That was a raw deal he got, old man. Master of his realm one day, homeless the next. Surrounded by people all these years, now only the Fool for company. Even his children have kicked him out of home.

The elements too seemed to have conspired against him. Out in the open a storm rages. And it’s raining like hell. “Rumble thy bellyful! Spit, fire! Spout, rain!” Remember the words?

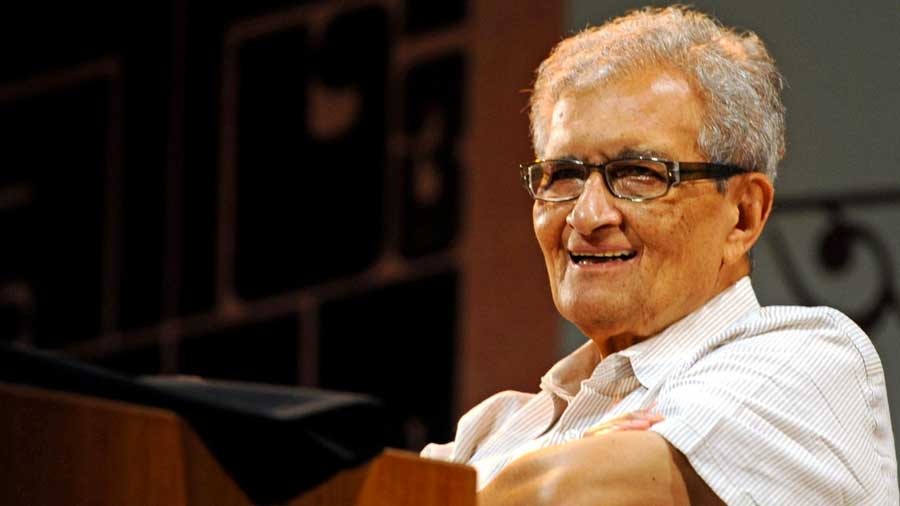

Well, we all know why King Lear ended up like that, a lonely old man who had lost not only everything he had but also his mind. But this is not a critique of King Lear. Rather, it’s an attempt to understand why one of the finest minds of our contemporary world mentioned Lear when asked what book he would choose if he had to recommend only one to the president of the USA.

The one book Amartya Sen would recommend to the president of the USA

Sympathy and solidarity are qualities that people do need: Sen

“I would not like the president to be a one-book person. But if I am forced to choose only one book for the president, it would be hard to leave out King Lear,” Amartya Sen had told The New York Times earlier this month. “I won’t go into an elaborate explanation here, but sympathy and solidarity are qualities that people do need.”

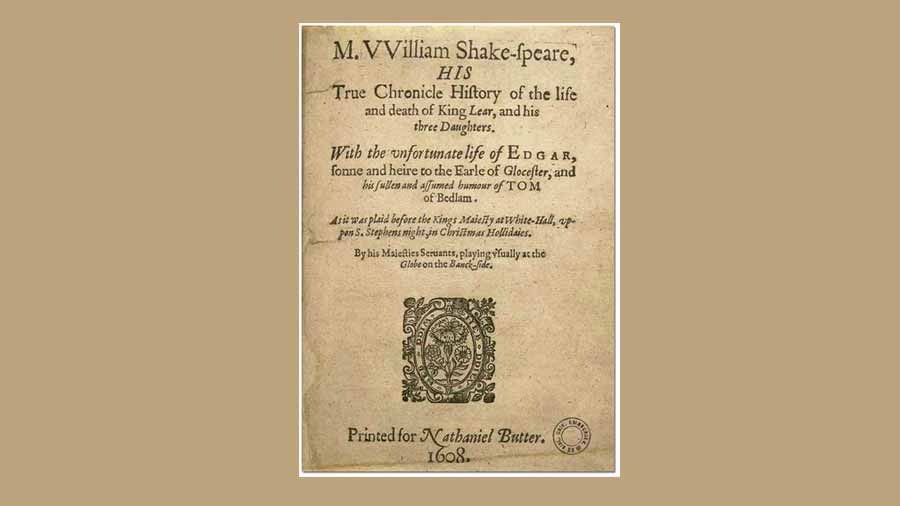

That brings us to the inevitable question: are these the two key words that the Nobel-winning economist thinks can help us interpret the play, one of William Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies, and see Lear’s misfortune in the light of the injustice he has brought upon himself? We can only hazard a guess.

Lear, as allegory and lesson

But before we go ahead, a brief recap. Lear, an ageing king, divides his kingdom between his two older daughters, Goneril and Regan, taken in by their false pronouncements of love, and disinherits Cordelia, his favourite and youngest who truly loves him, because she refuses to flatter her father with insincere comments.

An American stage production of ‘King Lear’ Gettysburg.edu

The two older sisters later go back on their promise and drive out Lear who turns mad and wanders about accompanied by his faithful Fool. Lear later realises his folly, is reunited with Cordelia but the play ends in tragedy as both die. Regan and Goneril die too, one poisoned, the other by suicide, as the complex web of events unfolds through war, betrayal, unimaginable cruelty, deceit and retribution.

Not that Cordelia is entirely blameless; it’s her exaggerated — “and so untender?” — righteousness that lets her down (Act 1, Scene 1). In her stubborn refusal to humour her father, she misses the fine line between tact and bluff.

This, in a terribly superficial sum-up, is the story of Lear, as allegory and lesson — that most great works of literature are.

Mrcchakatika, a moving story of tyrannical rule

But Sen was, perhaps, speaking more as a social scientist than literary critic when he used the words “sympathy” and “solidarity”. Lear’s misfortune, as we shall see, not only marks the endgame of an arrogant ruler; it also serves as a cautionary tale for rulers in general — presidents and presiding priests of state power. In this context, Lear becomes a symbol of a fall from power, bereft of sympathy and people’s support, as canonical literature is used as historical metaphor to score on the side of social justice.

Laurence Olivier as Lear @proffarrior/YouTube

Sen’s reference to a political subplot (a tyrant being overthrown) in Mrcchakatika, a Sanskrit play attributed to Shudraka, is another example of how a literary event has been de-contextualised for the purpose of ethical exigency. Many scholars see the play as representative of various aspects of ancient Indian society, but for Sen it stands out as a “moving story of tyrannical rule, which is ultimately overthrown by a popular uprising, bringing in a more democratic regime”.

The play, Sen says, also airs “some radically new ideas of justice that remain relevant even today”.

The argument that the professor of economics and philosophy at Harvard University puts forward is spread over the entire text of the interview and the references he has drawn underline his preferences; the ethical dimension of welfare economics and his deep concern for the underprivileged, the minorities and the marginal. The references span a wide range, from women’s rights to the malignant impact of segregation by caste and the pro-poor commitments of the ‘invisible hand’, but the thread is hard to miss.

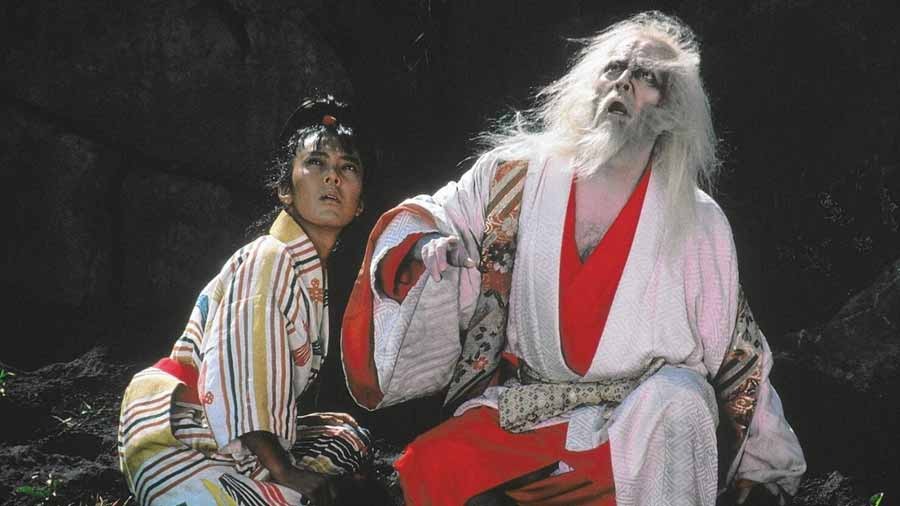

A scene from Akira Kurosawa’s last epic, ‘Ran’, whose plot is heavily inspired by Shakespeare's ‘King Lear’ Rialto Pictures

But for true need… patience I need!

Coming back to Lear, the old king’s journey — from arbiter of individual destinies to impotent nonentity at the mercy of others — packs a powerful socio-political message for every ruler. It’s an authentic message, forged in the smithy of experience, because Lear has seen both sides of power — first as king and then minus his kingdom, deprived of privileges.

It’s easy to get carried away but, for the sake of this essay, we’ll restrict ourselves to a few passages from the play, the focus being on Lear himself and his evolution through emotional turbulence. The first is what he tells Regan (Act 2, Scene 4) after he learns that he would have to do without his promised retinue of a hundred knights.

“O, reason not the need! Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous;

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man’s life is cheap as beast’s. Thou art a lady;

If only to go warm was gorgeous,

Why, nature needs not what thou gorgeous wear’st

Which scarcely keeps thee warm. But for true need

You heavens give me that patience, patience I need!

You see me here, you gods, a poor old man,

As full of grief as age; wretched in both!”

Humans, Lear argues, would be no different from animals if they were satisfied with only the fundamental necessities of life. The passage anticipates Lear’s eventual change of heart and his first step towards the realisation of how precarious deprivation can be. In his loss of choice, Lear understands the shattering penury of the choice-less.

Soumitra Chatterjee as King Lear TT archives

It’s the first stirring of solidarity in Lear, solidarity with the underclass, but it takes him a total loss of privilege to arrive at that realisation. As long as he was in control, he had thought nothing of banishing those who contradicted him — the problem with absolute power; inclusivity extends only to those who concur. As king, Lear should have been more tolerant of dissent.

The next stage of evolution, from sympathy to empathy

Let’s consider another passage, the Fool’s cryptic prophecy in Act 3, Scene 2.

“...I’ll speak a prophecy ere I go:

When priests are more in word than matter,

When brewers mar their malt with water,

When nobles are their tailors’ tutors,

No heretics burned but wenches’ suitors,

When every case in law is right,

No squire in debt, nor no poor knight;

When slanders do not live in tongues,

Nor cutpurses come not to throngs,

When usurers tell their gold i’ th’ field,

And bawds and whores do churches build,

Then shall the realm of Albion

Come to great confusion;…”

The Fool, paradoxical but wise, understands that the world would never be perfect, and the challenge for Lear is to recognise that sage counsel can come from the lowest too. The moment he realises that, he would move on to the next stage of his evolution, from sympathy to empathy, in other words, a deeper solidarity across social and economic binaries.

Anthony Hopkins as Lear in the 2018 film ‘King Lear’

With compassion comes a sense of remorse too

It appears that Lear is already on his way towards that stage. Not long after the Fool’s prophecy, we see a kneeling Lear (Act 3, Scene 4) talking about the plight of the “naked wretches”.

“Poor naked wretches, wheresoe’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these?”

It’s a moment of realisation for Lear, as he recognises how hard life is for the disadvantaged. With compassion comes a sense of remorse too — that he did nothing for the underprivileged when he could have.

“O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this. Take physic, pomp,

Expose thyself to feel what the wretches feel,

That thou may’st shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just.”

He comes up with a bitter remedy: exposure to suffering so that those who are privileged understand what is necessary and pass on the excess (“superflux”) to those who are deprived. That would be justice.

Social awareness has come late, too late for any scope of redress in Lear’s lifetime, but the message is unmistakable. It’s important for people, especially a king — the ruling class as a whole — to have the qualities of sympathy and solidarity.

As the scholar from Tagoreland has reminded us again.