Louise Nicholson founded Save a Child in London in 1985, to support disadvantaged Indian children so they can have better opportunities. She spent her childhood in the idyllic English countryside of Surrey and Sussex, encouraged by her mother to go to Edinburgh University to study art history instead of becoming a housewife. That was the beginning of a career in art where she studied, in particular, India’s many cultures. By establishing Save a Child, she enabled people, who she knew wanted to help Indian children, to do so in a simple, no-frills way. So far, some 3,500 children have benefited from their support.

My Kolkata talks to the British art historian to discover how she came about establishing a global charity in India.

My Kolkata: What drew you to India in the first place?

Louise Nicholson: My training as an art historian led to working at the art auctioneers Christie's, in London. I was one of two people that made up the department with the ridiculously wide-ranging title: ‘Indian and Islamic Miniatures and Manuscripts’. To make it even more crazy, its geographic scope was Spain to Malacca, its timespan 11th century to the present. It was a very exciting period for this fairly new area of art history, with trailblazers publishing new theories in catalogues and journals. Our catalogues contained a lot of primary research. The job opened my eyes to the remarkably long, diverse and rich cultural history of India. We had pieces produced in Hindu, Jain, Sikh and Islamic traditions. In fact, some of the best Islamic paintings were made at the Indian courts.

Did you get to visit India soon after?

When I married in 1980, India was the obvious place for our honeymoon — my first encounters were the Ajanta and Ellora caves, a houseboat in Kashmir, a memorable bumpy, back-seat bus ride through Rajasthan and the Ganpati festival in Mumbai. Two years later, when I was working on The Times arts pages in London, I proposed to the brilliant editor Harry Evans that I write a weekly column explaining the events in the year-long Festival of India in Britain. I argued that India had been a major part of British history in many ways and now many Brits, including Asian Brits, did not know much about India's amazing culture. He bought the idea, and week after week I met extraordinary people bringing India's dance, theatre, textiles, art and music to the UK. Many have become lifelong friends.

How did you become a tour guide in India?

People started asking me for advice on their trips to India. The only guide books were written by committees of people who were often more interested in where to find the cheapest samosa than where to see great weavers, or the best times to see the great buildings well-lit. So, I decided to write the guide to India that I wished had existed when I’d been a tourist there. I must have been totally crazy! I had no idea the work it entailed. Somehow, I did it. But really, it was India that had done it, that had given me the curiosity, energy, staying power. Now, I wanted to give something back to India. When the book — India in Luxury, a Practical Guide for the Discerning Traveller — was published, I was asked to lead trips to India. In the book title, the word ‘luxury’ refers to the luxury of experience, whether it’s seeing a fine building at sunrise, drinking chai from a terracotta cup or observing the magic of weaving. Soon however, I created my own tours, especially after I had been associate producer for the six-part TV series The Great Mughals, with Bamber Gascoigne. I still create group tours and private ones, all over India.

(Read more about the tours here.)

When did you conceive of the idea of Save a Child?

When the book was published in India and I did the press rounds in Mumbai, Delhi and then Kolkata, I told friends about my quest. On May 12, 1985, at 8am, a friend introduced me to Shyamali. She was seven years old, wasn’t going to school and had been working in a hair salon for two years, breathing in hair lacquer spray and dust. I decided on the spot to support her so she could live at All Bengal Women's Union Welfare Home for Girls — the long-established and much-respected residential home in Elliot Road, Kolkata.

Save a Child was born.

What makes Save a Child unique?

Back home, I established Save a Child charity to give deprived children in India a fresh chance through long-term support. This is our USP. It is backed up by a second one — our annual field trip to meet with every child we sponsor and then send a photo and report to their supporter. Thirty-seven years on, Save a Child has helped over 3,500 children transform a bad start in life into a happy, secure, healthy, fulfilling one with great education, well-developed hobbies such as dance, art, cricket and football, and incredible achievements such as going to university to study science or engineering, or even becoming a doctor.

What does the field trip involve?

We do a field trip each year to meet each child and photograph them. But Covid caused a two-year stop. In November 2022, I did our first one since 2019. I met, talked to and photographed almost 300 kids! It was so heartening to see how each child has developed. The staff performed miracles to put learning online when the children had to return to their homes. Now the kids are so happy to be back with their friends, their classmates, their hobbies such as yoga, dancing and football. And just messing about together, at our various 'homes'.

Once home in the UK, I write to each supporter personally with news of the child they support, conveying their progress in school and community life. I also send the supporters a photograph of the child. It’s a big job to cheer me through chilly December!

Tell us a little about how the sponsorship programme works.

We have about 250 supporters for about 300 children. Most support one child but some people support two, three, or more. It's really wonderful and touches my heart every day. We are very clear that it is a long-term commitment. Most of our supporters feel huge fulfilment in knowing they are transforming a child's life for the better and for always through long-term commitment. Supporting a child is a win-win!

Supporters give $300 a year which pays for a good amount of a child's needs. In return, supporters receive an annual report and photograph, so they see the child's progress. If a supporter travels to India, they sometimes get in touch with me and I work with the homes to arrange a visit. It is absolutely always a landmark experience for the supporters. It's hard to imagine just how amazing these homes are until you go in person.

The field trips gave Louise Nicholson a chance to meet the families of the children. 'For the first time I met the mothers/grandmothers of some girls supported by Save a Child'

What are the ways in which Save a Child saves its children?

We fund professional counsellors for the traumatised children arriving in our homes, who have suffered atrociously in their early years. We fund Spoken English lessons which help kids in English-medium schools and later during skills training and the job market.

Up near Purulia in rural West Bengal, we fund local village girls to come to the superb RKVM schools as day students, and they carry their knowledge back into their homes to share with mothers and family — it's a new project that's taking off with great success. We also fund football training at RKVM, which exercises and exhausts the teens in a good way, and gives them team skills they can use in their jobs. There's an inter-home league with a massive trophy! It's highly competitive to get on the training scheme, so we are about to expand it.

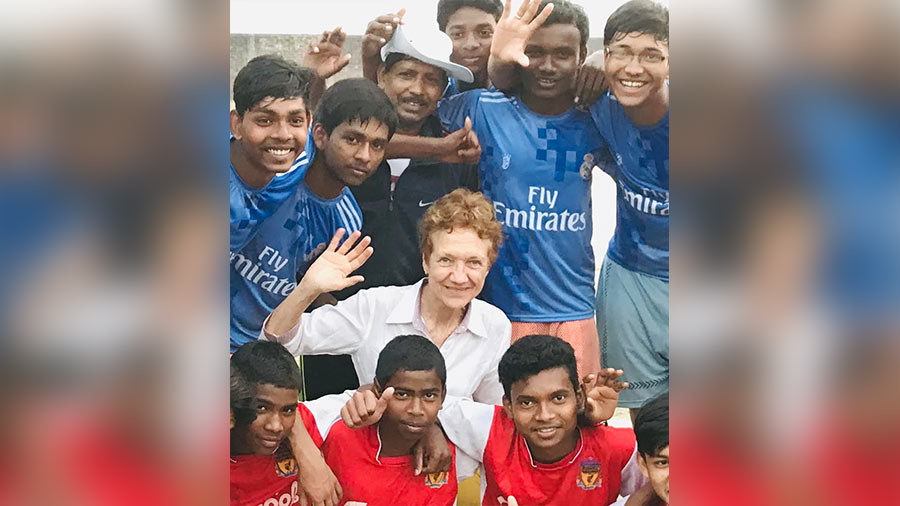

Louise Nicholson with supported SaC kids during a football training programme: 'Each year we have more and more children going to college, with ambitions to be teachers, nurses, soldiers, policemen, engineers, doctors!'

What are some of the homes you work with and where?

We work with All Bengal Women’s Union, Ramakrishna Vivekananda Mission and Shri Digamber Jain Mahila Ashram. Our relationships are collaborative. The field trip is an important time for discussions with all the staff – from carers and counsellors to teachers and football trainers. It has to work both ways for the staff and above all for the children. For ABWU, a friend introduced me to Shyamali who had a chance to go and live there. That was the start. RKVM in Barrackpore was also a suggestion from a Kolkata friend. It is an entirely different kind of institution, founded on Vivekananda's core aim for 'upliftment of the very poor through education'. When we started our collaboration, it was mainly for boys but now they also run an excellent girls’ home and school as well as another home at nearby Suryapur for girls who are doubly deprived, poor and either speech and hearing impaired or blind.

In Delhi, the small Jain Ashram for girls, just south of the Red Fort walls, is run meticulously by Ritu Das whose grandmother founded it. Supporters visiting India often come through Delhi, so this is the home they are most likely to visit. The girls are incredible, they have some capital city confidence, you should see their yoga-gymnastics performances!

Where do you see yourself and Save a Child go from here?

Now that I'm getting old (into my 70th year next birthday!), I'd like to pick and choose my work so I can give more – much more – time and effort to Save a Child. In our current global economy, fund-raising is much more difficult and attitudes about how best to help other people have changed. I think there might be fewer people up for the long-term commitment to one child (though I hope I'm wrong). But I'd like to expand Save a Child's several projects which are already solidly in place.

What gives you the inspiration to keep doing what you do every day?

Ambitions of the caregivers for the children (and even of the children themselves) have radically changed. Back in the '80s, the ladies caring for the girls wanted to get them married – it was seen as making them entirely safe for life. Today, the girls are encouraged to continue to Class 12, to go to college, to pick up skills which can make them self-sufficient and not reliant on a husband who could lose his job or have an accident, etc. Boys are also encouraged to aim high, to take education as far as 'their ability and their aptitude' permits, as Swami Nityarupananda, Secretary of RKVM, puts it. Each year we have more and more children going to college, with ambitions to be teachers, nurses, soldiers, policemen, engineers, doctors!

Seeing the transformation of these kids as they build confidence, seeing them flourish, seeing them springboarding onto their own adult paths, all of that inspires me.

What was the real eye-opener for you while you were ‘saving' the children?

The huge eye-opener was how fast a safe environment with love, nourishment, attention to mental and physical health, friendships and good schooling can mend and transform a child. I see how deprivation and sadness can transform into a happy childhood with an optimistic future.

When you’re not keeping up with the lives of the children you’re invested in, what are you doing to unwind?

Seeing my sons and three grandchildren, gardening my walled garden in Gloucestershire, walking around the Cotswold hills, reading, looking at art, listening to music and the BBC’s ‘In Our Time’ blogs, cooking, sharing meals with friends. My days are often a muddle, I’m always aiming to do too much — re-writing to-do lists, working alone, seeing friends to enjoy art and music, a roller-coaster that I enjoy so much. The loneliness of Covid isolation was awful. But it made me value my friends better, and I think it made me a better friend.

Read more about Save a Child here.