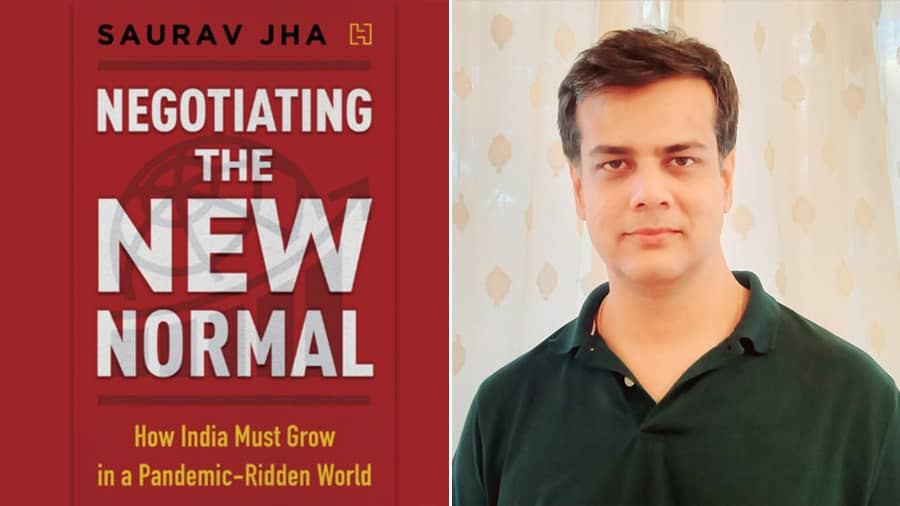

While most literature about Indian economics examines the country as the global nucleus, what makes author Saurav Jha’s latest book unique is how he breaks down major international powers, and seeks to understand India’s place in such a global scenario. Negotiating The New Normal: How India Must Grow in a Pandemic-Ridden World has been receiving acclaim for its detailed examination of declining Western power, the dissonance between US-China, and India’s ripe potential to prosper after the pandemic. In an interview with My Kolkata, the Presidency University alumnus delved into the process of writing the book, how it is different from his previous work and weighed in on India’s economic evolution. Edited excerpts from the interview…

My Kolkata: What was the thought that made you start writing this book?

Saurav Jha: Ever since my days in Presidency College, where I studied economics, the interaction between geoeconomics and geopolitics has been of great interest to me. As I have said elsewhere, the treatment of so-called ‘large affairs’ does not lend itself to a piecemeal approach in terms of outlook. No geoeconomic paradigm arises in a geopolitical vacuum, while national economic interests always inform foreign policy. Negotiating the New Normal was born out of this paradigm and endeavours to analyse the evolving world order before prescribing a role for India in it. This book has sought to do something that is perhaps a little rare in India, in that it looks at the rest of the world for the most part, and then seeks to situate India’s place in it, instead of the other way round.

You started writing this book six years ago. How much did the pandemic change its course?

Yes, the initiation of this effort happened some years before the pandemic and I had to review all that I had worked upon in light of this monumental human tragedy. What I found though, was that the pandemic accelerated many pre-existing trends that date back to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 or even earlier. In that sense, the book continued to write itself with the pandemic bringing about global regime change even faster than perceived initially.

You incorporated both stories and statistics to highlight the weight of the pandemic. How do you straddle between the two, ensuring that readers gain both a subjective and objective perspective?

Well, the statistics lend credence to the story being told. While stories are indubitably important to give the reader a sense of the forces at play, data points sometimes provide a sharper perspective in terms of where things stand. Naturally, finding the right blend is the key to ensuring that the narrative does not stutter in any way. In a book on a subject like this, the two could well serve to complement each other.

Have recent events — the Ukraine conflict, the shadow of economic recession and the struggles of Big Tech, to name some — made you wish that you could add some chapters to the book or write a sequel?

The impending economic recession in large parts of the world is actually one of the things predicted in the book, although the travails of Big Tech feature somewhat obliquely as part of the growing US-China technological rupture that is analysed in detail. The conflict in Ukraine, which in a sense began in 2014 itself with the War in Donbass, does find mention in the main conclusion of this book. That conclusion relates to the inexorable regime change currently underway with a declining West no longer in a position to uphold the neoliberal order of the Washington Consensus, but still incumbent enough to create serious birth pangs for a new multipolar order that is taking shape. Truth be told, ending the book where I did was simultaneously a very difficult and easy decision. Difficult, because there is always a tendency to give more to the reader by weaving in new events into the narrative and in that sense, no book is exhaustive. Easy, because even though the material may be inexhaustible, the writer has certainly exhausted whatever currency he had with family and well-wishers (not to mention his editor) by that point.

Having said that, a sequel to this book is already germinating in my mind and the focus will be on climate politics and global resource competition.

Given recent developments, how do you see the Indian economy evolving over the next decade?

The Indian economy will in all likelihood outperform other major economies in terms of real GDP growth well into the next decade. Although, it must be said that India's potential growth rate, that is, the maximum sustainable rate of growth for real GDP growth, is currently not in the vicinity of 7 per cent as some are claiming, but likely a full percentage point lower. Both India's supply side as well as aggregate demand in its economy have been dented by the shocks of the recent past, and these jolts have hurt the informal sector disproportionately. The challenge for the government is to direct public spending in a manner that increases the economy's overall productivity besides generating a chunk of well-paying jobs which will bolster domestic demand. Aiding the growth of manufacturing will serve both purposes, especially since the servicification of the sector means that its output now supports many more services jobs than in the past. Basically, the government must do all that it can to support an uptick in the private investment cycle that is showing signs of revival after being in a trough since 2013.

Importantly, US-China de-coupling and the West's need to de-risk supply chains in a pandemic-ridden world has created a window of opportunity for an industrial push by India. While the West may reshore certain critical segments of the manufacturing value chain, it will still need the Indian worker to step up in terms of global goods production. Otherwise, inflationary pressures will become entrenched in the Western hemisphere. For its part, India needs to support the rise of consolidated manufacturing supply chains on its soil by spending more on research and development, and seriously supporting the development of medium and small enterprises. If India succeeds in creating deep supply networks, its external balance will also remain ever so healthy by keeping the current account deficit in check and attracting a rising quantum of foreign direct investment.

Any observations on the local economy, especially Kolkata’s, where you studied, lived and keep coming back to? Can regions do anything to capitalise on global changes?

Kolkata’s economy seems to have received substantial support from the IT and real estate sectors since around 2010, although the latter did suffer from demonetisation as was the case across India. Today, there is an attempt underway to develop Kolkata as a regional financial hub and there are indications that this effort will fare reasonably well. In fact, Kolkata is well-placed to tap various higher-end service sector opportunities that are emerging in the current wave of digitisation. But Kolkata also has to serve as a lodestone for manufacturing growth not just for West Bengal, but eastern India in general. For this, the state governments of the Eastern Zonal Council need to work together to create the necessary infrastructure that will complement major central projects such as the eastern dedicated freight corridor. Simply put, Eastern India's hinterland needs better connectivity with its metropolitan centre — Kolkata, even as the city integrates with the rest of the world. With better synergy, eastern India's cheaper human resources can be deployed to outcompete Bangladesh and Vietnam in manufacturing sectors such as textiles, leather and food processing. In fact, West Bengal's jute industry is seeing remarkable growth as the world looks to phase out single-use plastic.

Your three books are on nuclear power, a travel project (with wife Devapriya Roy) and now on the world economy. How different was the writing process for each? Do you prefer writing for an aware and economics-literate audience over writing for the general reader?

To answer your second question first: the intention is always to write for the general reader, but it may not always turn out to be precisely that way. My book on nuclear power (which is used as a nuclear awareness building read by the Department of Atomic Energy) was described as a 'beachside read' by one reviewer, while The Heat and Dust Project (i.e. the book on our travels through India) seems like a novel to some readers. I admit that my book on the world economy perhaps demands more from the reader than earlier works, but then that is the nature of writing itself. Ultimately, a book always finds a writer and by extension a reader.

Saurav Jha’s previous books — 'The Upside Down Book Of Nuclear Power' and 'The Heat and Dust Project'

Does it help to have a wife who is also a writer? Do you take inputs from her?

Without a doubt. Coming from an accomplished novelist who teaches writing at Ashoka University to boot, Devapriya's inputs prove invaluable while structuring a manuscript. She is a master of the craft so to speak and her suggestions do make a difference when it comes to framing a narrative.

What’s next for Saurav Jha? Should we expect a book on defence matters?

Well, yes. My next book is indeed on a defence-related topic. It is a joint effort with Dr V. K. Saraswat, former DRDO chairman and currently member, NITI Aayog. We are writing a techno-economic history of the Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme which laid the foundations for India’s military-industrial sector.