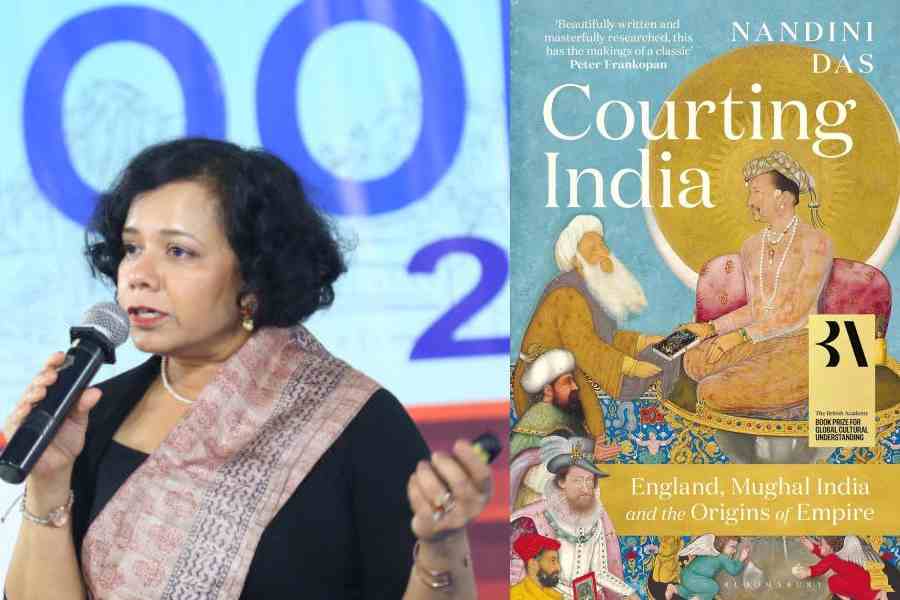

Academic and author Nandini Das calls her visit to Calcutta, after six years, “bittersweet”. “I grew up in Calcutta, but the kind of drive to come back to Calcutta has lessened since my parents died. So I tend to go to Delhi where I still have family, but it feels rather bittersweet to be back in my familiar city,” said Das who was in the city to discuss her British Academy Book Prize-winning book, Courting India: England, Mughal India and the Origins of Empire, which chronicles Thomas Roe’s arrival and four-year stay in India as James I’s first ambassador to the Mughal Empire under Jahangir.

Explaining the “bittersweet” emotion, she said: “I think for most expats, whether you’re moving internally within the country or abroad, have this feeling that their image of their space is like a little time capsule. And the reality never quite matches up with that time capsule. So you have that strange sense of dissonance between the two.”

Despite the dissonance, there’s a sense of joy in her voice and she mentions the charm and nostalgia of the Book Fair that has been the biggest drive to get her back to her city. “I’m a working academic, so it’s a busy time in terms of my academic commitments but Calcutta Book Fair was such a fixity in my childhood calendar, annual calendar, that I wouldn’t miss this chance for the world,” said Das as she sat with us at the UK Pavillion after a session organised by the British Council.

Since you’re a full-time professor and have commitments, how long did this book take to finally come out in print?

Well, quite a long time. This is a debut book in terms of trade books or wider readership books. I’ve been working on Roe as part of my research for about a decade and the reason it took about 10 years is because so much of the material is manuscript. This isn’t a case of going and finding something that’s nicely printed and then using that to write your book, and honestly, some of the people whose reports I was looking at have dreadful handwriting. So looking through 17th-century letters takes a long time but I’m really glad to be able to distill a lot of that into the book. So there are moments when I’ve been tempted by funny stories from ordinary merchants which you don’t usually otherwise get in our sense of history.

Ten years is a long time. What is it that kept you going and not leaving the book midway?

When I started working on it, I didn’t think about whether I was going to publish it. I was researching because it seemed I had questions and as a historian, I wanted to find out those answers. As a political researcher, you’re kind of like a detective in the sense that you follow the clues and you see where they take you. And then about four years ago, before the Covid pandemic, I was asked if I would write a book that is for a wider readership, a non-specialist readership. And then the book became one of my escapes, my sane escapes.

You have written a few academic books. How different was the experience of writing a book that’s for a wider readership?

When I started thinking about writing this book, I realised that it was a story that perhaps a wider readership would be interested in and it’s a story we need to be more aware of. So I started writing it in a way that would perhaps make it more approachable for others who might not be deeply interested in the minutiae of history. It was challenging in the sense that I was trying to bring in very many different strands. So there’s one way of writing about British Empire or British presence which puts that English presence centre stage, and, of course, Roe is centre stage in this book, but I wanted to shift that lens and I wanted to look at him from other lenses. Like ‘What did the Portuguese say?’ ‘What did the Dutch think of him?’ ‘What did the Mughals themselves think of him?’ Putting that jigsaw together was the main challenge.

During the session, you said some things were a revelation to you while you were doing your research. Can you elaborate on a few?

There’s lots of interesting research going on now about Mughal women but I hadn’t realised the extent to which they were not only educated but also deeply interested and involved in politics and trade. Within Islamic financial laws, the women could keep control of their own money, of course that’s not to say that they weren’t governed or influenced by men, of course they were, but at least legally they had a stance. And many of the Mughal women invested in public works, they invested in trade, they had their own artists so I found that really interesting.

You bring a very interesting perspective in the book — while on the one hand we see how Roe perceives India, on the other, we see Jahangir’s viewpoint as well. Tell us more.

Roe is the first English ambassador to be sent to India and being the first puts him in a particularly difficult but also particularly influential position. And I think in order to understand the later history of British Empire in India you have to understand the point of origin and in many ways Roe is that point of origin. Jahangir also is hugely interesting because of his own memoirs in Jahangir Nama, and at the same time, Roe is writing his diary. So that gives us a very rare occasion where you can see the same historical moment in this period from two completely different lenses.

Since we are talking about the start of the British Empire, does Calcutta feature in Roe’s expedition to India?

There’s a moment in Roe’s diaries where he is desperate to get a trading license for Surat in Western India and has been waiting for a while and getting nowhere with the Mughal court. He writes this account in one day’s entry where he says, ‘I’ve been talking to the advisors of the Empress’ — by that he means Noor Jahan — ‘and apparently on the other side of India there’s this place called Bengala and the Empress suggests that we should look there for a trading license’. Now, of course, Noor Jahan’s first husband was the governor of Bengal, so she was deeply familiar with Bengal. So there is something in this story.

Talking about the kind of books that you read, are there any influences of other authors in the book?

Well, that’s a very difficult question to answer. I’m a scholar of English literature, I read quite widely in that sense so I don’t think I could pin down a specific influence in terms of style. I told the story in the way I thought would work well for the story. I’m sure no doubt there are multiple influences in there but I suppose in some ways because I work on this period and work intensively on the literature of this period, what I’m particularly conscious of is the tone and the texture of English language of that period which is what I’ve tried to get through in the book as well.