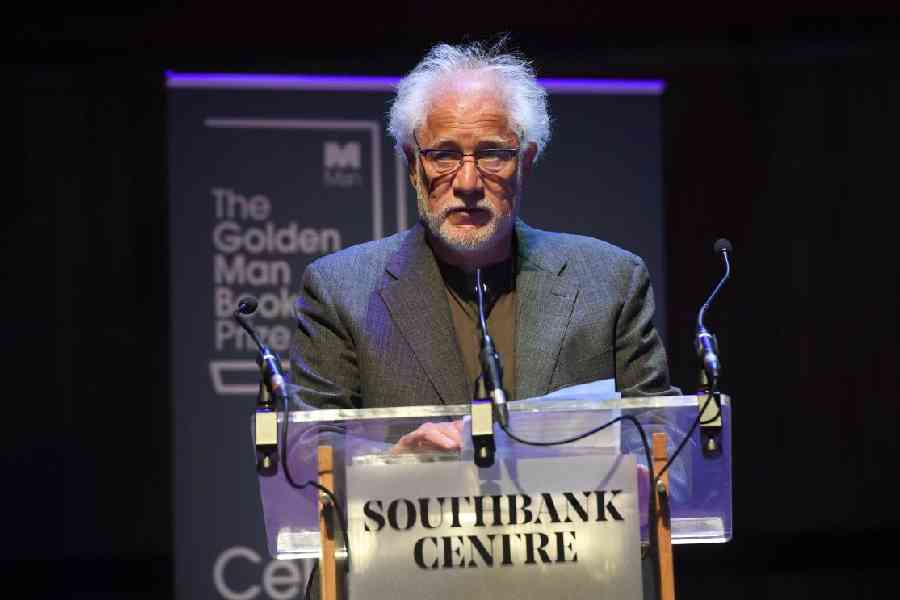

The Sri Lankan-Canadian novelist and poet Michael Ondaatje has recently published A Year of Last Things, his explosive collection of poems, after a gap of 18 years. His novel, The English Patient, most famously won the Booker Prize in 1992 and the Golden Booker in 2018, and was turned into a classic movie.

Michael Ondaatje is a steadfast Brightstar, a literary compass who breaks through separation and pain with an abiding message of hope and kindness in a fractured world. As all great poets do, with his “self-writing”, which is rooted in the lived experience, where he was separated at a very early age from his father and fatherland, Michael Ondaatje touches the wounds of those buried emotions that reside deep in the recesses of the human heart. In his most recent collection of poems, A Year of Last Things, at 81, the poet still burns bright.

The opening poem of the collection, Lock, holds the key — not only to the treasures contained in A Year of Last Things, but it offers the savvy reader the clues to the entire repertory of his career as poet and novelist. The poems read like his biography in verse, a personal memoir that moves meanderingly and endearingly. It is up to the reader to launch themself into a voyage of discovery of the poet.

In Lock, Michael seems to invoke his father, Mervyn Ondaatje, who was an absent presence in his life, and at the centre of the poet’s universe. The Canadian scholar Sam Solecki, explains: “The great hurt of everything is also at the heart of Ondaatje’s vision, though we can often narrow it down to… the breakup of his parents’ marriage, the divorce, and his subsequent childhood exile from Ceylon in 1954, an exile that also included a permanent separation from his father.”

And here is the Lock stanza that need unlocking:

Reading the lines he loves / he slips them into a pocket, / wishes to die with his clothes / full of torn-free stanzas / and the telephone numbers / of his children in far cities.

Michael Ondaatje's A Year of Last Things

In these lines, we have his father slipping the stanzas he loves, and his now-absent children’s phone numbers, into his pocket. Here’s Michael’s moving backstory. After his parents separated, his mother moved to England with his brother Christopher and sister Janet. He and his sister Gillian stayed back in Ceylon with aunts and uncles. Michael joined his mother in England at the age of 11. Michael’s mother Doris Gratiaen kept her young family afloat by working in hotels.

Ondaatje has said when he moved to England, he became preoccupied in this very new country and, in a sense, forgot about his childhood in Sri Lanka. But England was also the playground where he fell in love with jazz, often slinking away after school to dance or listen to jazz in the music bars. He immigrated to Montreal when he was 19 and received a B.A. in English from the University of Toronto in 1965 and an M.A. from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario in 1967.

In the second poem, Definition, we have Ondaatje trawling “the plotless thirteen hundred pages of a Sanskrit dictionary with its verbs for holy obsessions …,” whose “ancient phrases give you the coin of escape — that epithet for those who return to broken relationships repeatedly will row you away from confusion or remain only for remembrance.”

Any which way the reader sees it, Michael’s father is present in the “guru” or the “man” who appears in Definition:

wherever you turn / definitions push open a door / The precisely named odour of a man / who is a heart-thief

This stanza can point the reader towards the divine realm of Krishna, a revered and much-loved heart-thief, or to the Italian-Canadian thief Caravaggio in The English Patient.

In the poem, Last Things, Ondaatje writes: The air in the Piazza darkens / around Dante Aligheri / stern, high above us …

And then, in a later stanza, he writes:

I had been alone for weeks when we met there, / below Dante. The three of us lounged in a pensione, / I was writing a book about a dying man (This poem is dedicated to Connie and Leon Rooke, Florence, Spring 1990).

It appears that the “dying man” is a reference to the “English” patient (the Hungarian Count Almasy), lying on his deathbed — at a time when Ondaatje was in the process of writing The English Patient that was published two years later, in 1992.

The poem continues: Twenty years later, you were in a bed, / on Brunswick Avenue. And I kissed your feet, / Connie, one of my shy farewells.

In the next stanza, the poet brings us to the title of this collection of verse:

It was your year of last things, / but you were luminous, / within those final fires.

The poet is referring here to his friend Connie, described searingly as being “luminous” as the fire consumed her body. The covenant of grace for this book is revealed in Ondaatje’s invocation of his friend Connie for whom it was a year of last things. Connie Rooke was president of the University of Winnipeg, and president of PEN Canada.

In the deep, moving waters of his verse, in this collection, the poet journeys through the process of writing some of his own novels. The litany of his works sneaks into this collection of remembering. While in Lock, we believe “he” to be his father, in the sixth poem, Dark Garden, and in Definitions, there is “you” and there is “I”. The “he” and “you” move between different characters, but “I” is the voice of the narrator, the poet Ondaatje.

In Dark Garden, for instance, “you” denotes a young American rancher named Sallie Chisum, who steps barefoot onto a porch with Billy (yes, Billy the Kid of the Wild West) to pull a nail out of her heel. Here, Ondaatje is referring to his first book, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, published in 1970 which the poet refers to in these words: Where was I in the late sixties? / Somewhere in the middle of a book, / a western with distance violence,

But could “you” in Dark Garden not be his own mother? With Ondaatje lassoing Billy the Kid for a literary diversion.

When he was writing Billy the Kid, he was remembering his mother: So I did not hear the gasp, see her stillness, / or her unheld in that dark garden / during the collapse of everything, a marriage, / no ointment in the house, the children / unawakened, unaware

And then, he adds: Where is that unmarked calendar for 1969 / when she cleaned the blood off the mat floor. / A single mother in those missed years, with only the small glimmer of possibility or luck still years away from us.

The “single mother?” Could she not be his mother, Doris?

In the poem What Can Be Named In The Earth, the poet turns to his novel Anil’s Ghost, set during the Sri Lankan civil war, where he narrates the massive human rights tragedy whose details are preserved at the Nadesan Centre for Human Rights. He writes: Only at the Nadesan Centre / are there dated political maps / with named mass graves / the thousand illegal burials.

Michael Ondaatje in his youth at the University of Toronto

In this poem, he takes us into the Muthurajawela wetlands of Sri Lanka, and then to a zoological museum in Colombo, but he finds nothing: All data avoids the naming of cities, / rivers, ancient harbours.

And it is only in the Nadesan Centre that he finds the evidence of a human rights catastrophe.

In the poem One Hundred Views of The Pettah Market, Ondaatje takes us back to his growing-up novel, The Cat’s Table, with a reference to a mynah bird, to a pre-teen Michael who is nicknamed mynah in the novel: A narrow lane with dentists crouching in sunlight, / lady barbers, book repairers, sarong tailors. / Along the post office wall a gathering of mynahs / in their youth being trained to sing, the way / you transmit knowledge to a descendant.

And, in the earlier poem, What Can Be Named In The Earth, the poet writes: of how tailorbirds, hill mynahs, / bill-clatterers, the drongo / alter their plumage and calls / when migrating north.

Like the “hill mynah” altering its plumage, when Ondaatje migrated on the ship Oronsay from Colombo to England, he too might have altered his plumage and speech as the adolescent Michael grew during the voyage.

It is delightful to find the poet adopting a multi-genre, mongrelized style — of both short poems and longer tracts of poetic verse — that represents a postmodern/postcolonial worldview.

Other characters from The Cat’s Table appear in the prose-poem Winchester House. We meet Father Barnabas, Michael’s junior school master, and Cassius (one of Michael’s friends on the voyage, Ramadhin being the second friend). Cassius “loathed him [Barnabas] for the habitual beatings that still returned as a poisonous dream”.

In Winchester House, the poet reflects on his childhood friend, Skanda, whose name he uses for a character in Anil’s Ghost, pointing out that “the real Skanda would appear more fully as another doctor — Gamini, the book’s central male character”. The poet again works the personal history of his novels into this book of verse.

Ondaatje reveals nuggets of childhood years at his school, Winchester House: “…the dragon who governed the boarding school was a Father Barnabas, and no one who survived that time would ever forget his name, or forgive him a half century later.”

“He had come disguised into our childhood world wearing the dark cassock of a priest, his large body belted with a Christian cord of rope. He probably thrashed every boy numerous times in the two or three years they would be under his academic and supposed spiritual care.”

“Those were the years when we learned to protect ourselves by becoming liars, being devious, never confessing to a crime, in fact confessing to nothing, good or bad. Such as pouring petrol and setting fire to the rhododendron bush in the small garden belonging to Father Barnabas—right beside his window as if the light from it could witness his crimes.”

Father Barnabas exists both in the fictional world of The Cat’s Table — and in his own real world. Of course, the real Barnabas was not on the ship with Michael. Ondaatje informs us in the prose-poem Winchester House that he and his schoolmates tracked his career to discover him “living in the last years of his life, with a small dog in a one-room apartment on South Bridge Road in Singapore, where he could be visited by a former student who, having located his address, partially strangled him with the rope and then cut his throat with a rusty knife so he fell back over a kitchen table and expired there.”

Obviously, Ondaatje’s prose-poem is ambiguous, floating between fiction and fact. A few pages after the above (fictitious or imaginary) passage of the attack on Barnabas, we learn that a friend of Ondaatje’s, an archaeologist named Senake Bandaranayake, travelled to Singapore for a conference, where received a phone call from the former teacher. It was Barnabas inviting him to stay with him, but Senake was reluctant, remembering those ferocious beatings. But he still went. They talked late into the night. Ondaatje writes: “And then Senake slept on the sofa until, in the middle of the night, he awakened to crying. The old man weeping. Senake got up, walked into Barnabas’s bedroom and saw the old priest beating the dog.”

Julie and Harish Mehta are the co-editors of the book Between Homelands in Michael Ondaatje’s Fiction, being published by Routledge in October 2024. The co-editors have taught at Canadian universities for several years.