The biggest applause at the closing ceremony of the Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF) was for the lady who took home the Royal Bengal trophy for Best Director in the international competition. The reason was apparent. Virna Molina took the stage in a blue-and-white Lionel Messi jersey, accepting the award for herself and her husband Ernesto Ardito. For a Kolkata audience, still rejoicing in Argentina’s World Cup triumph four days ago, seeing the trophy in the hands of Messi’s compatriot was a heart-warming sight.

“When my name was announced, I slipped on the team jersey. I wanted to feel close to my countrymen,” said Molina.

Virna Molina poses before a banner at Nandan Picture: Sudeshna Banerjee

She had the jersey on also when she was passionately cheering her team at a screening they were invited to on the night of the final by the KIFF authorities. “I went along with two other directors. One was Portuguese and another Romanian. Since they stay in Paris, they were supporting France.” But of course the majority of the spectators were rooting for Molina’s team.

The biggest high was watching the wild celebration on the streets on the way back to the hotel. “I am never going to forget the experience in my life. I wanted to get out of the car and join them but the official accompanying us refused. I posted a video of the celebration on social media, with the comment that this was not Buenos Aires but Kolkata!”

She was aware of an Argentine fan base in Bangladesh but not so in Kolkata, which she knew as the city of “Madre Teresa” and as the cultural capital of India. “I saw so many flags of my country in the streets when I arrived. It was amazing!”

A still from the film Hitler’s Witch

The film which won big in Kolkata, Hitler’s Witch, directed and produced by the couple, is about a young woman in ’60s Argentina. Her mother was one of the women who controlled a concentration camp and tortured prisoners for pleasure. Years later, she killed herself. Her daughter, the film’s central character, looks like her but neither shares her beliefs nor knows much about her mother’s Nazi past. The plot centers round a Nazi family’s arrival in her house. “It is a fictional story. But after World War II, many Nazi families took refuge in Argentina, especially Patagonia, where they had support, and spent lives like normal people.” Molina points to the presence of about 500 detention camps in Argentina during the military dictatorship between 1976 and 1983. “In those camps, Jewish prisoners were tortured more than the rest. Buenos Aires and its suburbs alone had around 20. Over 30,000 people vanished from these camps.” The biggest of those, Esma (Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada/Navy Petty-Officers School of Mechanics), is located close to her home. “About 5,000 people were detained and tortured there. Barely 150 survived,” she says.

The film also talks of the situation of women in ’60s Argentina. “The Nazis believed that the biggest function of women was reproduction.”

The phantom of Nazism still looms, in Argentina as elsewhere, she says, mentioning a far Right leader, Javier Milei, in her country who, paradoxically, supports economic neoliberalism. “The football team does not support such views. Of course, they do not speak but they do things that speak for their liberal stand.”

After the World Cup triumph, Messi, she says, is more powerful than the country’s President. “He is so friendly, so human, so honest, so simple in the best way.... He has so much money. He could be horrible. But he treats his wife as equal. He understands friendship and family. Many footballers of the earlier generations did not have these values,” she says.

The team itself, she feels, is feminist, if feminism is the opposite of patriarchy and oppression. “The players respect women. They cry when they are sad, unlike Rightists who believe men should not cry. Such actions send a message to young people, some of whom support far Right parties. The football team is bringing about a change in society for the better,” she says.

Molina was three years old when Argentina, still under military dictatorship, first won the World Cup, in 1978. But she has memories of the 1986 World Cup victory and Diego Maradona. “Four years before that, in 1982, we were at war with England over Malvinas (Falkland Islands). When he was running (on the field), it was as if all the Argentine people were pushing him — “go, go”. Nobody could stop him. That second goal (in the quarter-final against England) was…,” she breaks into laughter while talking of Maradona’s controversial “hand of God” goal. “It was beautiful revenge. Football sometimes is like poetry.”

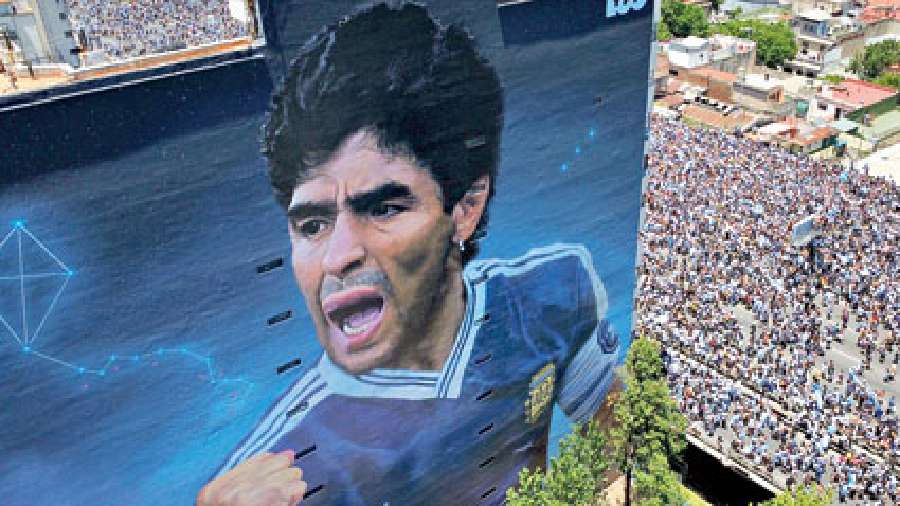

A mural of Diego Maradona looms over a victory parade after winning the World Cup in Buenos Aires on December 20 Reuters

But this World Cup is even more special. “After Covid, it was very hard for us. So many died, so many lost their jobs. This victory brings us cheer and happiness. This is a beautiful gift. We have started to believe in ourselves again.”

Football, she points out, is what connects Argentina with the world. “Every time I mentioned Argentina, people in Kolkata had a smile on their faces and mentioned Messi.”

Molina walked around a lot and travelled by Metro during her stay, going to the flower market and St. Paul’s Cathedral. “The ruins of the British Empire are like phantoms all around. That was in the past but now this is your city to recreate. I got that sense in many places. Except at Victoria Memorial.”

Her next project might bring her back to India. “I am writing one, titled Jesus X. There is some research that says Jesus came to Kashmir with his mother to study with masters of yoga. If it happens, I will shoot in Jerusalem and Kashmir.”