If you have never been in love with Bruce, now is the time.

Chances are you might yet catch a whiff of his transient genius before he disappears again. The next time a special year like this comes, some of us may not be around. Like Bruce Lee himself.

Tough, wiry Bruce. Boyish charm and killer eyes. Supremely fit. What a con the Fates played on him. So possessive were they about him, that they denied him a fling with chivalrous old age. Why else would they whisk him away so gloriously young?

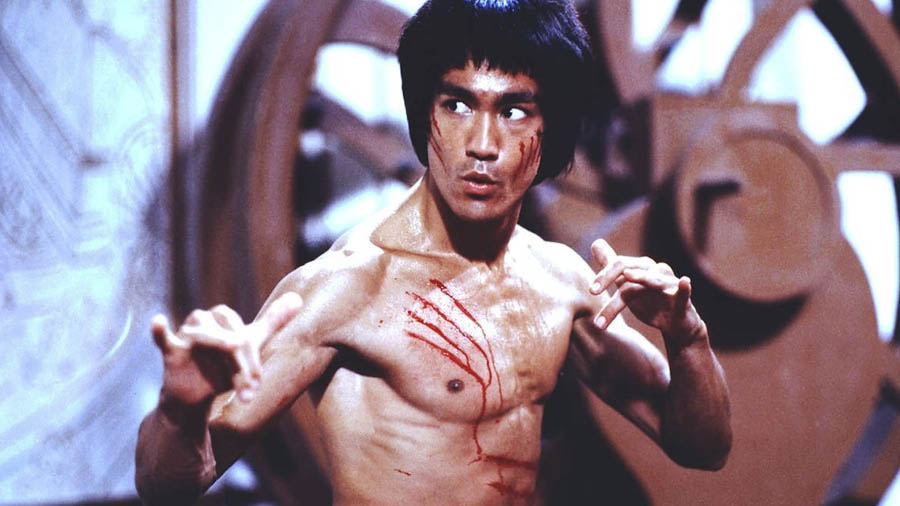

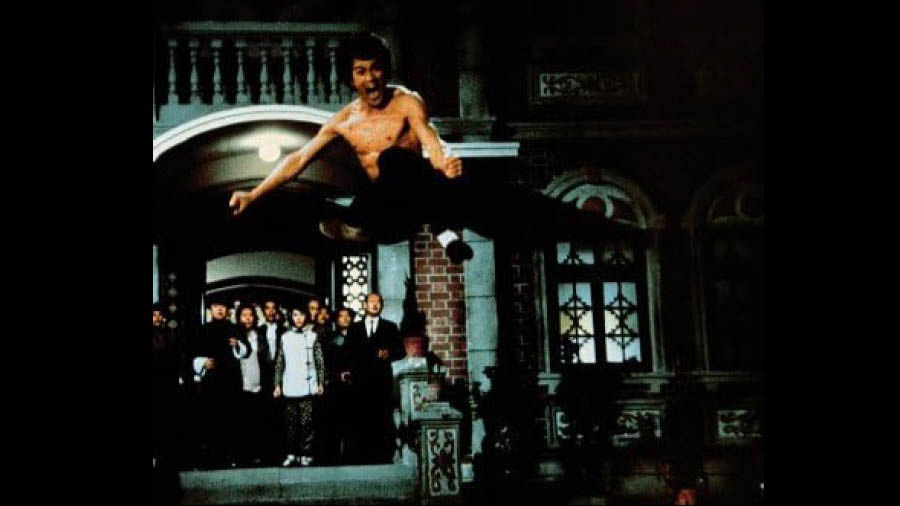

Another scene from 'Enter The Dragon' Youtube

There’s surely a counter-argument to such romantic notions about heroes dying young but that’s a topic for another day. For now, let’s rewind to that unforgettable summer when Bruce still dwelt on the edge of disbelief. The summer of Enter The Dragon, as it turned out, when Bruce the ‘Little Dragon’ checked in forever. How he did that is there on YouTube, and it’s a fascinating watch.

This is a clip from that film. Also in the frame is a big, brawny character called O’Hara, half a foot taller, but it’s the smaller guy all eyes are on. The two square off; fingers splayed, wrist against wrist, knees bent. Then it’s suddenly over.

End of fictional contest — the big fellow was no match — but what the audience had just witnessed was authentic Bruce: speed, precision and an easy swagger no camera could have faked.

Bruce himself sums it up best. “A good fight should be like a small play, but played seriously,” his character says in the film. In his case, the “seriously” also becomes entrancingly so. That was in August 1973 — the high point of Hollywood’s belated embrace of Bruce’s star power in a milieu that not very long back would stereotype Asian men as docile, emasculated or villainous.

For those not familiar with Enter The Dragon, the film was Bruce’s first and last in a lead role in a venture where an American studio was also involved. Bruce plays the role of Lee, a martial artist, who infiltrates a martial arts tournament to bust a drug ring. The fictional Lee eventually takes on the main villain, Han, in a riveting final act that unfolds in a hall of mirrors, easily the film’s most iconic scene.

Hint of the legend

At its basic, Enter The Dragon is a martial arts film with breathtaking fight scenes; a movie for the ages, if you are a Bruce fan. For those who aren’t, it is such scenes that sum up the film: a Bruce Lee show, and not much else. But it is around these scenes that a hint of Bruce the legend also unravels — especially his hybrid, combat philosophy of style as ‘no-style’. The lethal flying kicks, legs airborne in a ballet of balance and momentum, and the explosive one-inch punch he perfected were the visible extensions of that philosophy. But more than anything else, Bruce made you believe that what he did on screen he could do all that in real life too. With the same exquisite precision.

“Lee was lightning fast, very agile” and his confidence was “dazzling”, fellow martial artist and sparring partner Chuck Norris would tell Black Belt magazine.

Yet Bruce was not built like the typical action hero. He was a little over 5’7” and weighed 64 kilos. But there was something about him, paradoxical yet irresistibly fascinating, and an intensity that made it impossible to look away. Those who did, even for a moment, would invariably miss the action because Bruce existed between moments, in the split second between intent and execution.

The impact on moviegoers in America was telling. Forget the racist stereotypes; here was an actor from Hong Kong — though born in San Francisco’s Chinese Hospital — who had emerged as a superhero; infinitely alluring and irrepressibly dominant. Then he was gone, as suddenly as he had burst upon the world, a fabled fighter with a sinewy physique and balletic grace, leaving behind him captivating glimpses into what the human body was capable of.

The big-screen recognition from Hollywood that Bruce long wanted had finally arrived, along with global stardom, but it had come too late to do him any practical good.

Bruce was dead by the time he came on screen in Enter The Dragon. He died on July 20, 1973, in circumstances that were mysterious. Bruce had complained of a headache, popped a pill and decided to take a nap but never woke up. The cause of death was officially listed as swelling of the brain following an allergic reaction to a painkiller — an unspectacular exit for someone who seemed spectacularly immune in his chiselled invulnerability. He was only 32 when he died, six days before the film’s Hong Kong release and a month before it would be screened in theatres in America. July 2023 thus marks half a century of the film and also of Bruce’s death.

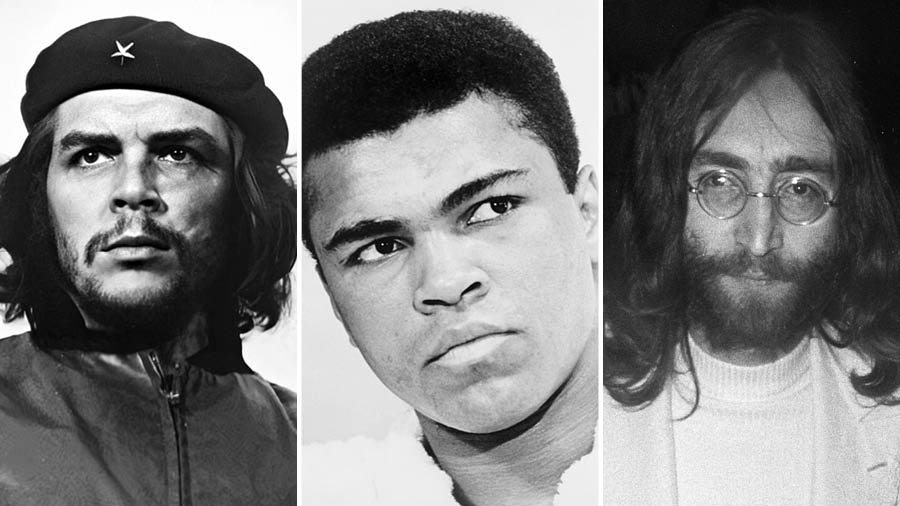

(L-R) Che Guevara, Muhammad Ali and John Lennon Wikimedia Commons

But Bruce wouldn’t be denied fully. If he had to transit into the other world, it would be at the height of glory: from star of the illusory screen to afterlife immortality; universal in his appeal and instantly recognisable; as recognisable as Che Guevara, John Lennon and Muhammad Ali — some of the icons who captured the popular imagination in that heady era of anti-imperialism and counterculture. What the world of ephemeral success had withheld from Bruce, death would grant.

Vicarious redemption

By the time the film ended, Bruce had a whole generation of fans hooked. Transformed into instant devotees, they would go back home and do a hundred push-ups as part of a daily regimen, hoping to recreate their bodies in the mould of their sinewy idol. Again and again they would turn up at movie halls, from scrawny teens to sundry underdogs, just to watch Bruce take down guys bigger than him. It would be a sort of vicarious redemption.

It hardly mattered to these fans they would never be able to replicate Bruce’s rhythm, the way his feet teased in and out of reach, or the blur of his lightning fists. For them Bruce epitomised self-belief; someone who had redefined the template for masculinity and also shown that one’s body, even if relatively small and slender, could be turned into a weapon, trained to endure and if needed hit back with devastating impact. That was one of the reasons the box-office success of Enter The Dragon would lead to a world-wide interest in kung fu and other forms of Oriental martial arts; apart from the obvious aesthetics of toned elasticity.

Thwarted on the cusp of cinematic consummation, Bruce had morphed from a martial artist into a metaphor. An extraordinarily inspirational figure, important in different ways to different people. That’s why he is still so relevant, even years after his death.

Remember this quote, one of the many the Web throws up when you type Bruce Lee’s sayings? “There are no limits… only plateaus, and… you must go beyond them.”

Can Bruce be called the greatest martial artist ever? Maybe yes. Perhaps not. Doesn’t matter, really; he was certainly the most beautiful to watch.

There were, of course, those who claimed Bruce was brash, obsessed with his body and rather vain. But what his critics saw as brash and vain, his fans adored. Enamoured of Bruce, they would pin his posters on bedroom walls from where he would hold unconditional sway, hypnotic in his fluid muscularity and forever young.

Bruce’s passing was indisputably un-Bruce Lee-like but by then he had done enough to intrigue his fans, including those who would come later. He intrigued another category of fans too — the one that dug into Bruce’s worldview to find out what the man was like behind the legend. It appears that Bruce the man was similar to Bruce the idea.

‘It hits all by itself’

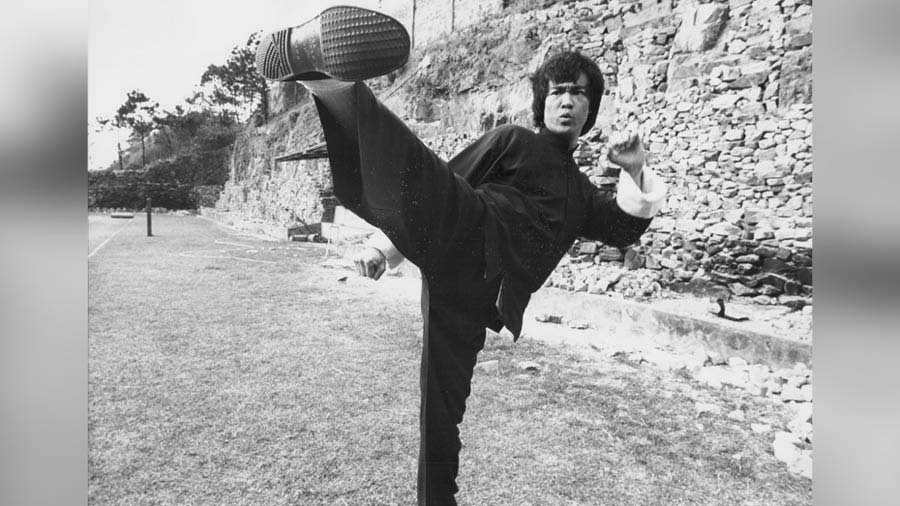

Bruce Lee in action IMDB

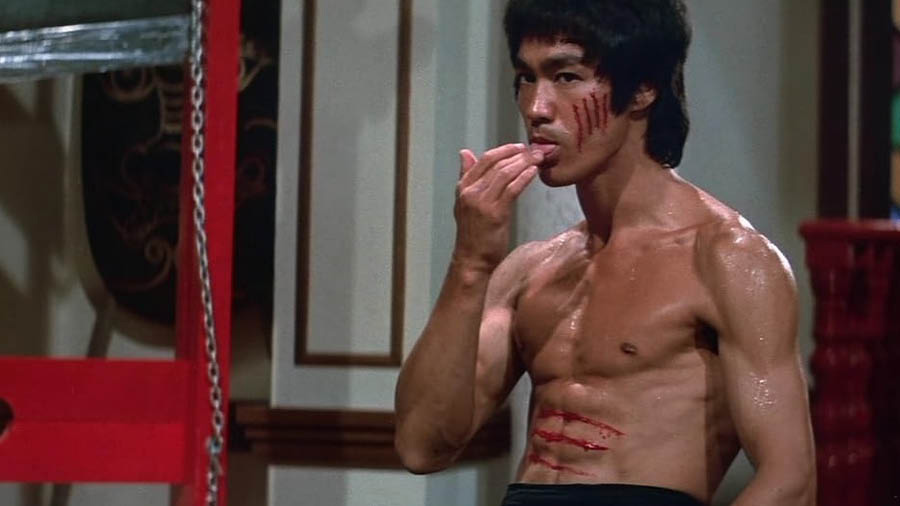

A suggestion of Bruce’s combat philosophy comes early in Enter The Dragon when Lee the character talks to his teacher.

Teacher: What is the highest technique you hope to achieve?

Lee: To have no technique.

Teacher: What are your thoughts when facing an opponent?

Lee: There is no opponent.

Teacher: And why is that?

Lee: Because the word ‘I’ does not exist.

“I do not hit,” the fictional Lee goes on, holding up his fist. “It hits all by itself.”

What he effectively does here is rid action of all superfluous intention, lifting it to a level of purity where violence becomes almost like poetry.

‘Be water, my friend’

Bruce Lee in the 'Fist of Fury'

In real life, Bruce would reconfigure differences in the various forms of traditional martial arts to arrive at his own flexible system that he called Jeet Kune Do — or the way of the intercepting fist. Absorb what is useful, he would exhort. “Learn the principles, abide by the principles, and then dissolve the principles,” he says in Bruce Lee: Artist of Life, a collection of his philosophical musings, poems, notes and essays.

Somewhere along the way, between his days as an aggressive teen in Hong Kong and his evolution as a martial artist, Bruce had become a thinker, too.

“My life...,” Bruce would tell an interviewer, according to the book, “seems to me to be a life of self-examination, a peeling of my self bit by bit, day by day.” It was Bruce’s form of self-education, essential to seeing through situations.

Let’s go back again to Lee’s conversation with his teacher at the film’s beginning. “The enemy has only images and illusions…,” the teacher tells Lee. “Destroy the image and you will break the enemy.”

The same words recur towards the end — in the form of Lee’s silent reminiscence inside the hall of mirrors — before he begins smashing the mirrors inside Han’s exotic museum. Han’s multiple images fall away as the glass begins to shatter, reducing his advantage of ambush by delusion. Mind over situation, mind over illusion of situation. Get the drift?

How could any fighter succeed against an opponent so cerebral! A man who had entered the labyrinths of his mind and re-emerged “devoid of set patterns”.

Be like water, Bruce would advise. “Empty your mind, be formless, shapeless — like water…. Be water, my friend.” Water, Bruce would say, could penetrate the hardest of substances. It could take any shape and was never hurt no matter how hard it was hit.

At its basic, it was a call to adaptability, not only in sport — combat or otherwise — but in life, too, in a world riven by seemingly unbridgeable chasms and crystallised differences.

Yet the irony is hard to miss. The enduring appeal of Bruce’s real-life art today rests mainly on an illusion, the cinema screen. For once, though, there isn’t any difference. Bruce the actor and Bruce the martial artist were essentially the same — in the immaculate precision of their art.

If you have never been in love with Bruce, now is your chance.