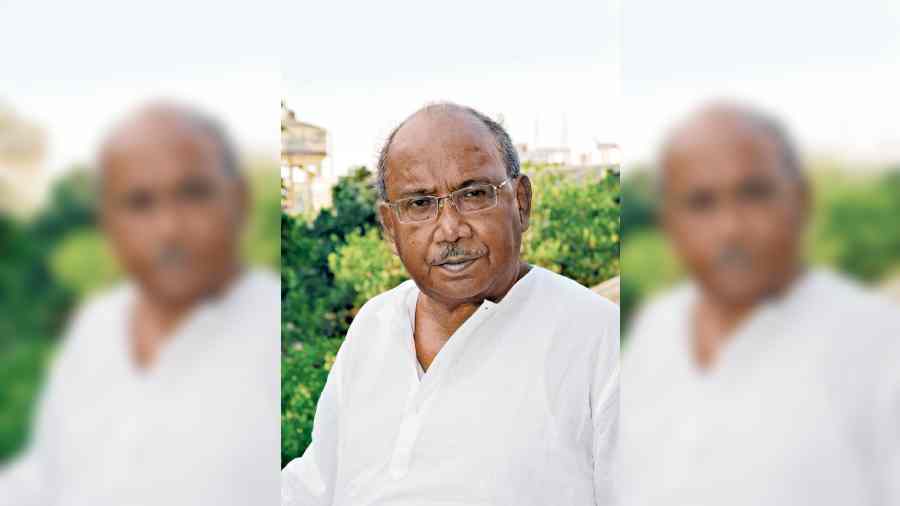

This soft and gentle ‘cut’, characterised by the persona of Tanubabu as he was fondly called, marks the end of a long and deeply unforgettable ‘scene’ — one that leaves behind long shadows of a lost era, a populist culture and an artistic expression based on humanism, generosity of soul and celebration of simple emotions.

Allowing things to be, without manipulation or fabrication for the sake of adding thrills or frills for engaging the audience, or finding joy and peace in the small things of life was a philosophy that echoed with the spirit of the times and also appeared to be wonderfully real and, at the same time, quite satisfying for the generation. In keeping it simple, it implied an exploration of life without intellectually explaining the traits, character, or psyche, but rather accepting them as they are with a sense of empathy and tolerance.

In Bengali cinema, Tarun Majumdar represented the last vestige of an age of classicism that originated in its golden era in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The focus was on specific elements of storytelling, often originating from literature, as the most effective and captivating way to engage an audience.

The plot was neatly contained to a simple and conventional structure of a beginning, middle, and definitive ending that did not leave the audience disillusioned or frustrated. Often, the conflict resolution was entangled with two goals: one romantic and the other social or familial. Eventually, these conflicts merged, and the romantic interest became involved in the larger conflict.

With his first film, Chaoa Paoa (1959), in which Tarun Majumdar teamed up with Dilip Mukherjee and Sachin Mukherjee as team ‘Yatrik’, he developed a distinct preference for exploring the psyche of wanderers and bohemians who run away from home and embark on adventures, from sublime to ridiculous, and eventually discover love in the strangest places.

An eternal vagabond or someone uprooted from family and home is a universal prototype that recurs throughout his filmography, from Basanta, who escapes driven by inherent wanderlust in Palatak (1963), another film he collaborated in as ‘Yatrik’, to Rasiklal, the young notorious brat who fantasised about becoming Prithviraj Chauhan in Shriman Prithviraj (1973), or Kedar in Dadar Kirti (1980), where a dim-witted simpleton is banished by his father to his uncle’s house in Hazaribagh, Bihar for failing to pass his B.A. exams thrice.

Koel Mallick and Rituparna Sengupta on the sets of Chander Bari

A moment from Bhalobasha Bhalobasha

A moment from Amargeeti

Many of Majumdar’s best-loved films — from Balika Bodhu (1967) to Bhalobasha Bhalobasha (1985) — explore this desire for human warmth and empathy outside the family and the longing for acceptance among strangers. A noteworthy feature of Majumdar’s script was the exploration of the typically amusing quirks and idiosyncrasies of ‘Bangaliana’ from different social strata, particularly from the town or village areas of Bengal, leading to some unforgettable comic sequences performed to the hilt by some of his favourite actors, including Anup Kumar, Utpal Dutt and Robi Ghosh. Among the other highlights of his films were the songs, thanks to a lifelong association with Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, perhaps one of the longest film-maker-and-composer collaboration in the history of Bengali cinema.

It is to them that we owe some of the most memorable songs spanning four decades — Jibonpurer pathik re bhai (Palatak), Amaar dukhe dukhe janam gelo (Nimantran), Haridaaser Bulbulbhaja (Shriman Prithwiraj), Tomar daake sara dite (Dadar Kirti) — the list is endless, not to mention some of the most cherished Tagore numbers, some of which have become more or less synonymous with some classic scenes from Majumdar’s films.

As Indian parallel cinema was consolidating its roots around the mid-seventies of the last century amidst a major socio-political turmoil, there came two Tarun Majumdar films that stand distinctly apart in his filmography — Sansar Seemantey (1975) and Ganadevata (1978). In the former, Aghor is a petty thief desperately wanting to settle down with Rajani, a prostitute he loves passionately. But destiny stands in their way.

In the choice of story that centred around a dark world of depravity, vengeance and violence and a strikingly realistic portrayal of the red-light area with the characters being raw and real — it was indeed a striking departure from his earlier body of work.

Sansar Seemantey investigated Tarun Majumdar’s deep knowledge of the economic and socio-political repercussions of his time, and the physical and psychological aspects of marginalised life in a thriving metropolis.

Filmed largely on location, it breathes a sense of deep authenticity with its unobtrusive cinematography and compelling sound design.

A few years later, he took up yet another challenge with Ganadevata, a story about a village caught in the whirlwinds of change before the Second World War, through the interactions and conflicts between various social archetypes.

Based on a famous novel by Tarashankar Bandopadhyay, it has the rebellious blacksmith Aniruddha and the much respected Debu Pandit question the system for its injustices and prejudices.

The film unravels a slice of a typical Bengal village caught in the throes of change. Along with the vivid portrayal of hate, vengeance, and revenge in rural life, Ganadevata also depicts sensuality and eroticism quite unabashedly. As the sexual politics and exploitation prevalent in feudal rural society are depicted in all its grime, so too is Aniruddha and Durga’s relationship, purely based on physical attraction.

As a film-maker who carved his own signature in an era of Ray-Sen-Ghatak-Sinha, he perpetually pursued creative expression based on moral values, humanism, and the spirit to fight the adversities of life with boundless optimism.

For so many generations of audiences, Tarun Majumdar stands out as one of the most admired film-makers of their time. This is because of his remarkable ability to imbue a sense of admiration and appreciation for simplicity, good taste and sensibility. That is where, Tanubabu would stand unique and universal, forever.

Film-maker Atanu Ghosh