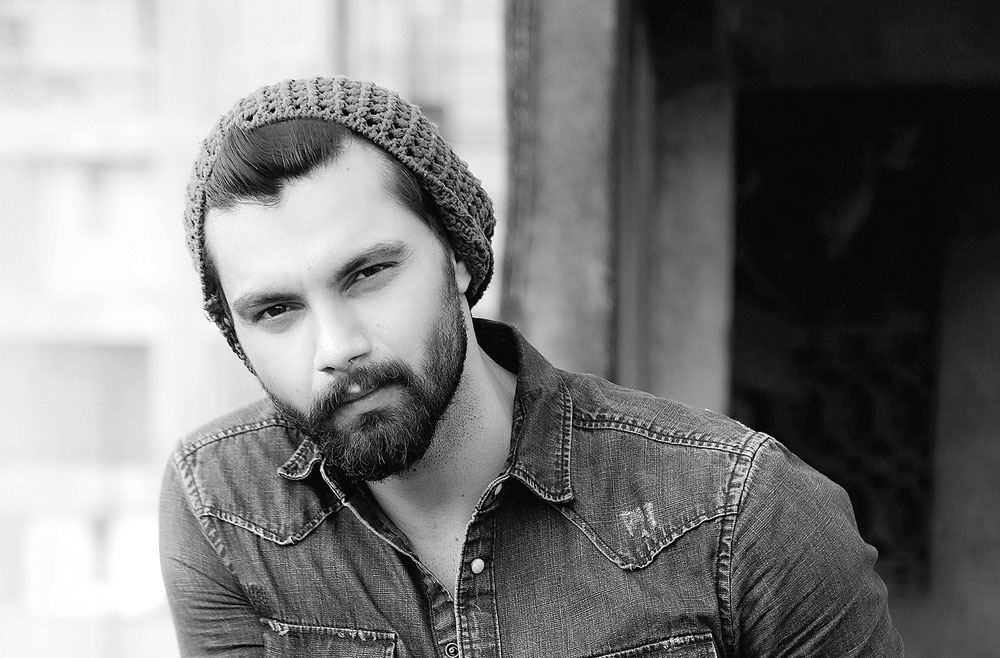

When you meet Nick Rampal for the first time, you are a little surprised. He is a tall, handsome man in his 30s, with a smiling face, a booming voice and an excellent profile. He is also dishevelled and scruffy, and he has not bothered to iron his clothes or shave.

As he walks into a mall restaurant, his voice carries across the floor. He can pass off as a business professional or a sportsperson even on a careless day off. He certainly does not look like a leading model. But that is what he is.

Nick is, in fact, one of the best-known models of Calcutta. He had modelled for the very mall where the restaurant is located. You vaguely recall his images in the advertisements for the mall and try to match them with the man sitting in front of you.

But then Nick Rampal is not Nick Rampal, in more than one way.

When told that he does not look like his pictures at all, Nick smiles. “Why should I look like a model always? When I am working, I am dressed like a model. But it’s not only that,” he says. If he does not speak in the measured tone of showbiz people, he does not display their groomed reticence either; he does not stop talking. He lowers his voice. “When I am modelling, I am transformed. I change myself.”

Modelling is not just wearing clothes, he says. “Actually, it’s not about clothes at all. I don’t care if the clothes are good or bad. It is all about attitude. It’s how I look in the picture. That is modelling,” he says passionately. “But that’s when I am working. Otherwise I am a different person. People don’t recognise me in my building,” he says. He lives in a gated community in Tollygunge. “I like to hang out with others in the building premises. When I chat with others, I don’t want to be recognised as a model or anything,” he says, in a rough mix of English and Bengali.

He can also go unrecognised because in Calcutta opportunities for modelling are limited. Models are not very familiar faces. Nick has been in the business for 10 years. He still feels he has a long way to go.

And yet he has arrived somewhere. He has certainly travelled a long distance from Bikrampur, a small, impoverished village in Bengal’s Bankura district, where he was born. Homes in his village did not have electricity till very recently. As a child, Nick went to a pathshala because there was no school. He says, “And we were taught English only from Class VI.”

When he says he will not behave like a model when he is not working, he says it with a pride, even arrogance. He will not only not disown his roots; he will display them. He will not forget himself to blend into the glamour world. He is who he is. Then again, he is not. So blatantly that it almost does not matter. Was he born to a Bengali family? Rampal is an unusual surname for a Bengali. Nick pauses for a while. “Nick Rampal is not my real name,” he says. “My real name is Falguni Patra.”

Falguni arrived in Calcutta in 2003, after his school-leaving exams. His family supported him, but they could not afford much. He joined Vidyasagar Evening College. Nick had big dreams: of doing something larger than life, of becoming larger than life, shimmering with stardust, touched with tinsel. He knew he had the height and the physique to enter the world of glamour. He would find out that he had another very important quality: the ability to grit his teeth and go on, never mind what others were saying, never mind the humiliation and rejection.

Rejection, in particular, was good, he would find. Rejection would spur him on.

After about two years in the city, when he was living in tiny shared rooms, and college and studies were steadily receding into the background, he entered a “glam hunt”. He did not even make it to the top 30. It hurt him. Determined, he entered the Gladrags Mr India contest and was among the top three in the eastern zone. “I went to Delhi,” says Nick.

Around that time, encouraged by a cousin, he changed his name from Falguni Patra to Nick Rampal. Nick from Nick Arora, a character played by Saif Ali Khan in the 2005 Yash Raj production, Salaam Namaste, one of the biggest grossers of that year. In the film, Nick Arora is a young, cool Indian who goes to Melbourne to make it big and meets Preity Zinta, another Indian in Melbourne with the same aspirations. Rampal is from Arjun Rampal, one of the few model-turned-actors who could make some mark in Bollywood. He says, “They would laugh at my name, ‘Falguni’. Said it sounded like a girl’s name. It was very difficult for me, entering this world.”

The new name was a good handle; a good entry point into modelling as he did odd jobs, including selling clothes, for a living. Often, he would face the prospect of having no roof over his head. He would go hungry. He would sleep in friends’ houses, or make living arrangements in exchange for work. He has been out there. “I have seen everything,” says Nick.

He did not give up. Something in him — his doggedness especially — attracts people. His directness too. He can go up and talk to anybody. Nick caught the attention of choreographer and model co-ordinator Ashish Banerjee. Banerjee groomed Nick for the ramp and gave him confidence and affection. Banerjee would pass away soon after Nick met him. A loss Nick is yet to get over.

By this time, he had begun to get noticed. He began to get calls for big-ticket events and well-known designers. Calcutta designer Abhishek Dutta, he remembers gratefully, featured him at Kolkata Fashion Week in 2009. Debarun, another city designer, took him to the next level by featuring him at the 2011 Lakme India Fashion Week. Nick would also participate in the 2015 Lakme Indian Fashion Week wearing the designs of Shantanu and Nikhil and Arjun Khanna. He would be seen in Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s clothes as well.

Now he is the face of several brands, especially those from the city. He drives a Ford and is very proud that last Pujas an advertisement hoarding featuring him was up someplace adjoining his village. But it is still not easy. Modelling pays little and this is one world in which women do better than men. So Nick, when he is not a model, works hard at shoot direction, getting other models and often even modelling in campaigns that he is directing. He calls himself a fashion curator and travels extensively.

According to him, models are discriminated against within the modelling community, which privileges celebrities over them. “Why are sport stars and actors featured in advertisements? It means models get even less work. And why are models not named,” he asks angrily. He continues, “Leading designers, when they feature actors, obviously name the actors. But even if they are featuring the topmost models, they are never named. Why?”

At a shoot, Nick assumes another persona. He is in a commanding position, hollering at younger models on how to stand, how to sit, how to hold a pose, a look. When exasperated, he shouts that they ought to give up modelling. “You have to be very committed. You have to be disciplined. And you must have attitude,” he says. His dream is to be a mentor to Calcutta’s models and introduce them to international circuits.

“A model must know how to look like a mannequin,” he says again. He has just featured in and co-ordinated the Rina Dhaka show at Fort William. The model should look like a mannequin, or better, turn into an image. He can, he says. And he does. Of course, editing helps too. In the images, in billboards or newspapers, Nick looks like he has ironed out not only the crumpled ends of his clothes and his bulges, but also his personality. He is at one with the sharp suit he is wearing, proudly.

But shedding the personality is more difficult than shedding fat: it all comes back the moment Nick steps out of the ramp. Back in his own clothes, Nick looks less ironed again. And he is fine.

There is no conflict between Nick Rampal and Falguni Patra. If Nick Rampal is shooting, Falguni is hovering over and Nick does not mind. The two are friends. Sometimes Nick wistfully dreams of opening a small biryani restaurant — or would that be Falguni?