His opening line never varied. Every time he saw me or spoke to me on the phone, he’d exhort, “Anoothi, kyon roothi!” (Why is Anoothi miffed!) and chuckle. That was his standard greeting, always -- till much later when his progressing illness after a stroke gradually confined his work and connections fell by the wayside.

Much before that, when he was still very much a presence in the Indian food scene, he had started greeting me in this unique way, perhaps in response to the harsh reviews I would often land up writing in The Indian Express, where I did a restaurant review column from 2000-2001. Or, it may have been after he felt a little miffed with something else I had written. I can’t remember that now -- it is irrelevant.

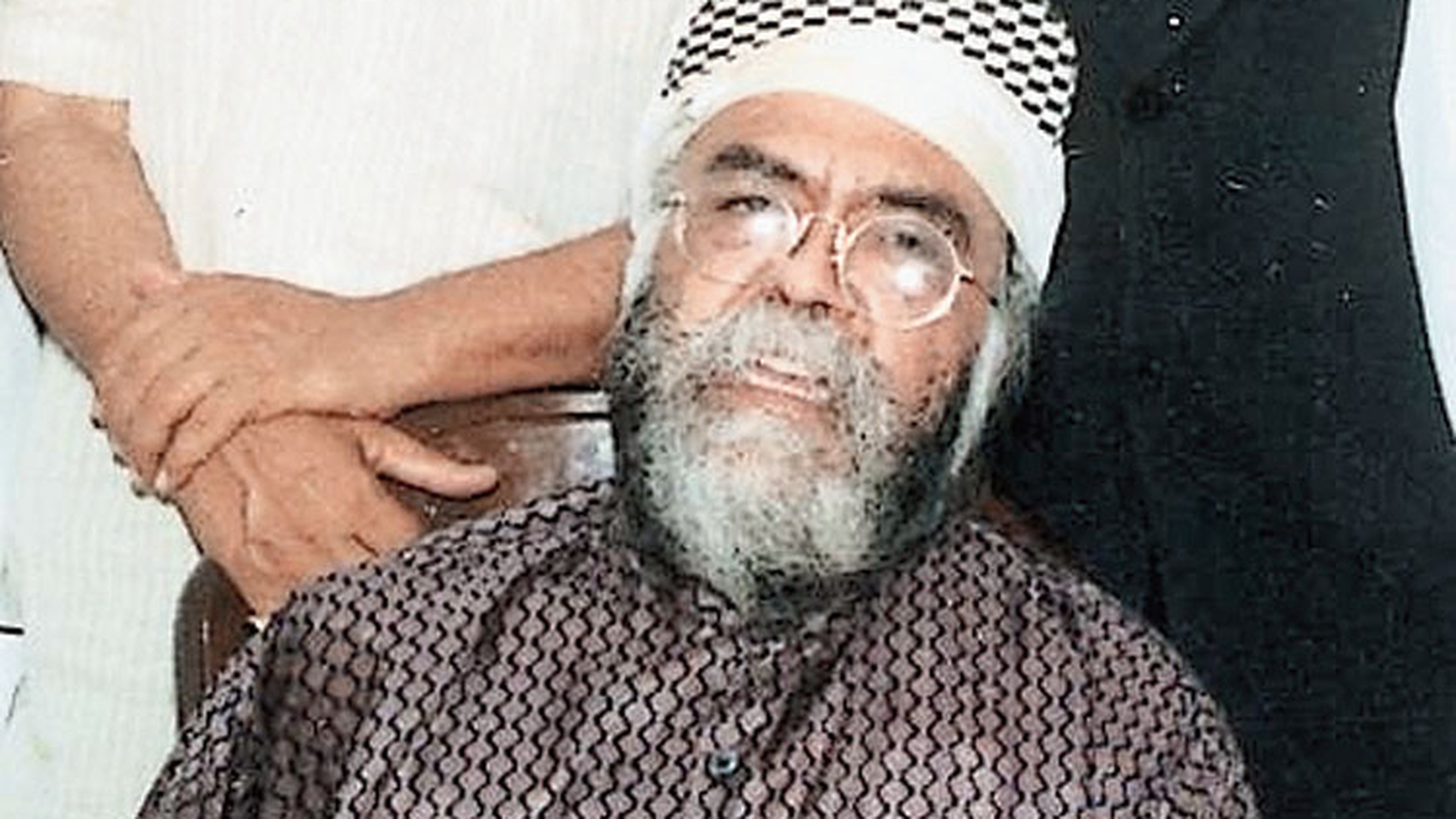

What is important are those early memories of Jiggs Kalra: always full of life, spirited, always wanting to engage with young talent as he saw it and to cultivate it. He was an impresario and an influencer before the terms got fashionable, a man of knowledge, good taste, of a formidable reputation and impeccable media relations.

When the Agra Summit happened in mid 2001 between Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Pervez Musharaff, I was still just one year into my food writing profession. Kalra had been assigned to cater to the big banquet and he had devised an impressive menu—with ingredients from Lucknow, gourmet pearls in the biryani and if memory serves me right, elegantly-named dishes such as “daure ki tafreeh” (fun on the tour) which was a dish of prawns—seafood also famously preferred by the most gourmet PM India has ever had, Vajpayee.

I got an exclusive on this story despite my newbie journalistic status. Marut Sikka, who used to work with Kalra, came down to our newspaper office in Qutab Institutional Area, fortuitously close to Kalra’s house in Pushpanjali Enclave, and gave me details of the grand meal. It was a big byline. The thing about Kalra and many other stalwarts who shaped Indian gastronomy and restaurant food in those years, pre social media and pre the Internet, was how much they were interested in knowledge, in diving deep into culinary traditions of the country and presenting these to a wide audience. Any one, who was similarly enthused had their attention and respect, I suspect.

I continued to engage with Jiggs till at least 2007, when he got Meat Beliram cooked for me at his home—for another column. This was a famous recipe from Prashad, his definitive cookbook, which he had got from the legendary Madan Lal Jaiswal, founder chef of the restaurant Bukhara. Naturally, it was a treat for me.

Prashad: Cooking with Indian Masters (Allied) was published in 1986. It is a testimony to Jiggs Kalra’s deep research that it is still one of the most solid works on Indian gastronomy that few have been able to match. It has been on the curriculum of most catering colleges for several years now but most of Kalra’s subsequent books are equally well researched and offer a wealth of knowledge about the country’s regional cuisines. I have his books on Awadh, Punjab and Rajasthan and refer to all of these regularly. Kalra, of course, was famous for turning the concept of andaz in Indian cooking on its head—and for measuring every pinch of turmeric or spice and recording the precise measures.

When he turned to restaurant consulting, he was as exacting. After his early successes with Bukhara and Dumpukht, where he had been brought in by then ITC Hotels supremo Habib Rehman, himself a gourmet par excellence (yesterday, lamenting the loss of a friend, Rehman showed me an annotation by Kalra on a book where Kalra had written out an affectionate message to Rehman, his “mentor”), Kalra’s reputation was so solid and fierce that chefs felt intimidated. But the excellence of the restaurants that he worked on was always borne out by the food—whether it was the Great Kebab Factory, which still exists as an unparalleled brand, Singh Sahib at the then Park Royale (now, The Eros New Delhi), where Kalra served food from the undivided Punjab, or Dehli Ka Aangan at the Hyatt Regency. In fact, Kalra also consulted for Sadanand Maiya-owned MTR Foods. His influence was all pervasive and much before the advent for social media influencers, Kalra was the original, dabbling in all aspects of Indian food retail.

I last had a meal with him, I think, at Punjab Grill, then a joint venture between Wrapster Foods owned by him and son Zorawar and Amit Burman’s LiteBite Foods. The first outlet had come up in Delhi’s new mall Select Citywalk. On the menu were many of the classic dishes that one recognised from Kalra’s research—the taste of bhatti da murgh cannot be forgotten still. It would mark a new journey for his research and restaurant ownership for his family and him. Zorawar had then recently come back from studying in the US and was ready to build a business based on his legacy. The father and son sold their stake in the business to LiteBite in 2012 but by then the seeds of a bigger business were sown.

In 2014, when I took a bite of the galauti kebab burger at the then newly opened Farzi Café in Gurugram (the first of the chain, owned by Zorawar Kalra’s new company Massive Restaurants), which presented modern Indian food, I immediately recognised it for what it was—a chip off the old block, never mind the new presentation. The flavours were spot on—as they obviously would be given their pedigree.

The past lives on in our present, and so it was here too.

Anoothi Vishal is an author, food columnist, researcher and curator.