Before an ‘accidental’ opportunity came his way in 1999, involving a short-term project on Bengal’s watercraft under historian Dr Lotika Varadarajan, maritime ethnography and maritime archaeology were words north Kolkata’s Swarup Bhattacharyya had never even heard.

So, he was lucky to find a role in the project executed by the Department of Ocean Development and funded by the National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies. And as luck would have it again, the project turned out to be a turning point for Swarup, and unveiled a whole new world to him.

Son of sculptor Madhab Bhattacharyya, Swarup was always a brilliant student, but this experience motivated him to spend the next 20 years researching and documenting the marine heritage of India’s eastern coast, specifically Bengal and Orissa.

Recalling his first experience of watching boat-making, he says, “The first time I saw artisans making a boat was under the shade of a tree in a small village called Pashchim Gadadharpur, near Digha. For me, it was no less than magic — seeing the humblest and most-marginalised people of our society display such engineering and artistic skill in converting some logs into a mode of transportation.” It thrilled him to no end and soon, the subject grabbed his entire attention.

Bhattacharyya’s first experience watching boat-making was ‘was no less than magic’ Shutterstock

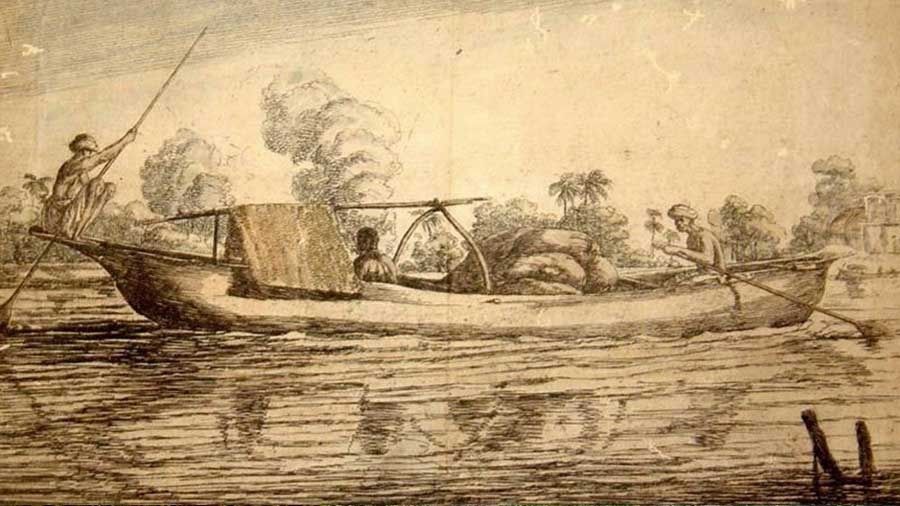

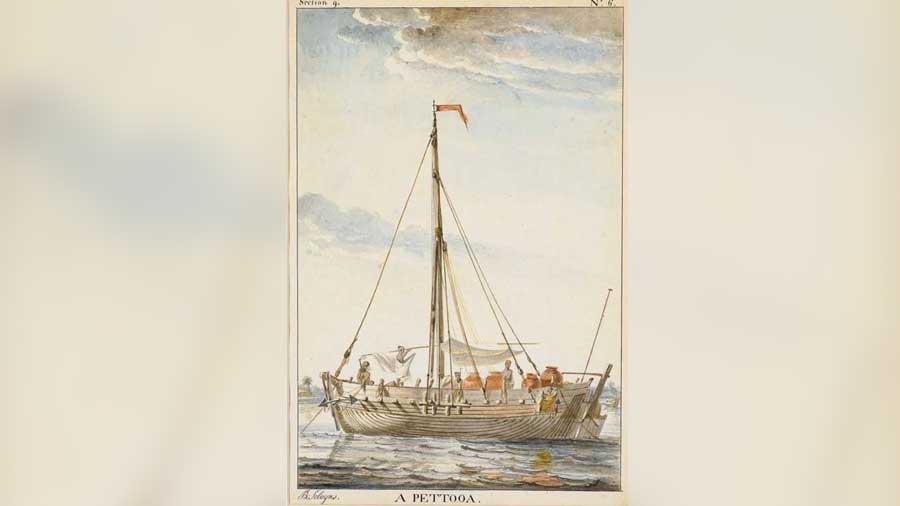

A voracious reader, Swarup began looking for books and periodicals at various libraries, and to his surprise, he found two gems. First was a 1946 book by English zoologist and seafaring ethnographer James Hornell, who was director of the Madras Fisheries Department. The other was an even older book, by marine painter and ethnographer FB Solvyns, published in 1799. In both books, Swarup found basic details on water vessels made and used in India, as well as information on the boats of Bengal. These pioneering works fed his desire to know more about Bengal’s watercrafts and their heritage.

Bhattacharyya’s copy of English zoologist and seafaring ethnographer James Hornell’s book Courtesy: Swarup Bhattacharyya

“I was moved to see the dedication of those so-called ‘foreigners’, who had so systematically documented various types of boat-making in Bengal and Orissa, as well as the social customs associated with it. It inspired me tremendously and I decided to explore this more,” Swarup says.

Continuing, Swarup said a boat is more than just a water vessel: “One can understand the geographical characteristics of a region from the shape and technology of a boat. In the east coast of India itself, there are 30-odd types of non-mechanised boats and each of them is made to negotiate with the waves, winds, water depth and other navigation issues of its course. Patia, hala, goulia, paukiya, chhot, sultani and betnei, to name just a few, are part of our maritime heritage.”

A painting by Flemish marine painter and ethnographer FB Solvyns, who lived and worked in Calcutta in the 18th century Wikimedia Commons

He mentions that all these creations came from people who had not gone to any engineering colleges, let alone to schools, in their lifetime.

“A boat-maker considers his boat to be his daughter. He not only fathers her, but also makes her strong and beautiful. He cries the first time a boat first goes in the water, and at the same time rejoices to see her survive on her own. Before a boat is launched, a series of rituals are observed for its long and safe voyage. The day is no less than a festival for both the owner and the maker of the boat,” he explains.

‘A boat-maker considers his boat to be his daughter. He not only fathers her, but also makes her strong and beautiful. He cries the first time she first goes in the water,’ Bhattacharyya says Shutterstock

It also pains him to see no efforts being taken to highlight this rich cultural heritage. So, in the true ‘Ekla Cholo’ spirit of Bengal, Swarup has been documenting and collecting information about boat-making since 1999 by visiting various fishing hamlets of Bengal and Orissa. Needless to say, he has no support or financial interest in this endeavour.

Swarup also tried to convince many top institutes of India to take an initiative on this subject. “I wrote several mails to the National Institute of Oceanography, the National Institute of Ocean Technology, the Indian Museum, the Calcutta Port Trust, the Birla Museum and even to the Discovery and National Geographic channels — but got no response from anyone,” he sighs.

Models at Bhattacharyya’s home Courtesy: Swarup Bhattacharyya

But recognition came from foreign shores. A 20-page article, with 15 photographs, that he had sent to Technique & Culture magazine of Paris on Bengal’s Patia boats was published and was widely appreciated. This was followed by a surprise letter from the Viking Ship Museum of Denmark in 2001, inviting Swarup to visit Denmark and work in the museum for three stints of two months each.

FB Solvyns’ illustration of a Pettooa (Patia)

The visits changed Swarup’s world of forever.

He learnt how the maritime cultures of foreign countries are studied and preserved. “They not only have models, but also make replicas of ancients ships and boats for common citizens to see and use. For them, a museum is not a dumping ground of relics — it is a centre to make citizens aware of their history with live experiences. We Indians must learn how to develop an interest in our heritage,” he says.

A close look at the wood craft applied in boat making, in a miniature by Bhattacharyya Courtesy: Swarup Bhattacharyya

From Denmark, Swarup made trips to England, Sweden and Germany to study more about the evolution of European marine vessels and the cultural heritage related to it.

And from 2003 onwards, Swarup began getting responses from some other organisations too, beginning with an invitation from the Nehru Trust to speak on the ‘Boat Race of Bengal’. In 2004, his exhibition on miniature boats and photos at the Bagbazar Utsav got media attention. The Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage also consulted him in building a maritime museum in Orissa and IIT-Kharagpur has displayed his work in their museum.

Bhattacharyya at an exhibition on traditional boats at Sidho Kanho Birsha University, in Purulia in 2017 Courtesy: Swarup Bhattacharyya

In 2006, the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts organised an exhibition of his works in Delhi and Sea Explorer Institute invited him to display his works at a river festival held at Prinsep Ghat.

“I contacted former IPS officer Upendranath Biswas for a permanent exhibition on Bengal’s boat heritage and he was kind enough to arrange a space at the Institute of Cultural Research in Kankurgachi, where in 2014, the Heritage Boats of Bengal gallery opened with 46 miniature models of various water vessels and their related history — all made and compiled by me. But the gallery hardly attracts any visitors,” Swarup rues.

The Heritage Boats of Bengal gallery at the Institute of Cultural Research in Kankurgachi

“I’ve never had a permanent job. I still survive on the contractual remuneration I receive from various government institutes where I work as research fellow. But during lockdown, I had no income as there was no renewal of any contract. I overcame that gloom by reading more about boats and making several small models. I survived, and I must say that I am perhaps the only person in India who survives by keeping his passion for boats afloat,” Swarup signs off, with a hint of contentment on his face.

‘A museum is not a dumping ground of relics… We Indians must learn how to develop an interest in our heritage,” Bhattacharyya says Courtesy: Swarup Bhattacharyya