It’s not easy for a youngster to step into the shoes of legends. More so when someone carries the double legacy of the rich traditions of Banaras gharana and a long line of musicians in the family. Wise beyond his years, Rohen Bose, son of the sarod maestro Debojyoti Bose, has managed to do just that.

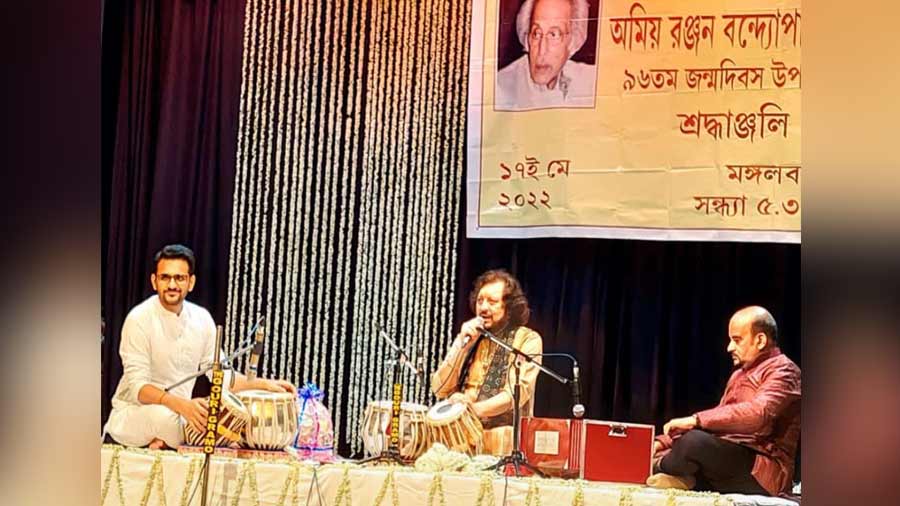

My Kolkata recently caught up with Rohen, the new whiz kid of the tabla, prior to his recent performance in tribute to Sangeetacharya Amiya Ranjan Bandhopadhyay on the occasion of the Bishnupur-gharana vocalist’s 96th birthday at Okakura Bhawan in Salt Lake.

My Kolkata: You come from a long line of musicians. It’s inevitable that you would be interested in music. But what exactly sparked your interest in music in general and made you take up the tabla?

Rohen: There has been a constant flow of music at home — I could hear someone singing, playing an instrument, practising vocals or simply listening to something when I was growing up. As everything around me has been engulfed by music, it was literally impossible not to get influenced.

My eldest uncle, Kumar Bose, has been a massive influence. He is my guru and taught me everything, including the nuances of the tabla, which has become my first love. I fell in love with this musical instrument because of its immense scope in the world of music.

Have you always been in love with Hindustani classical music? When did you feel the pull towards this domain?

Rohen: Born in 1992, I have been a typical kid of the 90s. I was not exactly smitten by classical music from the very beginning. I spent three years in Bishop’s School in Bangalore. Back then I was not at all inclined to consider music as a career and was enamoured by the film industry.

After I returned from Bangalore, I was admitted to St. James’ School in Kolkata. Though I was far from being a good student, the school happened to be a culturally active institution. I participated in all sorts of extracurricular activities and that was when I fell for music.

You said you were interested in the film industry. Can you say a little more about your interest in films and film music?

Rohen: Oh, I was totally in love with films and film music at that time! Having no inclination towards becoming an actor, I was more interested in being a technician. But here’s the anti-climax — I didn’t know that one needed to study Science subjects in their Plus-Two to pursue a technical career or a course in film-making. So I soon realised that I was not eligible for a technical course at any of the reputed schools.

Photograph: Avishek Dey

Were you still performing as a musician at that time despite your interest in other things? How did it help you along your journey?

Rohen: It’s true that I took part in one or two concerts by that time. I had been practising music for a long time, though not very seriously. Never for once had I thought that music would be a career option for me.

After my dream of being a film technician got crushed, I got enrolled in the music department of Rabindra Bharati University. Something extraordinary happened there — I topped my class in the first year! Having been accustomed to severe scoldings on account of studies all my life, I was now being praised and being seen as a future potential! It motivated me beyond anything.

My father, who had given up on my education, was pleasantly surprised. He insisted that I educate myself with proper tutelage before taking up music as a career. My days of fooling around were over as he made me realise that I would have to give up everything else to pursue music.

What was the next step in your career? How did the transformation begin?

Rohen: I began a documentary on my uncle, Kumar Bose, in the first year of college and decided to dive headlong into music. By that time my father was again ‘back’ in Hindustani classical music to pursue the sarod. Though I had taken part in other concerts, my debut concert — in the truest sense of the term — came when I got a chance to play with my younger uncle, Jayanta Bose, at Kalamandir in 2012 or 2013. After that, my eldest uncle took me for a solo performance at the Behala Saborno Sangeet Sammelan in 2014.

You enjoyed a good time at Rabindra Bharati University. When did you decide to break with your studies and completely immerse in music?

Rohen: My good results in the bachelor’s exam made it easy for me to enrol in the master’s programme in music at the same university. Upon completion of my postgraduation course, I went for a PhD in music. By that time I was performing regularly and sharing the stage with many stalwarts. In the first semester of my PhD, there was one very important seminar that I had to attend. As luck would have it, the seminar was on a day when I was to accompany the renowned flautist Ronu Majumdar. On that day, I decided to leave my PhD studies to become a full-time performer.

Photograph: Avishek Dey

Apart from Indian classical music, you have begun to make your mark in contemporary music. How do you balance the two different genres?

Rohen: I have always been on the lookout for a platform to experiment with my kind of instrumental creations. I launched a purely commercial band called “Rohen on the Rocks” in 2020 that plays instrumental covers of Bollywood numbers at corporate and private functions.

With my elder sister Mahiri Bose, I formed another band called “Rohen-Mahiri Project” in 2019. However, my focus remains on Indian classical music, which has been the core of my work.

What course the future will take is unsure, but I can share that I am getting into commercial ventures in a big way. For the moment, if I play 10 concerts, at least eight will be on Indian Classical music.

How do you think the musical scenario has changed over the years? And how has this influenced tabla players?

Rohen: Well, the definition of the tabla player has changed massively. In fact, the whole musical scenario has changed. Earlier, tabla players were placed behind other players on the stage. With Pandit Ravi Shankar bringing in a revolution in terms of breaking this age-old hierarchy, tabla players of my uncle’s generation started to be counted among the equals — they began to sit in the same line as the other players. Ustad Zakir Hussain has done a lot of different works in the composing realm. My uncle has also done a fair bit of work as he worked with film director Mrinal Sen as an assistant music director.

As tabla players of this generation, we really want to accompany stalwarts in musical performances. At the same time, we want to do some compositional work on our own. Our horizon has expanded thanks to the relentless work done by tabla players of previous generations.

Tabla for future generations — how do you plan to inculcate the ethos of this musical instrument in future generations?

Rohen: Our family has been teaching music for generations. I too have been doing so for many years now. My uncle gave me two students when I was in the first year of college. Now I teach around 30 students. Our music school is known as Bose Foundation for Art and Culture. A brainchild of my father, the foundation is going to do some unique collaborations in future.

Do you have any personal regret as a practising musician and a teacher?

Rohen: I belong to the Banaras gharana, which has a strange masculine approach when it comes to the spread and practice of the art. Only recently Hetal Mehta, a lone performer of our gharana from Gujarat, has come up. I admire her capabilities as a tabla player.

However, I remain hopeful that we will one day see a feminine aspect of the gharana. It could provide a new and completely different dimension that would emerge from women players and performers.

As someone who is obviously an achiever, what would you like to tell students and practitioners of the art of the tabla?

Rohen: The future of the tabla is remarkably bright. But we need the courage to override our inhibitions and prejudices. Being open to experimentation can actually open a lot of doors in today’s world. Respecting and upholding traditions and institutions is, of course, important as they represent the fundamental aspects of music and creativity.

It’s important to remember that doing something new doesn’t mean any deviation from the basics. We need to build a fantastic future by combining new ideas with our glorious past — it should be the aim of everyone who wants to make it big in the industry.