There are numerous Sachin Tendulkar anecdotes that have been shared and reshared over decades, so much so that they have become almost as memorable as some of the Master Blaster’s greatest knocks. From the time an adolescent Tendulkar played a prank on Sourav Ganguly by flooding the latter’s room with buckets of water to the day when a teenage Tendulkar took a power nap inside the dressing room only to stroll out into the middle at the Sydney Cricket Ground and score 148. From his love for crabs and cars to his superstitious routines to his unstinted devotion towards his cricketing gear, few gods have as many stories about them in the public domain as the God of Cricket.

And yet, there remains so much more to know about the man who batted not just for himself or his team, but for an entire nation, for two-and-a-half decades. As Tendulkar reaches 50 on the pitch of life, My Kolkata collects some never-before-heard tales about the Bharat Ratna, told by some of Tendulkar’s closest friends from Kolkata.

Practising with a tennis ball and soft hands

“It was the early 1990s and we were having an exhibition match at the Yuba Bharati Krirangan in Salt Lake. The who’s who of Indian cricket and Tollywood were present, with all arrangements made to the tee by Subhas Chakraborty (the late CPM politician). Except there was one problem. The kit bags of the players hadn’t arrived at the ground and so there was a delay in starting the game,” recalls Judhajit Mukherjee, former Bengal cricketer and presently one of the best-known coaches in the city. Mukherjee continues by describing how all the cricketers were using the unexpected break to engage in chit chat and relax. All but one, for Tendulkar was immersed in practice.

But how could Tendulkar have practised without his kit? “With a tennis ball and his bare hands,” replies Mukherjee. He goes on to add: “For Sachin, every break was an opportunity to do more, to improve. He somehow found a tennis ball and a wall against which he could smash the ball. While throwing the ball, he brought out his entire repertoire of variations, including off-spin and leg-spin. As the ball ricocheted off the wall, he played it with soft hands, quite literally. When I went and asked him about the purpose of the exercise, he told me that it improved his hand-eye coordination.”

A similar story of making the most of a break comes from Deep Dasgupta, former Indian cricketer and one of the most recognisable voices in cricket commentary today. Dasgupta takes us back to India’s tour of South Africa in 2001-02, specifically to a day that fell in the gap between the Test and the ODI series. “It was an optional practice session and Sachin asked how many of us wanted to come along. There was no doubt that he’d be going. I raised my hand and joined him. But then, it started to rain and it seemed as if the session would be called off. But not for Sachin. He simply went ahead and practised indoors. During the session, we also spent a fair amount of time chatting. Back then, he was already an icon, but he never gave that impression when he spoke. For him, no matter his greatness, every exchange was a dialogue, a conversation between equals where he’d never enforce his opinion. This meant that even though I was new to the Indian dressing room at the time, he never made me feel like I didn’t belong,” describes Dasgupta.

How Harbhajan Singh informed Kolkata about Tendulkar visiting Lake Kalibari

Tendulkar and Harbhajan Singh met a deluge of people when visiting the Lake Kalibari in Kolkata Wikimedia Commons

Ranadeep Moitra, ex-Bengal player and founder of Endorphins Corrective Exercise Studio, remembers another instance of Tendulkar from training that showcases how scientifically the owner of 100 international hundreds thought about the game. “We were training one day when I saw Sachin pick up the ball and with a simple flick of the wrist and a slight twist of the shoulder hurl it across 65 yards, right into the wicketkeeper’s gloves with a thud. I asked him how he could generate such power in his throws with so little effort. That’s when he took me aside for a masterclass,” says Moitra. Tendulkar told Moitra that “if one holds the seam of the ball at 45 degrees while throwing, the wind resistance will be so low that the ball will travel flat and fast at the target, instead of creating a looping trajectory or floating in the air”.

Away from the pitch and the game, Tendulkar always loved food, music and cars. Joydeep Mukherjee, former Bengal player, met Tendulkar every time he was in the city to play for India and is intimately acquainted with his good friend’s likes and tastes: “He loved eating mishti doi, but being an active international player, he obviously had to watch what he ate. But there’s one thing he’d always do when he came to Kolkata to play a match. He’d head down to the Lake Kalibari with me (something that also finds mention in Tendulkar’s autobiography, Playing it My Way). One such time, Harbhajan Singh accompanied us to the temple. We were driving on a Sunday winter afternoon and there weren’t too many people on the streets. When we stopped at a signal at the Rashbehari crossing, a guy on a bike recognised Harbhajan in the backseat. Bhajji impulsively told him: ‘Hume kya dekh raha hain, boss toh samne byatha hai (why are you looking at me, the boss is sitting in front)!’ In no time, we had at least 20 people tailing the car. Once we reached the temple, there were some 200 people waiting to greet Sachin. People were on top of the car and everywhere around it. It was crazy. For some time, it felt impossible to get out of there!”

‘After entering his room, Sachin would turn on the music before the lights’

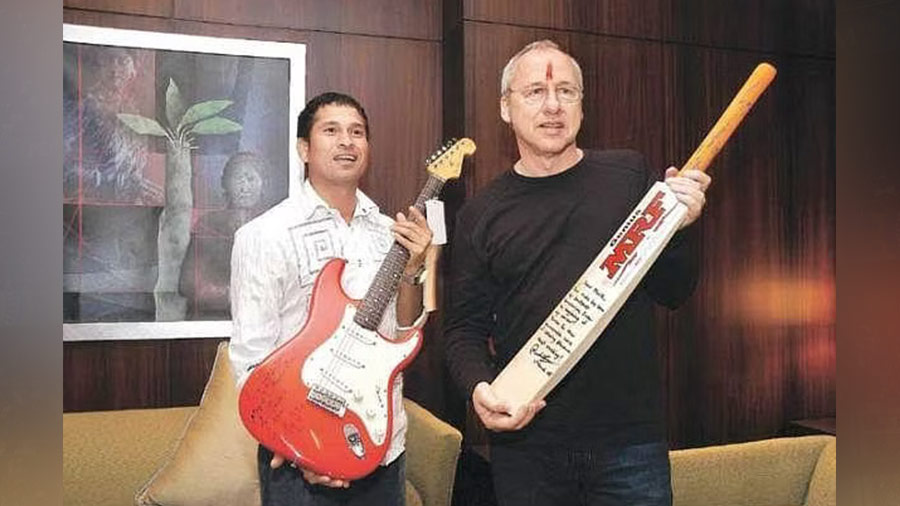

Tendulkar with one of his favourite musicians in Mark Knopfler Facebook/Sachin Tendulkar

Joydeep Mukherjee, who frequently plays golf with Tendulkar nowadays, also spoke about the time Tendulkar delivered a monologue on why motor racing, chiefly Formula One, is worth watching. “I was in his room at The Oberoi Grand in Kolkata and happened to tell him that I don’t understand the fascination with motor racing. It’s just cars going round and round. What I received in turn was a 90-minute explanation of what made F1 amazing from Tendulkar himself. By the time he finished, I was convinced!” smiles Mukherjee, who also confirms Tendulkar’s passion for music. “Sachin would carry around 30 to 40 CDs with him. After entering his room, he’d turn on the music before the lights. He was a big fan of Kishore Kumar as well as of Mark Knopfler (of Dire Straits), but he was open to listening to everything, from Indian classical to hip hop.”

Everyone My Kolkata spoke to about Tendulkar reiterated how humility was what defined the maestro, something that was not a projection of his persona but an in-built faculty. Being in touch with his roots ensured Tendulkar never saw himself as bigger than the sport. Perhaps the most powerful example of this comes from Joydeep Mukherjee: “On November 16, 2013, Tendulkar represented India for the final time (against the West Indies in Mumbai). On a day when his phone must have been on fire with endless messages and calls, he took out the time to send me a text, thanking me for my support and encouragement throughout 24 years. Even on the day his career had come to an end, he was still thinking of his friends.”