Now, when the drums of war beat louder and the loss of life seems unstoppable with the Asia being wrested by two monoliths, China and Russia, Christopher Koch’s exploration of the vulnerability and exploitation of human innocence, as lucidly told in his sixth bestselling novel, Highways to a War, becomes a warning about the fragility of life.

Christopher Koch, who would have been 90 this year, could be celebrating his unmatched success as a writer in the happier celluloid paradise out there somewhere. He was catapulted to fame with The Year of Living Dangerously (1978). It was the first Australian novel which received a six-figure advance. Once literary agent Andrew Wylie sold it to Viking, Koch went from relative obscurity to celebrity. And that wasn’t even half the journey to fame. The Year of Living Dangerously was transformed into a mammoth box-office success by Peter Weir, 40 years ago, in 1982, with Guy Hamilton (Mel Gibson) a journalist on his first job in Indonesia during the last years of President Sukarno’s regime.

He is helped by his photographer, a half-Chinese dwarf Billy Kwan (Linda Hunt) and diplomat Jill Bryant (Sigourney Weaver) who plays the romantic interest. And it is still very relevant not just because it earned Oscars for exceptional performance and screenplay, but also because the meticulously researched novel captured the tumultuous history of Indonesia under the frightening autocracy of President Sukarno and exploded it on millions of readers and cinema-goers worldwide.

Historically, it corralled the escalating violence in an idyllic land and Koch’s ability to seamlessly marry the sorrow of separation between friends and lovers in the arena of war continues to amaze after four decades. It was compared favourably to the fiction of Graham Greene. Anthony Burgess paid Koch a significant compliment in Times Literary Supplement of Britain that the piece of fiction was “intelligent, compassionate, flavoursome, convincing, and well constructed”.

Quietly stirring, and packing a punch with haunting language, Koch’s ability to align the urban and rural landscape with the humans who inhabit the spaces grabs the readers’ attention. Thus: “Most of us become children again, when we enter the slums of Asia. Last night I watched you walk back into childhood, with all its opposite intensities. Laughter and misery and the crazy and the grim. Toy town and city of fear.” The reader can smell and breathe the fear in the dialogue and the author’s presence is palpable in the narrative: “There’s a definite point where a city, like a man, can be seen to have become insane”, Koch wrote in The Year of Living Dangerously. “This had finally happened to Jakarta.”

Koch won the Miles Franklin Award twice. An old Asia hand, born in Hobart, Tasmania, in 1932, of Anglo-Celtic descent, he wrote nine books, of which six are novels. He is considered one of the frontrunners of the loosely woven war correspondents and writers fraternity of the Vietnam War, though Koch never visited Vietnam or Cambodia during the war, only going there in 1987.

The horror and bloody history that he saw unfolding through his thirties and forties, from Singapore, through Indonesia and then Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, gripped his imagination. As his colleagues — correspondents and combat cameramen — often stated: “We are fighting someone else’s war.” And Koch felt the same.

In an interview with me, in December 1995, he had categorically stated: “It was a juggernaut that drove the destiny of much of Asia right from the 1960s onwards and the scale and acceleration of the churning was incomprehensible sometimes. Youngsters who were soldiers from half way across the world, correspondents, cameramen, were all targets for the machinery of war, of change and power.”

I had heard echoes of the same powerful sentiments from the old veterans who had returned from the Vietnam War, whom I spoke with when I worked as a journalist at the Ministry of Veteran’s Affairs in Canberra, Australia. Many Vietnam war veterans I met were suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, virulent skin eruptions, sleeplessness, rage — all severe after-effects of Agent Orange, the chemical that the US sprayed for defoliation of Vietnam so they could “see” the enemy. The Australian veterans felt used and stated: “We were sent to fight someone else’s war,” and “Look what happened to us with the chemicals that we were spraying us with.”

A still from the 1982 film based on of Koch’s The Year of Living Dangerously

Koch’s father was an accountant. Koch recalled in his interviews that the Hollywood star Errol Flynn’s initials were carved in a desk at the school from which both he and Flynn were expelled. Interestingly, it was Errol Flynn’s son Sean Flynn, who was captured by the Vietcong and murdered by the Khmer Rouge.

Koch’s contemporary and acquaintance, combat photographer and author Tim Page spent a decade looking for Sean Flynn’s remains in Vietnam. The story is told with attentiveness and care by Page in Derailed in Uncle Ho’s Victory Garden. The Vietnam war correspondents and cameramen were a close-knit brotherhood of gifted and intelligent youth, and though they were occasionally not on the same page with the politics, the intimations of mortality and how tenuous it was to be so close to document the events at the firing line, sutured them together.

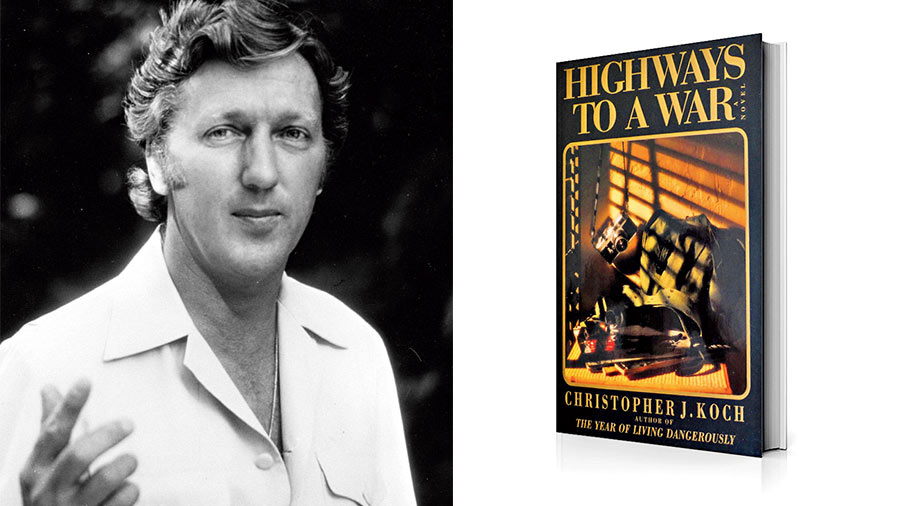

Koch was fascinated by the lives they led and the imminent danger they faced constantly. His celebrated novel Highways to a War was written with years of “inner prodding” and he characteristically made notes for a year and more, creating his protagonist Michael Langford, from the lives of Neil Davis, Tim Page and others.

What about the observation that Koch had constructed Neil Davis on his brother, who was a correspondent? Koch denied this vehemently. He said to me: “I never base my characters on one person from life. I use a host of people to create my fictional characters. So though some people said ‘Oh! Neil Davis in Highways to a War is (my) brother’, who was an ABC correspondent, that’s not true. I have never been a journalist or a foreign correspondent. Correspondents fascinate me. I have picked the brains of some, and I have included some of their experiences because I didn’t have exactly that experience .”

Koch typically worked seven-hour days, five days a week and delighted in the writing process. He found employment at a bookstore in Tasmania, but lost his job for spending a great deal of his working hours reading. Subsequently, Koch was employed in the art department of a newspaper, before graduating in 1954 from the University of Tasmania. He went on to live in India and England in the 1950s, published his first novel in 1958, and then went on to studying writing at Stanford University.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation hired him from 1963-1972. He spent two months in Indonesia in 1968, helping set up an educational broadcast network. As he decided to give up his day jobs, and give everything to writing, he hit his stride, never to look back again.

Neil Davis (left) and Christopher Koch’s Highways to a War (right), which was based to a large extent based on his life

RELIVING BLOODY DAYS

Tasting of nuoc nam (the typical sharp-smelling fish sauce of Vietnam), Agent Orange, and shrapnel, Highways to a War, Christopher Koch’s riveting sixth novel, stands out as a spectacular piece of Vietnam War literature. This is even more compelling than his The Year of Living Dangerously and better scaffolded than the widely lauded The Doubleman. Koch won the Miles Franklin Award for both The Doubleman and Highways to a War.

I met Christopher Koch and his charming wife Robin in 1995. It was the year of living his dream. Koch said to me that his sixth novel “Highways to a War is the best and the most complex of all the novels” that he had written. “The core of Highways to a War is myth. It’s the story of a man who becomes a myth in other people’s minds.” He was in Singapore, as a distinguished speaker, when the book had just been launched. And it was the same year that he won the second Miles Franklin award.

Highways presents the human face of war, one that is fuelled by the egos and moral lapses of political hustlers, traders, and war-mongering heads of states. That’s the hard shell which ensconces part. Koch is the quintessential story spinner who ever so subtly unveils the story of friendship, steamy passion, lost love, searing pain of a genius who pushes lady luck too far, believing he will live through all the frontlines.

The novel traces the many-pathed journey of a young Tasmanian farmer’s son, Mike Langford. Fellow Tasmanian author Koch paints a most alluring picture of the colourful hop fields of New Norfolk. Langford’s trajectory takes him through sixties Singapore, sleazy Saigon, and majestic Phnom Penh of the early Seventies where he becomes an acclaimed combat photographer with an almost insatiable appetite for the thrill to get closer and closer to the front.

It ends with Langford’s mysterious disappearance in Cambodia and the subsequent murder at the hands of the Khmer Rouge.Throughout Langford’s life, he keeps on the straight and narrow, and insists on doing what he believes is right. Narrated by his childhood friend, Ray Barton, who subsequently becomes his lawyer, the novel uses the polyphonic mode.

The voices of Langford’s friends — Jim Feng, a Hong Kong-based cameraman; Dmitri Volkov, a Russian emigre-French-educated cameraman; Harvey Drummond, a war correspondent — all add to a polyphonic telling. A collection of tapes (Langford’s talking diary of 11 years) textures the narrative and adds to the mystery of what actually happened to Mike Langford.

Using the same technique but with a refreshing ear for detail, Koch, like Michael Ondaatje retelling the history of his father and fatherland in Running in the Family, adds a multiplicity of perspectives and leaves the reader hungry to discover — so what really happened?

It is thrilling at times (when Langford, Volkov and Feng, who are prisoners of the Viet Cong), poignant at other times (Langford’s unfulfilled relationships with Vietnamese shanty dweller Kim Anh, and Khmer lover Ly Keang), idyllic at others (when Langford is a strapping youngster in Tasmania, lending Koch a bird’s eye view and a kaleidoscopic series of images that enhances the suggestion of an infinitely fragmented world.

Mike Langford is an ordinary man whose extraordinary pursuits and indomitable spirit of goodness influenced the lives of all he touches. This novel was inpired by the life of Neil Davis who was Koch’s schoolmate in Hobart High. Davis was an outstanding cameraman in Indochina, killed while covering a Thai coup in 1985. Koch cautioned me: “I’d like to get it very clear to you that Highways is in no way a fictionalised biography of Davis. Mike Langford is not Neil Davis.”

“Neil’s biography was written by dear friend and fellow Tasmanian Bill Bowden. His book One Crowded Hour did much to set me thinking when I planned this novel.

“I never create a character out of only one person. Langford was also based on Tim Page, the brilliant English war photographer who took some of the greatest still photographs of the war and who is portrayed by Michael Herr in Dispatches.

“Tim’s own book, Page After Page (which was reviewed on September 13 in The Telegraph), was also an inspiration but I didn’t meet him until in London when Highways was launched. He seemed on the whole to think that I got it right, which pleased me. I think it legitimate that a writer should take as his inspiration the personalities of various people to create his character or characters. Tolstoy did it all the time: people recognised their friends in War and Peace.”

The intertextuality between Tim Page’s unforgettable memoir Derailed in Uncle Ho’s Victory Garden, where Page travels to Vietnam decades after his friend and soul brother Sean Flynn, the Hollywood actor Errol Flynn’s son, had been captured by the VietCong, and handed over to the Khmer Rouge, who murdered Sean, and the mysterious disappearance of Australian combat photographer Neil Davis is undeniable.

Koch keeps the reader in suspense as he surreptitiously nudges her on through the frenzied, battle-scarred life of an exceptionally talented combat photographer. The first 60-odd pages about Langford’s childhood in a Tasmanian farm are narrated with lyricism and grace that chime with the peace and beauty of the Nottingham countryside in England, in D.H. Lawrence’s The White Peacock and the Rainbow.

His ability to write about the beauty of nature and paint the horror of the Vietnam War with equal adroitness gives his writing a versatility and verisimilitude that can only come from a writer who can engage with both immense horror and exceptional beauty: “Streaks and shafts of light leaked through the windows and lay like syrup on the sacking.” And for the hop fields: “The very light was green, the glades like the emerald glowing church of an unknown sect.”

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography 'Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen'. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Kolkata and teaches Masters English at Loreto College.