I met Aparna Sen while making Kadambari. I used to go to their place to meet Konkona (Sensharma; actress and Aparna’s daughter) for our preparations and there I met her first. To be honest, I was in awe of her. She is a lady that I look up to, not only because of her legendary status as a film-maker and an actress but most importantly as a human being. It was during the shooting of Basu Paribaar that she told me one day, “You always have these addas with Soumitra (Chatterjee), why don’t you have it with me?” I responded, “How can I just call up ‘Aparna Sen’ and tell her that I am coming over for a drink and an adda with you?” She said, “Why not?” Little did she realise that I will take her up on that pretty seriously and even sometimes dictate the menu that I yearn to have for dinner.

Ever since, she has become a dear friend and I so look forward to chatting with her over so many topics. Since quite some time, she had invited me to her abode in Santiniketan but this summer I could finally go there. The general air of quietude was so lovely and there was an openness in the surroundings which made her reflect on her life. Excerpts from our adda:

Let me go back to your childhood. Where did you grow up?

I was born in Calcutta, at my home. My second sister was born at home while my third sister was born in a nursing home. I grew up in Calcutta, the place I relate to the most, the place I love the most, the place I hate the most.

Why hate?

Calcutta has a lot of problems that I don’t like, I wish the weather were different. I remember coming out from a shooting floor and Manik Kaka (Satyajit Ray) was also coming out from the shooting of Jana Aranya. He said, “Ki re kemon achhish?” I replied: “Fine, but it is very hot”. “Gorom kaale gorom porbena?” he had asked. At that time the studios were not air-conditioned. I wish we had weather like Kenya, where it is perpetually 24. The garbage disposal is much better now. Traffic is much better now. The eccentricity of Calcutta has gone.

Aparna and Suman in Santiniketan. Pabitra Das

What do you mean by eccentricity?

My city can wring happiness from the utmost poverty. You have these makeshift households under bridges. I saw little children sitting there, I saw a woman making dal, another one throwing a child up in the air and laughing... I thought people were able to eke happiness out of this. Once I had gone to the Park Street cemetery. It had rained before and we were walking through wet grass. I saw a wonderful sight. The sun had come out from behind the clouds. There was a patch of water around. Poor, raggedy-looking boys from the neighbourhood were playing football with gusto. There was life in the middle of a cemetery. I was completely overwhelmed. It brought tears to my eyes.

Do you reflect and think back on the influence your parents had on you? I want to stress on your mother (Supriya). Your father, Chidananda Dasgupta, was a famous scholar, everyone knows about him.

I was their first child, born at an early age. My father once told me when I was four, “You are an independent individual... You can do whatever you wish with your life.” I asked? “Really? Then I am not going to school from tomorrow”! Then my mother said, “This is the problem. Why are you doing this?” Baba said: “If you don’t go to school, how will you earn a living?” I said: “I’ll mop the floor like Kali Didi.” Ma started crying. I could not bear it, I was sensitive. I said, “No, no, no. I’ll go to school.”

Much later, after I became a film-maker, when one of my films was being shown, Baba went up on stage, and said: “I’m just the producer of the director!” This is true in more senses than one. Both my parents influenced my childhood. My mother, who was a homemaker, had a beautiful aesthetic sense. Once in a while she worked, she did social work. She worked in an advertising agency for a while. My parents used to consult each other a lot. My mother had this wonderful idea of aesthetics. She could arrange flowers beautifully. She had not learnt ikebana but she would arrange them naturally like that. When we were very young, and did not have resources, Ma cut up old saris and made curtains. They had cane bookshelfs... they could not afford wooden ones. There was this tamar kosha, and inside there were these pins and she used to arrange flowers in that. It was very tasteful and humble. I think I got my aesthetic sense from my mother. But often she would give in to Baba. When I asked Baba about God, he would say: “How can I tell you about something which I don’t know myself.” He was an agnostic. My parents lived a life in the arts. They loved music concerts and dances. Many people came to their home... artists and writers.

Pabitra Das

How is Jibananada Das related to you? Do you have memories of him coming to your house?

He is my mother’s first cousin. Yes, I do have memories of him coming to our house. He didn’t talk to us. He talked to my father. We used to call him Minu Mama, and Labanya Mamima, his wife. They used to come and Baba and Ma used to call him Borda. He was quite eccentric. He would say to my father, “You and Supriya leave this house and let me live here! You live in my house.” He would say it with complete earnestness. They used to take us to see Shanta Rao’s dance. I was a child of eight and I would get to see Mohiniattam. It was so beautiful that I remember crying. As a pre-teen we had a lot of exposure to art.

Konkona had told me that you didn’t allow her to watch Hindi movies...

Konkona didn’t see mainstream movies and the elder one, Kamalini, didn’t listen to me. She would sneak out with her friends. She was a bit of a rebel.

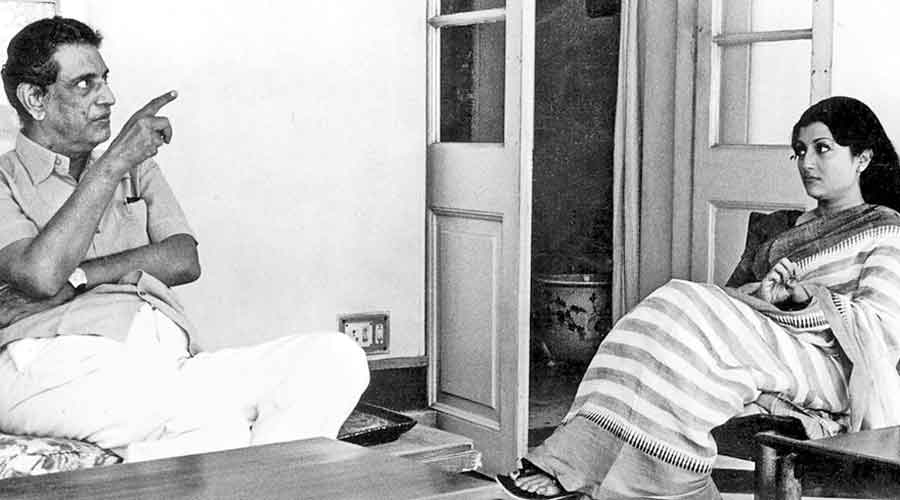

Satyajit Ray and Aparna Sen. The Telegraph

Why was that? Knowing you, you would want to have your daughters exposed to all kinds of art forms. Then they can make a choice. It seemed, from Konkona, that there was an embargo of sorts.

I wanted Konkona to watch good films from different countries so that her taste would be formed. It is like comparing children growing up in a classical musician’s home. They listen to songs from the outside but at home they listen to their parents doing riyaaz.They automatically know the notes and pitch. Their ear for music develops. With Konkona, a taste for good cinema developed at an early age. We would come here (the house in Santiniketan), Baba would get his video cassettes. And we would have a week of Antonioni or Fellini. I remember Konkona crying her heart out after watching Dead Poet’s Society. I asked her the reason and she said it is so beautiful. Her taste was formed. After that, she watched mainstream films. Of course, now mainstream films have become really interesting. Now we don’t have formula fare. I wouldn’t have given up acting if I had Konkona’s choices of films to act in.

Soumitra Chatterjee and Aparna Sen. The Telegraph

You had said that you didn’t enjoy acting in most of your movies, hence you had a preference for doing comedy.

Because I did not have to do nyakamo, being forcefully coy or cute. I was expected to be coy and raise my eyes, smile, look shy and all of that. Comedies did not have that. It had a much more robust kind of feeling. I enjoyed doing comedies. And if I had to be coy in comedy, I could do it with a certain bit of tongue-in-cheek.

But you have acted in films by Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen. Why didn’t the craft of acting interest you?

Most of the time I wasn’t doing their films. In order to keep the home fires burning... I wasn’t lucky with my marriages, I had to bring up the girls on my own... I had to put food on the table, so I used to act in mainstream cinema.

But it is difficult for me to imagine you doing something for so long that you don’t love intrinsically... you did it for 20 years or so.

It is easy. I was a thoroughbred professional. Whenever I made a film I made sure that I gave my best. We did not have stylists then. I would buy the saris, I introduced hair dressing. People were angry with me because I brought a hair dresser to the set. You can’t change your appearance if you don’t change your hairstyle.

By mid-1980s, I had given up acting. We were poor at that point of time. One day I observed my elder daughter doing Santashi

Ma-r Puja so that the family income would increase. I was shocked. We didn’t have money to repair the TV then. I realised that I had to earn. I started doing mainstream theatre then. I enjoyed bringing in Utpalda’s (Dutt) traditions into it...

Was joining mainstream theatre out of compulsion?

I did theatre right through. I was doing theatre when I joined films. I was doing Baksho Bodol and Professor Mumlock with Utpalda simultaneously. Theatre came early in my life. Even in school I did theatre. I got prizes for my dramatic abilities. My ambition was to become an actor then. I told my parents the same thing. They wanted to send me to RADA in London. When I was about 13, they said I could act in Utpal Dutt’s plays as soon as I finish school.

Later we walked out of Utpalda’s group and we started a group of our own, Calcutta People’s Art Theatre. We did some plays there but at one point we realised the way they were doing things, I didn’t like it. Nothing that is amateur can really be powerful. Because the money is not there. Of course the group theatre movement is really important. I felt that if I have to earn money, I can’t keep doing this. So I only acted in films. When I decided that I would do commercial theatre, I made sure that it would be a hit.

What did theatre teach you as a director?

Theatre of course teaches you voice projection, grace of movement, how to take the light, where to stand, to see whether your co-actor is also getting the light. These things are at the back of your head while you are acting. That is a technicality which films have also taught me. I can’t dismiss my career as an actor in films because it has taught me many things. Because I was an actor for so long I can understand if my actors are facing any difficulties in the execution of what they are doing. If they are having a problem with motivation, I can very quickly tell them how.... When writing dialogues, I know I can deliver this kind of dialogue. I can write dialogue which the actors can deliver easily.

When did you think that you’d become a film-maker? Was it always on your mind or did the idea come to you later as the years went by?

In the mid-1970s I was doing a Hindi film. I was sitting in the make-up room and waiting. Then I thought to myself, the kind of films I am doing here... I don’t believe in them. Do I have to keep doing this for the rest of my life? That was a very frightening thought. Then I thought of doing something else by myself. I was good at writing and decided to write a short story. I wanted to write about something that I really knew inside out. Then the idea for a story on an Anglo-Indian lady came to me. We used to have a principal called Violet Clark who used to stay in a hotel, The New Kenilworth. Often we would go there, and I knew she lived there. Alone. Somehow all this started something inside me, which I cannot define. The short story turned out to be longer and longer, it was becoming more about images. I was describing them. And once I even wrote a dissolve (an act or instance of moving gradually from one image or scene in a film to another). Then I figured it was turning out to be a script. I knew it wanted to be a screenplay and I let it be a screenplay. I would research about Anglo-Indians with a friend. While I was shooting for James Ivory’s Hullabaloo Over Georgie and Bonnie’s Pictures in Jodhpur, that’s when I started writing actually. Miss Stoneham became a real character for me. She would often dictate what I wrote.

In the first two decades of your film-making, your films were mostly women-oriented and also about human relationships. But none of them were political films. Mr and Mrs Iyer had a political backdrop. And Ghawre Baire Aaj was an out and out political film. Did you realise this change that happened in you in the last few years or politics in films never interested you before?

The world is changing around you at such a fast pace, everything that we knew has been reversed. Somewhere we are faced with the threat of India becoming a Hindu state. All that disturbs you... one is bound to change with the changing circumstances. I can no longer make a film like 36 Chowringhee Lane because the world was a much more innocent place then. Think of security issues now. With Ghawre Baire Aaj I was making a film based on Tagore’s novel (Ghawre Baire). Politics plays a big part there. That was the politics of pre-Independent India. Now with Ghawre Baire Aaj, the politics was today’s. It became political in nature. For Yuganta the political inspiration came from the Gulf War, the oil spill.

Would you consider yourself to be feminist?

I do, to some extent. But I don’t want to be labelled a feminist. I am not one. Some feminists feel everything about men is wrong, they are competing with men. Trying to be better than them. There is an aggressiveness about it. I consider my feminism to be a part of my communism. I feel equally concerned about trafficking of children or the issue of migrant labourers. Women have suffered for so long. That concerns me deeply. I know many men who are concerned about it. When I am called a feminist, I can show you many films were it is not only about women’s emancipation. Films by Satyajit Ray and Rituparno Ghosh have also talked a lot about feminism. I wrote about it once, called the ‘Female Gaze’. It is different from the male gaze but it doesn’t have to be a woman who has a female gaze. You, as a true artiste, is, to some extent, androgynous. You have to understand the male and female point of view. I have had gentle, nurturing men in my films.

For example, Soumitra Chatterjee’s character in Paromitar Ekdin.

Yes. He was gentle and sensitive.

What is your politics? Would you call yourself a Left Liberal? Or a Leftist? Where do you stand in the political spectrum?

I think of myself as a Left Liberal. Now I find very little of true Left left. Everything is Right or more Right. My politics is entirely issue based not party based.

Isn’t issue-based politics sort of an escapist politics?

It is a practical agenda. Our fault is that the civil society doesn’t engage enough with politics. We need to engage more. You can vote for a party which is a lesser evil, most of the time in a democracy you vote for the least corrupt. If I were asked, would you vote for a party that would want to turn India into a Hindu state, I would say no. I would rather vote for the doorpost. I feel issue-based protest has a tremendously important place in politics, in society and in our lives. Civil society has the responsibility and duty of raising their voice whenever something happens that is not desirable.

Ultimately political parties should pick those up and translate them into action. I often feel there is a gap there.

Because the civil society does not protest enough. The Left ideology is the most noble ideology that anybody can think of. It is deeply inspiring. However, when the Left comes into power it is the same as any other party. What the Left can do and has the duty to do is to get themselves together and form a strong opposition, which can check capitalist excesses.

Intellectual is a bad word these days. This negative perception of the intellectual, do you feel it is solely an artefact of the propaganda machine? Or do you feel some intellectuals have stopped engaging with the real issue?

I agree with that. The intellectuals should have engaged more. In the meantime, the anger of the common people was growing. Not only in India, in the US too. When a party came to power where you found less of the Left intellectuals, celebration of mediocrity became something you could engage in. Earlier on, you at least looked up to people like Rabindranath, Amartya Sen. Then came a time when Nehru was a bad word. There is a perception that intellectuals don’t understand the real world. What is the real world? The intellectuals who are much maligned today have always shown the path to a better way of living. Whatever they may be. If they are silenced then you are going for a mediocre world. And if you are happy with that I have nothing to say.

Lastly, some of your colleagues, slightly older than you, passed away, like Soumitra Chatterjee, Nabaneeta Dev Sen and Shankha Ghosh. You have grown up with them, worked with them. How do these deaths affect you personally?

I was not close to Nabaneetadi, but I felt very bad because she was a gutsy woman. She would say come and fight, come and fight to death, to cancer... it is really admirable apart from the fact that she wrote such wonderful poems. I felt very sad when that happened. She was very young at heart and she was too young to go. With Shankhada it was a passing of an era. Shankhada was like the North Star that showed us the direction. A meeting got a certain gravitas if Shankhada was there. Shankhada was someone we looked up to. He had given Kalyan and me a lot of affection. We would never be able to sit in that house, in that book-lined house ever again. There is nobody left except the daughters. With Soumitra, I felt kind of devastated.

I remember you called me at 2 o’ clock at night…

I called you because you were so close to him. I felt everything was coming to an end. I still haven’t come to terms with Soumitra’s passing.

Do you think about death?

I used to, I was terrified... now I don’t think about it much. I am a reasonably healthy person. I have good genes. Death will come when it will. The only thing that scares me is pain. When I’m not there, I’m not there. What do I care?! It doesn’t give me a sense of my own mortality, not any more.