Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

— The Second Coming,

W.B. Yeats

One hundred and four years ago, William Butler Yeats, Paul Lynch’s countryman, was lamenting the lacerated body of Ireland that was limping back to life after the horrors of World War I. Lynch seems to have seamlessly taken the baton from Yeats and is running the current lap, when Ireland is still breaking into riots after more than one hundred years of falling apart in Yeats’s worldview.

It seems like just yesterday that the world received the news of another novel about gory deaths, the other world and the brutality of civil war in Sri Lanka, Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka, the 2022 Booker awardee.

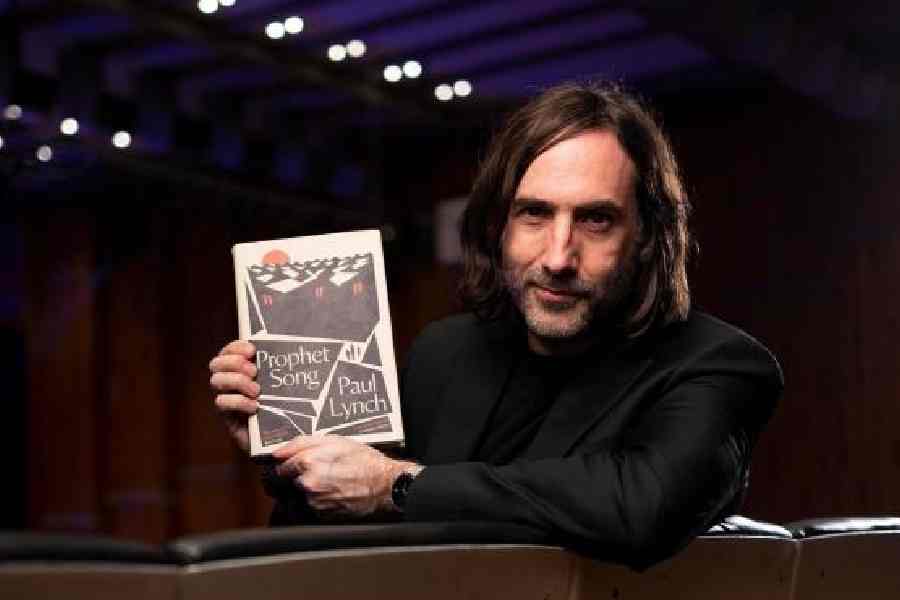

Lynch, 46, who lives in Dublin but was born in Limerick, comes from a literary background. His father taught English literature and his mother Irish literature, and he was always encouraged by his father to write. A voracious reader, Lynch is loved and respected by his family, friends and fans because of his fidelity to his wife Sarah and his affection for his children. With his shoulder-length hair and aquiline nose, and a slight Irish drawl, he could pass off as a pirate or rock guitarist or arm candy on date night.

He was presented with his Booker trophy by last year’s winner Shehan Karunatilaka at a ceremony held at Old Billingsgate, London. He is the fifth Irish author to win the award, worth £50,000 (€57,563), according to the Booker Prize, following Iris Murdoch, John Banville, Roddy Doyle and Anne Enright.

The event had a keynote speech delivered by Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who was released from prison in Iran last year and spoke about how empowering it was for her to have read Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale that was banned in Iran.

The Booker committee might not have been unanimous in the selection of the 2023 winner, but the subject of war and loss, grief and dystopia clinched it for Lynch. Lynch’s keen empathy and compassion for the complete destruction of any sense of empowerment of citizens by a megalomaniac state that would take shape in the near future, is the engine driving the story.

In his trenchant yet heart-touching Booker Prize acceptance speech, Lynch admitted it was not an easy book to write. Quoting the Apocryphal Gospel, he reminded the Booker audience that, “If you use what is within you, what is within you will save you. If you do not use what is within you, what is within you will destroy you.”

He also admitted that: “The rational part of me believed that I was dooming my career by making this move. But I had to write this book.” He acknowledged his children, Emily and Eliot, and their contribution to his project by thanking them for “opening our eyes” to the plight of “the innocence in the world”.

Last year, Lynch was diagnosed with kidney cancer, from which he has now fully recovered. “The diagnosis which was shattering was my knock at the door,” he says.

Canadian novelist Esi Edugyan, chairwoman of the 2023 judges and a previous Booker-shortlisted author, called the tale “a triumph of emotional storytelling, bracing and brave”. Add to that his burgeoning list of awards with each of his novels and it is not hard to hear the music in his prose. The lyrical novelist is best read aloud in parts. Innovative use of the audial makes him first among equals.

The plot delivers a sledgehammer punch with its sheer simplicity: A perfectly happy family is broken apart when the father is imprisoned by the secret police and his wife, the mother of four, has to struggle to keep the family alive.

One of the most inventive stylistic skills that Lynch has brought to bear on this novel is the lack of paragraphs. I would decipher this formalism as a strong message of oppression by an unrelenting state on its citizenry, barring them from even taking a breath. Or being completely corralled in a single pen of over 300 pages with a fence around them. This is a meta-metaphor.

The novel’s ingenuity also lies in the way its creator invites the abjectness of refugees, migrants and escapees from bloody homelands to incur monumental losses of broken families, dysfunctional lives and perpetual terror into the telling. Very often the enormity of crimes against humanity gets hidden by the ruling majority. Lynch puts an enormously virulent spin on this old idea of marginalisation and fragmentation of the minority and totalitarianism.

As the reader rides through the gripping narrative that gradually mesmerises at times and saddens at others, there is a universal pulsation here of the right-wing stretching out and touching any nation it wishes. And though the novel is technically set in Ireland, the story could be anywhere in the world, when one considers the idea of right-wing domination and fear under irrevocable state power. In that way, Lynch has given us a novel of globalisation.

Lynch has lyrically woven a futuristic story of a tyrannical government that has put its citizens under surveillance, making them fearful and suspicious. Readers will find it a tale of dystopian nightmare, a story that shows how near we have come to the edge. Lynch conjures images of fear and resistance as our countries turn into a living hell.

His debut novel, Red Sky in Morning, was inspired by a TV documentary about the excavation of Duffy’s Cut, a site near Philadelphia where, in the 1830s, Irish emigrants, mainly from Ulster, were discovered in an unmarked mass grave. It explores themes of emigration, racism and brutality.

His fourth novel, Beyond the Sea (2019), was inspired by a true event and is an existential tale involving two castaways on a boat in the Pacific Ocean. The novel has been compared to the tales by Herman Melville, Fyodor Dostoevsky, William Golding, Samuel Beckett and by the novelist’s own admission, he was inspired by Herman Hesse. Beyond the Sea won several awards including France’s Prix Gens de Mers in 2022.

A powerful presence in Prophet Song is the sea. The last paragraph of the novel highlights the sea in the consciousness of Lynch, and undergirds the sheer power of the ocean in the past, present and future as envisioned by many Irish playwrights, poets and novelists. In Irish playwright J.M. Synge’s majestic play Riders to the Sea, a riveting image is the sorrow expressed in the keening or quiet weeping of the womenfolk whose husbands have drowned at sea while fulfilling their professional commitments as fisherfolk.

In Prophet Song, in Lynch’s imagination the sea becomes the place to go to, with a suggestion of more assured survival, because, as the protagonist states unequivocally, the sea is life. Quietly powerful with the electric heraldry of the desire to live, Eilish, the mother of four children (one of them her teenaged daughter Molly), looks a prophet in every way.

“She looks for Molly’s eyes but cannot find the right words. There are no words now for what she wants to say and she looks towards the sky, seeing only darkness, knowing she has been one with this darkness and to stay would be to remain in this dark. When she wants for them to live. And she touches her son’s head and she takes Molly’s hands and she squeezes them as though saying she will never let go, and she says to the sea we must go to the sea, the sea is life.”

There is a song running in his prose that touches his readers. In the epigraph to Prophet Song Lynch takes a few lines from the heart-wrenching theatre of Bertolt Brecht: “In the dark times / will there also be singing? / Yes, there will also be singing. / About the dark times.”

“What informs this book is the sense of liberal democratic slide that’s been ongoing around the world for the past six, eight years, perhaps 10 years? It was the sense of unravelling that so many of us have just been tuning into and feeling anxious about the thought that could this happen here. No, it couldn’t but yet, there are so many countries around the world where they thought the very same thing,” says Lynch.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life, and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College