“Amma then spent decades on the fringe, a renegade lobbing hand grenades at the establishment that excluded her

until the mainstream began to absorb what was once radical and she found herself hopeful of joining it”

That was Bernardine Evaristo in a moment of unknowing self-fulfilling prophesy as her eighth book Girl, Woman, Other won the Booker Prize 2019 (jointly with Margaret Atwood), making her the first Black woman in the award’s history.

Now 61 years old, Evaristo’s first book was published when she was 34. The author was a theatre student at the Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance, London, and later went on to launch her own theatre company with extensive ideas for people of colour. She is now a professor of creative writing at Brunel University, London, and vice-chair of the Royal Society of Literature.

The narratives of Evaristo and her character Amma align as the book begins with a radical Amma landing a gig at the National (Theatre London). Tracing the life of 12 distinctly different Black women whose narratives, lived experiences and lineage are more than often subtly interconnected, Evaristo’s book is a mellifluous series of opportunities — to understand, learn, observe and grow.

Speaking to The Telegraph over the phone one fine Wednesday evening, Bernardine Evaristo deep-dived into reserving judgements as a writer and questions of privilege.

Evaristo started writing when she was at drama school. Having grown up in the suburbs of London in a mixed-racial family of eight, books soon became a window to the outside world. Born to a Nigerian father and an English mother, she remembers her surroundings being a “very white area” and using reading as an escape.

“I began reading as soon as I could. I couldn’t afford too many books, so I was initially a big library visitor which later became second-hand bookshops, as I got older. Books were my main form of entertainment, other than youth theatre, and books brought the world into my little life, to be honest, expanded my imagination, intellect and vocabulary,” said the author.

This love for books naturally turned its course towards writing when she was majoring in plays and every student of theatre was encouraged to write their own. What started as poetry at 19, continued throughout the 20s and was eventually published as Island of Abraham (1994).

“ageing is nothing to be ashamed of

especially when the entire human race is in it together”

In the book, Amma and her break into the National is celebrated and vilified by various characters as the author contemplates the concept of age, which is a recurring thought in her mind as well for having won the Booker at a point in life that she considers ‘late’. It lends an air of surrealism to the entire event.

“People often break through when they are much younger, especially writers, by their first or second book. Even Hilary Mantel, when she won the Booker for Wolf Hall, was probably 10 years younger than I am I think — a middle-aged woman, but still younger. For this to happen to me at such an age is a phenomenal experience and one that I am incredibly grateful for. I am just enjoying it and taking every opportunity that comes my way, because I value it so much.”

Writing, experimenting and creating for the self, her ideas have a purpose but never a defined audience. “It (the Booker prize) has opened my writing up to the world. Not just this country, but the world and, as a writer, you want the world to read what you are writing. We want our writings to be read at a macro scale and winning the prize has done just that for me,” she adds.

There are 12 characters in Girl, Woman, Other that you grow to love, hate or form indifferent opinions about. Evaristo had famously said that she had wanted 100 characters to be in this book but stopped at 12! Was there ever a thought of expanding upon any of the characters in a longer format or the oft-experienced ominous feeling among artists for possibly putting ‘too many eggs in the same basket’?

“I feel that I have gone into the lives of my characters in as much depth as I wanted to. Even though they have 30 pages each, you still get a strong sense of who they are and the purpose of the novel was to explore womanhood through as many characters as possible rather than to dig deeper and be more comprehensive in each individual storyline. As a writer, I have so many more stories to tell and they will not be about these women,” she adds.

A poignant tale in its own right, Girl, Woman, Other reads like an observational piece sans any judgement. There is disassociation in documentation without compromising on the depth of emotions. “Yes, yes! That is a really good observation because that is what I do as a writer. I reserve my judgements because my job is to bring them alive in the most interesting and humane way possible. That means that they are their own creations and they must not be suppressed by my opinions,” she agrees.

Not imposing your personal politics on your characters is something she teaches her students of creative writing. The idea is to create a complex, complete, flawed individual who will have many sides to them.

“Maybe some of their behaviour is unpalatable to you or that you don’t morally agree with it, but that doesn’t mean you should pre-judge it because if you do you will only end up with two-dimensional characters. In a way, you are going to force-feed the character to your readers with your judgements. And what the reader wants to do is make up their own mind. So, definitely, when I am writing all my books, I am allowing them to be who they are. Of course, they are my creations but I am allowing them to have a life of their own,” she adds. “If I imposed my personal politics on my characters, the book wouldn’t exist because they’d all be feminists (laughs),” the feminist author declares about her book where some of the characters are not.

There are two distinctly different schools of writers. The likes of Howard Jacobson and Leila Slimani, who begin writing from an idea and let the story take its course. Then there is the other school that has an Elizabeth Gilbert or a Yann Martel, who plan and note down their research before beginning to pen the story. Evaristo self-admittedly belongs to the first school as she tells us how her story began from “Carol, whose daily lexicon revolves around the orbit of equities, futures and financial modelling”, and she led to Bummi and her mother and from there arrived LaTisha and, subsequently, Amma, Yazz and Dominique.

“I didn’t sit down with a plan of writing about 12 characters, but I was aware that they all had to be of different ages, generations even, and they needed to have a different relationships to class and sexualities and occupations…. That was really important because I didn’t want to say that all of these women were straight, as that wouldn’t be true to life, and I also didn’t want it to be a token gesture of sexuality, which is why a quarter of them are in the queer spectrum. So, these were things I was figuring out as I kept writing, but I definitely didn’t sit down with a plan,” she says.

One of the the most striking elements of the novel is the form and structure of language, used sparingly in her last book.

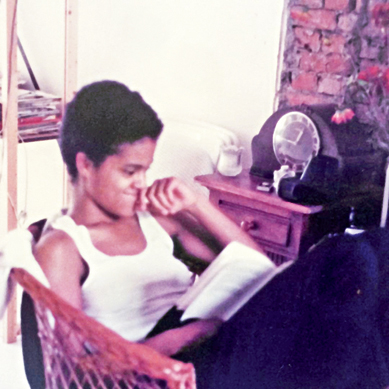

I was reading, always reading, the first step to becoming a writer. Poss ‘The Colour Purple’ by Alice Walker, from the stripey Women’s Press book spine. Amsterdam 1982/3. #thecolourpurple #alicewalker #womenspress #bernardineevaristo Sourced by the Telegraph

“Maybe some of their behaviour is unpalatable to you or that you don’t morally agree with it, but that doesn’t mean you should pre-judge it because if you do you will only end up with two-dimensional characters. In a way, you are going to force-feed the character to your readers with your judgements. And what the reader wants to do is make up their own mind. So, definitely, when I am writing all my books, I am allowing them to be who they are. Of course, they are my creations but I am allowing them to have a life of their own,” she adds. “If I imposed my personal politics on my characters, the book wouldn’t exist because they’d all be feminists (laughs),” the feminist author declares about her book where some of the characters are not.

There are two distinctly different schools of writers. The likes of Howard Jacobson and Leila Slimani, who begin writing from an idea and let the story take its course. Then there is the other school that has an Elizabeth Gilbert or a Yann Martel, who plan and note down their research before beginning to pen the story. Evaristo self-admittedly belongs to the first school as she tells us how her story began from “Carol, whose daily lexicon revolves around the orbit of equities, futures and financial modelling”, and she led to Bummi and her mother and from there arrived LaTisha and, subsequently, Amma, Yazz and Dominique.

“I didn’t sit down with a plan of writing about 12 characters, but I was aware that they all had to be of different ages, generations even, and they needed to have a different relationships to class and sexualities and occupations…. That was really important because I didn’t want to say that all of these women were straight, as that wouldn’t be true to life, and I also didn’t want it to be a token gesture of sexuality, which is why a quarter of them are in the queer spectrum. So, these were things I was figuring out as I kept writing, but I definitely didn’t sit down with a plan,” she says.

One of the the most striking elements of the novel is the form and structure of language, used sparingly in her last book before this one, Mr. Loverman, one that she terms as ‘fusion fiction’. There are no full stops and the sentences ride into each other in fluidic movements, creating a cadence of thoughts. Using the silences caused by the use of abundant space in each page, she succinctly used pauses and silences to speak more about the characters than words could have achieved.

“It was creatively liberating to get rid of the full stops. I think I invented the term ‘fusion fiction’ and nobody has told me I haven’t! It is fusion fiction not just for the absence of full stops, which makes the sentences, paragraphs and clauses merge into each other. It is also fusion fiction because the stories are fused together. There is nothing traditional, it’s very experimental. It gives a sense of a whole story but what actually happens is that you are just floating around into the minds and lives of these characters. I don’t think I would have been able to do this if I had written traditional sentences and paragraphs because it would have constrained me,” she says.

“Yes but I’m black, Courts, which makes me more oppressed than anyone who isn’t, except Waris who is the most oppressed of all of theM in five categories: black, Muslim, female, poor hijabbed she’s the only one Yazz can’t tell to check her privilege”

Checking of one’s privilege is an internal process, and very rarely is it pointed out successfully from the outside.

The concept of privilege can’t be simplified, the author feels, while creating a character like Yazz who pontificates on it extensively to whoever is willing to listen. “I find the idea of racial privilege very interesting because I understand the definition of it. There is a hierarchy of privileges, and when people talk about white privilege, they are often referring to white privilege as the most predominant and important privilege in society. When in reality, there is caste privilege, privilege of sexuality and so much more,” says Evaristo.

Is it this need for dogmatism and rigidity of thought in the name of ‘calling out’ culture that leads to people being ‘cancelled’ on social media terms? “When you have people cancelling other people, they are challenging them and their opinions. That should be a good thing, but if it becomes a shouting match or trolling, it doesn’t help anyone. We want debate, we want argument, we want to communicate and to understand each other’s viewpoints. But people tend to get too angry.”

It can well be argued, in retrospect, that a photograph of a protest march in 1982 in Brick Lane, London, can be mistaken for one in the US in 2020, if one looks past sartorial choices and sepia tones. This ‘anger’ has persisted and the conversations somehow remain the same. So has nothing really changed, we ask the author who has spent decades ‘in the fringes’ fighting the good fight.

“I think so much has changed, but we haven’t changed enough as a society. When I was growing up, there were no Black or Brown politicians in government and there were hardly any people of colour on television. People could openly be racist and get away with it because it was before the Race Relations Act (of 1965). We have made huge strides in many affairs, but there are still lots of problems such as young people of colour who are disproportionately arrested and sent to prison. We have a society where on the one hand we can see all these social developments, we have become more understanding of our differences, or even things like Gay Pride, which wouldn’t have been part of conversations in the ’70s but can now be enjoyed even by people who are not gay; but it’s still not enough. The relationships between Black people and the police continues to be problematic,” she adds.

The author misses her social life during this lockdown, stepping out to shop or meet up with people or attend events, while also simultaneously enjoying the solitary time. “I have enjoyed the quiet and lack of pollution, but I miss having my life back,” she ruminates. Exercising, eating and writing till 9pm takes up most of her day and she is reading The Lie of the Land by Amanda Craig right now and mentions The Vanishing Half by Britt Bennett as a standout read of the lockdown.

The only time we feel a chink in her armour of positivity is the mention of the future of theatre. “The daunting part is that a lot of these theatre houses might not survive this pandemic. That’s the worry. It’s probably true to say that a lot of them will go down,” said the theatre enthusiast in Evaristo, while hoping for a vaccine.

As we ask her about the television and film rights to the novel, her positivity is back as she talks of the deal that has been “signed and sealed but not delivered yet!” She may not be sure that it will eventually get made but “one can still get excited”, she laughingly adds!

We wind up the conversation by asking her if she experiences any added pressure after the Booker for her next book. “Up until now I was saying that there is no pressure, I am just going to write what I was going to write. But the more people ask me, the more pressure I feel! I think the pressure is always going to be there but I am just going to ignore it,” she ends with a hearty laugh.