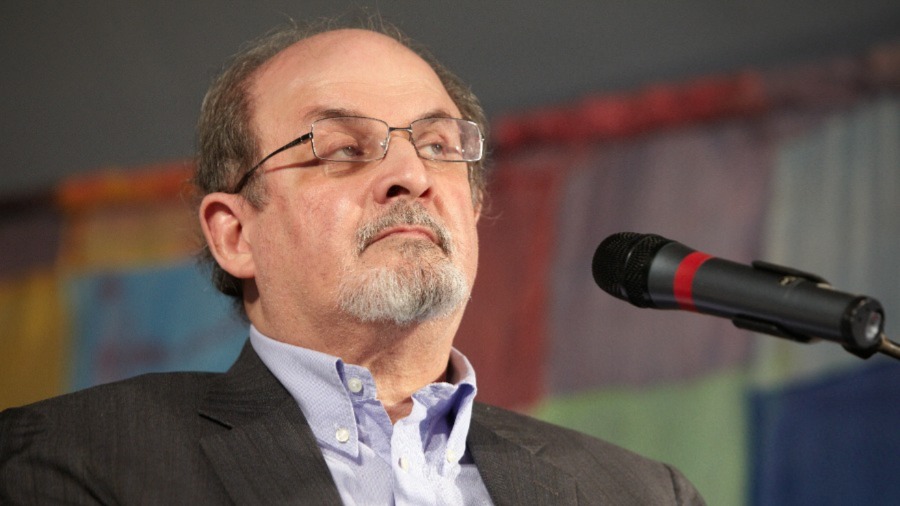

For those of us who were born in the 1970s, while the first Salman Rushdie book we read was indeed Midnight’s Children, we read it with the shadow of The Satanic Verses and the fatwa looming large. Rushdie was part literary superstar and part victim, incredibly articulate and truly the preeminent writer of his generation.

Once I had read Midnight’s Children, so impressed was I by the incredible, wondrous images stacked one upon the other, I wanted to read all I could by Rushdie. I read Haroun and the Sea of Stories with its chatty fish Goopy and Bagha and the Shah of Blah, I read Shame and a few years later, I read The Moor’s Last Sigh — looking back, the mid-1990s was when I did read a whole lot of Rushdie.

A little later, I read Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and like many others, was a little saddened that other authors had ‘done’ magic realism before Rushdie had. As it turned out, I never read The Satanic Verses; it seemed too hard to get hold of, and perhaps I simply was put off by the controversies that swirled around the book.

The last week has seen the term midnight’s children come back into our lexicon as India counts down to its platinum anniversary of Independence. I heard that a noted Indian author and academic was collating short pieces from across the globe about India, and yes, Rushdie was one of them. The author was back in the news, at least in India.

Stamina of hate

Suddenly he was in the headlines again on Friday, as images of the prone septuagenarian, felled by a man less than a third his age shocked each one of us, whether or not we had read a word written by Rushdie. Amid the horror and a sense of disbelief was the dull understanding of the stamina of hate.

Rushdie had gone from youth to his evening years, he had written a dozen books since, fatwas were revoked and even the Iran government had softened its stance on the issue. Countries had fallen, maps were redrawn and yet the hate for a book and its author remained sickeningly alive.

This was hate that remained strong, that fed on itself and was inherited by a new generation. When Rushdie gave his famous ‘Trapped Inside a Metaphor’ speech after a thousand days in hiding, his assailant was not born, his parents might have been in school at the time. This was one angry and deranged man and as a bystander said, his fury was unimaginable as he repeatedly attacked Rushdie even after he had fallen down.

It reminded me of my ‘almost hosted’ story involving Rushdie and the 2013 Kolkata Literary Meet. Deepa Mehta’s Midnight’s Children was released in February 2013 and she was to speak about the adaptation alongside Rahul Bose, who had a cameo in the film. She mentioned Rushdie was in India and would like to attend the session, ideally as a panellist or at least as an audience member. The postgraduate fan girl got the better of my festival director avatar. After all, Rushdie had spoken in Kolkata six-seven years ago, and Kolkata did accommodate divergent views.

However, once word got out, city cops and the media made it impossible for me to remain naïve. I recall a police sergeant meeting me near the Book Fair premises and explaining that it was likely that if Rushdie were to land in Kolkata, he would be sent back on the next flight. This was also communicated to Rushdie and he decided not to come. Mehta too refused to attend the festival, but the 2013 edition continued unharmed. We even had the Midnight’s Children session with just Rahul Bose, who decided to travel to the festival.

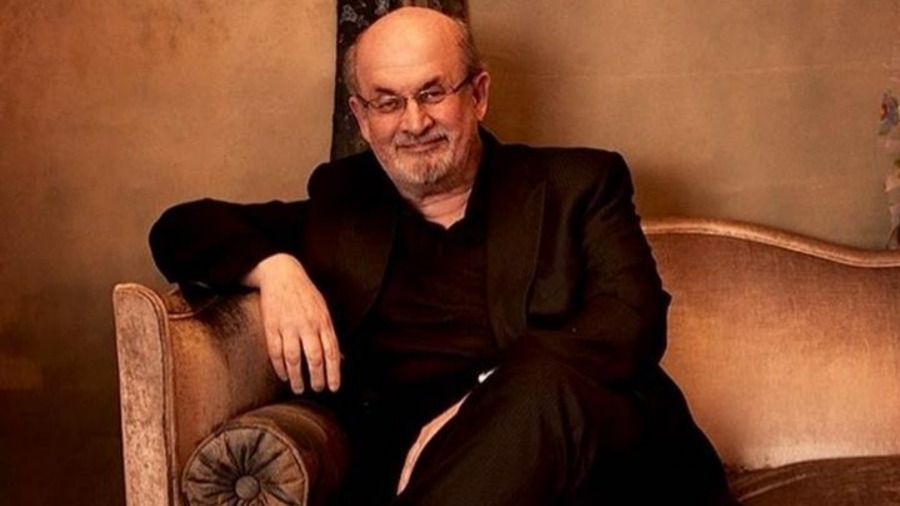

Eternal life of words

That was my ‘almost’ story of Rushdie and I never met the author or corresponded with him since then. But the reader in me continued to admire and look forward to the next Rushdie book. My admiration for the author has grown in recent years on the back of Shalimar the Clown, Luka and the Fire of Life and Joseph Anton. I also admire the fact that he managed to live a full, eventful life, with marriage, divorce, friendships, an involvement in a Bollywood film, an appearance in a U2 concert, and much else.

Today as he fights to recover from the wounds inflicted by a deluded and diabolical young man, three facts offer hope. First, I cannot recall the assailant’s name and have to google it. He will be forgotten and that is the best-case scenario for him. Secondly, at least it was not a case of gun violence that is so common in the US. And finally, and most crucially, the last 30 years saw Rushdie remain prolific and all his books will continue to be found in bookstores, online and in libraries.

That’s the thing about authors, you can harm them but you can’t kill them. Ever.

(Malavika Banerjee is the director of the annual Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet)