’s delegation to Italy. I had taken the former chief minister to several futuristic design centres, including that of Gucci.”

Kumar’s Italian connection runs deeper. In 2006, once the building of the Leather Complex was complete, Kumar received a call from the Italian ambassador to India. “He told me that their Prime Minister wanted to honour me with an Italian Knighthood in Delhi.” Till date, Kumar is the only Asian to have ever received the second-highest civilian award in Italy. Never one to rest on his laurels, Kumar says, “You keep crossing these milestones but you don't turn your head back every time. You only see the next thing you need to do. But that said, the award did motivate my children, and the fact that I could be a reason for their improvement is a very big thing. You can’t change the world, but you can change the small world around you.”

Kumar is the only Indian to have ever received the second-highest civilian award in Italy

Kumar’s daily drives to the Leather Complex helped him write. “The journey would take at least an hour, and the roads were terrible. My mind was free because I was being driven. I soon started writing short poems and sharing them.” Seeing the appreciation his poems were receiving, Kumar decided to hone his craft. “I write about anything and everything, covering subjects like surrogacy, female foeticide, even lesbians getting stoned to death in Saudi Arabia. There is no bar. I spontaneously write on anything that catches my eye.”

In his book, Tamils of Bengal, Kumar writes about how people from Tamil Nadu came to West Bengal. “In the 1950s and 1960s, Brahmins left Tamil Nadu en masse because of political reasons. Some settled in Mumbai’s Matunga area, some in Delhi, and many came to Kolkata.” Since flights were impossibly expensive in those days, people thronged the city in trains, says Kumar: “It would take three days for people to reach Howrah station from Madras Central. Kolkata was then seen as a land of opportunity by many Tamilians.”

Kumar also makes mention of Ramakrishna Lunch Home and Komala Vilas. “These were among the first Tamil messes. The former was called Patima Hotel. ‘Patima’ means grandmother in Tamil.” The Lake Market area, he tells us, was once populated with more than two lakh Tamilians. Vocational training was given as much emphasis as providing shelter. “When the British left, they left much of their business to their munshis, who were mostly Marwaris. While the Marwaris had business acumen, they lacked communication skills. Tamilians may not have been comfortable with Hindi, but they had no problem with English. They easily got jobs.”

Kumar makes mention of Ramakrishna Lunch Home and Komala Vilas. ‘These were among the first Tamil messes.’

Besides Tamils of Bengal, Kumar has also released an anthology of Tamil poems, Karaiyorak Kavidhaigal. He is presently translating the work of acclaimed Tamil poet Subramaniya Bharathiyar. “Interestingly, Ramakrishna Lunch Home stands on Kavi Bharati Sarani. The road is named after him. This will be a multilingual translation, roping in many famous poets from around the world. Sahitya Akademi is also tracking this project very closely.” This translation project, Kumar says, has helped him reconnect with his mother tongue: “It was like riding a cycle. Even if you have forgotten how to do it, it comes back to you easily when you restart.”

Wanting to rediscover his Tamil roots, Kumar even travelled to his father’s village in Kumbakonam for the first time a few years ago. “I only had to say my great grandfather's name, and I was immediately hugged with warmth. Some bonds transcend generations.” Kumar adds that he loves starting his day with a south Indian breakfast. He also likes wearing his veshti for traditional programmes. “Food and attire are crucial habits for any society. The language, food and tradition you have grown up with will always remain special.” Currently, Kumar heads Bharathi Tamil Sangam, the oldest and largest Tamil association in Kolkata.

Despite being immersed in Tamil culture, Kumar says his Bengali identity is as strong as his Tamil one. “My wife, Radha, and I are both from the same area in Tamil Nadu, but we were born in Kolkata. We lived in the same locality, and were both married in this city. I speak to her in English, Tamil and Bangla, depending on my mood,” says Kumar with a smile.

Booking up his schedule

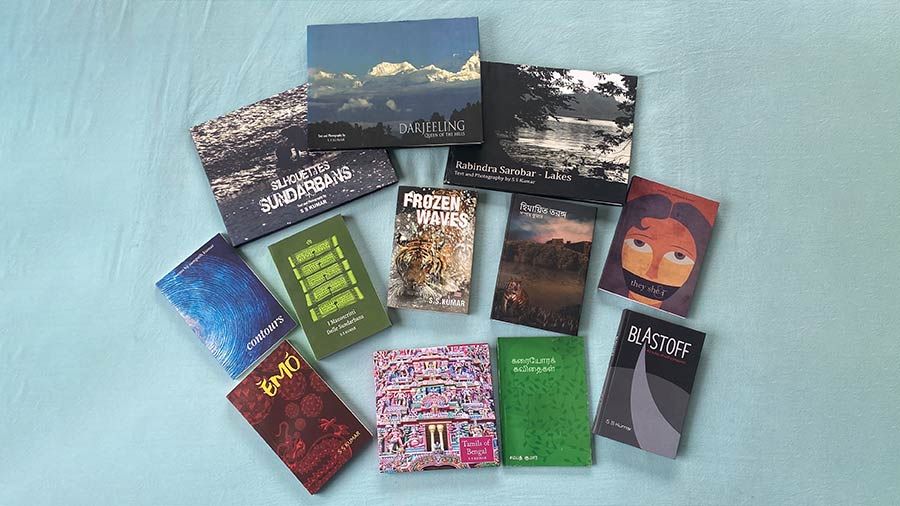

Some of Kumar’s books

Unhappy with the polluting practices of his industry, Kumar sold his Bantala factory in 2016, and once he had resumed his legal practice, he began spending all his spare time writing. His ever-expanding body of works now includes coffee-table books, novels and two volumes of English poetry. Much like his novel, Frozen Waves, his first coffee-table book, Silhouettes of Sundarbans, is also set in the mangrove forest. Kumar had first travelled to the area with his analogue camera 45 years ago. Decades later, he went back to the Piyali region of the Sunderbans as a Rotary member to start a school. Today, it provides education to over 700 rescued girls who were earlier sold across the border. “I’m fascinated by how small initiatives have changed the destiny of many and it is this butterfly effect that I want to replicate.”

In his second coffee-table book, Darjeeling - Queen of the Hills, Kumar documented his extensive travels through the entire district. The third one called Rabindra Sarobar – Lakes highlighted how Rabindra Sarobar had helped lay south Kolkata’s foundations. “This man-made lake helped create the entire stretch from Ballygunge to Manohar Pukur. A lot of Bengalis went to the UK to study law after the World Wars. When they returned, they were ostracised because you were thought of as impure if you had crossed the sea. Hence, these barristers ended up building bungalows, and all of south Calcutta once comprised their standalone houses.” He later laments, “Of course, promoters have stepped in and demolished these bungalows. You only have multi-storeyed buildings here now.”

All the pictures in his coffee-table books are taken by Kumar himself

All the pictures in his coffee-table books are taken by Kumar himself. An avid photographer, he is also a member of The Royal Photographic Society in London. The walls of his house are dotted with pictures he and his son, Arvind, have clicked. “Viren J. Shah, the then-governor of West Bengal had once seen my photographs and said, ‘Isko rakhke kya fayeda? (What use are these pictures if they are just left lying around?) You have to show them to people!’ So, I spoke to the secretary-curator of Victoria Memorial and my first photography exhibition was also the first private photographic exhibition to be held in the Victoria Memorial Hall.”

Kumar’s second photography exhibition, one that he had clubbed with the launch of Silhouettes of Sundarbans, was held at the equally historic Town Hall, shortly after it had been freshly repainted and renovated under Alapan Bandyopadhyay’s initiative. “I remember Russi Modi having to climb the stairs because the lift wasn’t ready at the time. It was a packed hall. Somnath Chatterjee couldn’t make it because he was admitted to a hospital at the time, but he sent me a beautiful letter.”

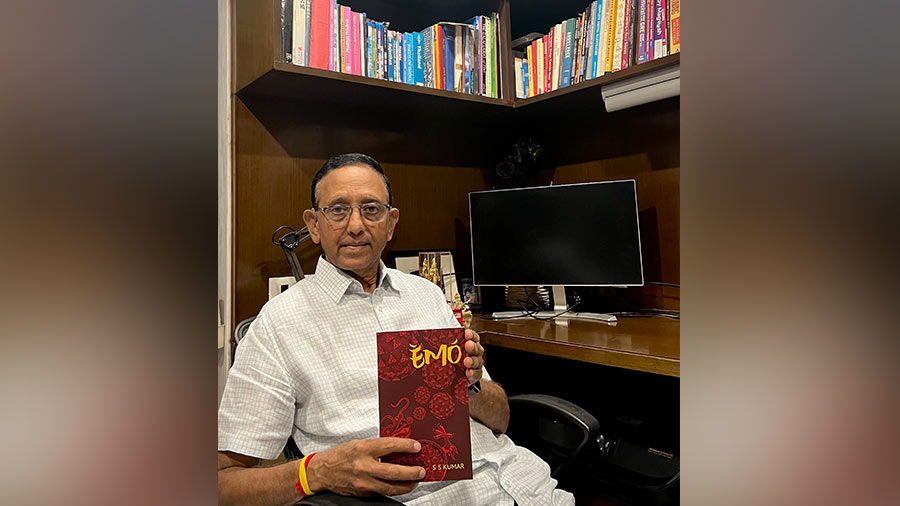

Kumar with his latest book, ‘Èmó’

Kumar’s latest book, Èmó, is expected to launch next month. It fictionalises the MH370 flight disappearance. “Since it didn’t sink in the ocean, nor was it seen anywhere, I give this man-made disaster a storyline.” The cover of his book has been designed by his daughter, Vinita, who took to painting like her father. Kumar, for his part, is already working hard on his next book. “This one is a 60-year-old story about villages in Tamil Nadu. Much of it is based on the memories I have of my old village.” Besides full-length books, Kumar also regularly writes a blog that has over 2,000 entries on various topics.

With his son now having relocated to Delhi, Kumar wants to visit him more often and practises again in the Supreme Court. “If I have some days free, I would also like to take my camera and go to the jungle!” When asked about his constant juggling, Kumar says, “I don’t see any conflict here. I already have another worm in my head now – vlogging!”