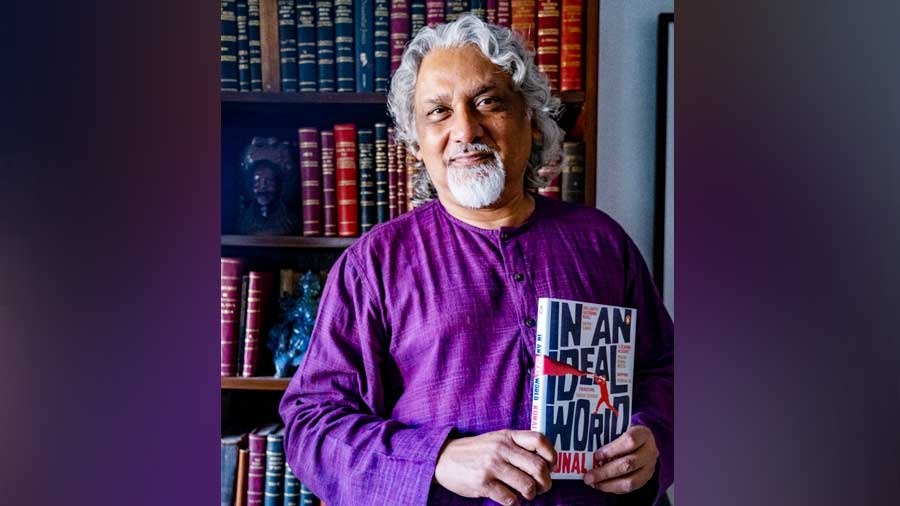

Kunal Basu is a worried man. Worried about the discourse that has invaded our homes. Worried about the ugly words that have come out of their hiding places and taken centre stage. He has poured his anguish into his latest work, In An Ideal World (Penguin Random House India, p 198, ₹599). Member of Parliament Mohua Moitra summed up the essence of this novel very well in a recent tweet: “The dangers of everyday prejudice turning into full fledged hate; when no one can separate the political from the personal.”

The author of novels like The Miniaturist, Kalkatta, The Opium Clerk and many more, as well as the well-known short story, The Japanese Wife, welcomed My Kolkata to his book-lined home in south Kolkata to talk about In An Ideal World, Kolkata’s place in it and his own days of student politics.

My Kolkata: In an Ideal World is a brave, brave book…. How did the idea come to you?

Kunal Basu: This novel was written in anguish, to be perfectly honest. Anguish at the culture of hate that has permeated our society. You know, I never start a novel with a theme in mind. I didn’t tell myself that I have to write a story about Hindutva versus secularism. Because I never do that. But living in India, one breathes the air of this place, listens to arguments, attends social media… and if you attend social media as I attended social media, I found it full of vitriolic hate. One side criticising the other… criticise is a mild word. Really abusing the other. It agonised me. Because the country I had grown up in certainly had its fair share of arguments — people didn’t agree on many matters… political matters, economic matters… — but there seemed to be an unwritten code that we conduct these discussions, these arguments, in a civilised fashion. There have been instances when the pot has boiled over, but now the pot seems to be continuously boiling and boiling over in a very ugly way.

The story of In An Ideal World came to me organically as I thought about the crisis which envelopes not simply our society but our families, our most intimate and personal relationships.

This is what Professor Veena says in the book, isn’t it? ‘There are forces that are setting parents against son, brother against brother, friend against friend. We are becoming unrecognisable to each other’. Is this observation from personal experience?

Yes. I think all of us, including myself, have friends and close family members who are not diametrically apart in terms of their views of what this nation ought to be. Now, it is easy to see this in purely partisanal terms. One can debate and say that this is what the BJP, the ruling party, is saying, this is what the Indian National Congress is saying, the TMC is saying, so on and so forth. But to me, it seemed, this division that one of my characters is referring to in the novel, goes deeper than partisan politics. It’s not simply about the party in power and the party in Opposition. But it is really about a fracture in the soul of our nation and of our citizens. That we have started to distrust each other, be suspicious of each other. We are unwilling to consider the arguments from anyone from the other side. Whenever somebody raises a question, or a criticism against the government, it is interpreted as being anti-national. This is certainly not the climate in which to conduct a proper dialogue about what kind of a nation are we, and what sort of a nation we ought to be.

‘We have started to distrust each other, be suspicious of each other. We are unwilling to consider the arguments from anyone from the other side. Whenever somebody raises a question, or a criticism against the government, it is interpreted as being anti-national’ Ritagnik Bhattacharya

Tell us a bit about the Sengupta family, which is at the heart of this novel…

You know, the Senguptas are very recognisable to me. They are in their early 40s, an outward-looking, progressive, adventurous couple. They are into art, into theatre, into cinema, into politics. They both have jobs in the city — Joy is a bank manager and Rohini is the principal of a private school.

Now, Joy had been an activist in college. What do we mean by activist? A lot of young people, when they are in university, engage themselves in theatre, in writing poetry and in protest. So, he comes out of the crucible of what we generally call ‘Progressive Thinking’. And certainly Joy and Rohini have friends who are also like them.

What comes to them as a surprise and eventually leads to a crisis in the story is when they discover that their one and only child, their son Vivek, who they call Bobby, has a view about life, a view about the nation, which is diametrically opposed to them. He believes in a very aggressive nationalist agenda, he distrusts the liberal views of his parents, and he considers the Hindutva doctrine, an aggressive form of the religion and an aggressive form of its manifestation, to be the saviour of this nation. Thus, the two views clash. Also, the Senguptas find out that something terrible has happened in Bobby’s university and Bobby could be implicated in that terrible affair. That sets up the story.

You have been involved with campus politics — at times violent campus politics — as a student. Are things different now?

That’s a very interesting point that you raise. Because, I think extremism manifests itself in very similar ways, whether it is Right-wing extremism or Left-wing extremism. In my college years, which goes back to the ’70s, I have witnessed extreme Left-wing activism on our campuses. And very similar to the story of Bobby in this novel, there were young people who wanted to do good to society and they were brainwashed to believe in the notion of an armed revolution which led to terror all around. So, there are parallels between the kind of extremism that we see today, which is of one variety, and the kind of extremism that we’ve seen growing up in the ’70s. And that, too, caused very difficult crises within families, within friends and within the universities.

I was a college activist but my politics was never one of extremism. I have always steered away from extremism. And this is not a survival kit but I have always tried to remind myself that a great many number of our citizens are actually very much in the middle of the political discourse, that they want to coexist with each other. They do not want to eliminate the opposition, so to speak. That has been my position consistently in life.

Are today’s youth still guided by idealism?

I think young people of India are of many, many different shades. They are not all of the same kind. Some are driven purely by career ambition. They care two hoots for this society. And there are others who do. What was interesting for me in writing this novel was the level of disconnectedness that many young people today have with the complexity of contemporary Indian life. You know, when the mind is blank, then it is relatively easy to plant an idea, even a dangerous idea. Which is what happens to Bobby. When he grows up in the Sengupta family, he is, in many ways, uninitiated. Because his parents did not want to brainwash him. But when he landed up on campus, this empty canvas was open to the designs of a very crafty recruiter. And that crafty recruiter turned him into the kind of person that he later became.

Where does Kolkata fit in, in this new world?

Kolkata plays its role equally in this division. Again, if one were to look purely at electoral outcomes, one may be mistaken in the notion that one side has won, the other side has lost. But I believe, this is not simply a partisanal difference that we are seeing in our country at this point. The views that were considered to be taboo when we were growing up, really saying ugly things about religious minorities, playing the victim game, have become commonplace in Kolkata. Such arguments are frequently heard in parties, in drawing room conversations, in clubs, and in the streets. So Kolkata has not been spared by the ugly dispute, the ugly differences that we see today.

Kolkata should hold on to its wonderful culture of inclusiveness. The culture of inclusiveness which is in our social life, in the way we conduct ourselves with the people who are not like us. People who may be considered to be the ‘other’. Kolkata should hold on to its culture of negating the other and seeing everybody as a Kolkatan

While you were writing Kalkatta, you had said you had fallen back in love with the city. Is your love affair with Kolkata still on?

I think it is very much on. One loves the exquisite, one loves the ugliness. Because life is like that. We strive for the ideal, and throughout this novel, In An Ideal World, one strives for the ideal, but the ideal is always beyond reach. I think our love, our affection, our attachment to people, to cities, and to everything else is a mixture of the qualities that it brings….

‘We strive for the ideal, and throughout this novel, 'In An Ideal World', one strives for the ideal, but the ideal is always beyond reach’

What do you think Kolkata should hold on to, and what should change?

Kolkata should hold on to its wonderful culture of inclusiveness. The culture of inclusiveness which is in our social life, in the way we conduct ourselves with the people who are not like us. People who may be considered to be the ‘other’. Kolkata should hold on to its culture of negating the other and seeing everybody as a Kolkatan.

What should it reject?

It should reject hasty judgements. These days, when I see many of my friends and acquaintances reading half a paragraph of a book and saying, ‘Oh, I know what this is about. This is just secular rubbish!’ Or listening to someone’s opinion on television and saying, ‘No, no, no, I don’t want to listen to this, this is rubbish.’ Hopefully, Kolkata should adopt a more tolerant, a more lenient culture where we are able to hear each other and form our opinions.

You always have many stories bubbling in your head. What’s next?

Well, a couple of things, really. I have finished a book with my wife Susmita. We are collaborating on a manuscript for the first time, after having collaborated in life for 40 years. This is a book about our journeys through different lands — their cultures, their histories, their art and their cuisines. That book called Moveable Feasts should be out in a couple of months. I have also started work on a new novel, which is not set in Kolkata, it is set in Bombay.

Kunal Basu’s next is a collaboration with his wife Susmita about their journeys together, called ‘Moveable Feasts’ Ritagnik Bhattacharya