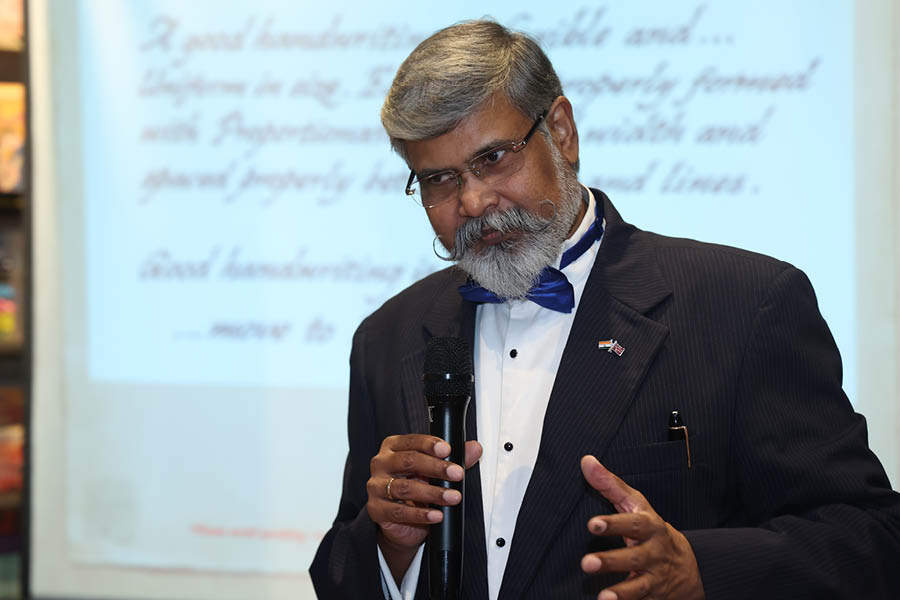

Kambam Chakrapani Janardhan is a man of many talents. He is best known for his expertise in handwriting and calligraphy, but he is also an anthropologist, author, artist, aviator, corporate trainer, entrepreneur, geographer, mimicry artiste, marksman, orator, and educational, social and political reformer.

Born and based in Bengaluru, Janardhan, 62, is the founder of India’s first museum of handwriting, named J’s La Quill Museum of Handwriting and Calligraphy, in his home city, and a professor of management and penmanship in some of the city’s leading private universities. His passion has taken him across the world, with speaking assignments at several prestigious institutions, including Oxford University.

During the 1980s and the ’90s, when Indian passports were still written by hand, the handwriting deployed for the document wasn’t pleasant to look at. In 1993, when Janardhan applied for his passport, he submitted a letter to the passport office requesting to write his own passport so that he could “project the decorum of this country to the highest capacity” wherever he goes. After viewing his penmanship in the handwritten letter, he was given the green light by the officials. Janardhan could well be the first civilian in the world who wrote his own passport, using it to travel across the world, from Singapore, Thailand and Hong Kong to the UK and the US. He used his handwritten passport for 10 years before the passport making process was mechanised. Apart from his passport, Janardhan has also handwritten his daughter's birth certificate and his father's death certificate.

During a recent visit to Kolkata, Janardhan spoke to My Kolkata about the importance of handwriting, a “personal approach” to teaching it and more.

The downfall of good handwriting

Janardhan began by pointing out how “we all are a product of a faulty system of education when it comes to writing”, as the cursive that is usually taught in elementary schools is the “downgraded version” of the original form, brought into India by the British when they implemented the Macaulay education system. This was called the Copperplate system of writing, intended to be written slowly with a flex-nibbed ink pen.

However, in the contemporary world, where efficiency and speed are of maximum importance and “one does not have the luxury of taking days to pen down words, the beautiful lines of Copperplate writing have devolved” into indecipherable scribbles on exam sheets.

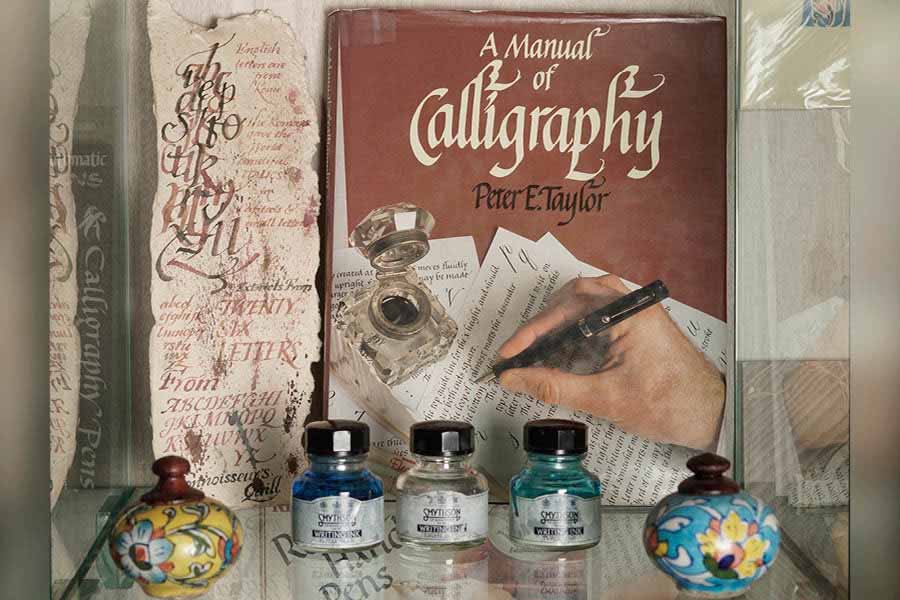

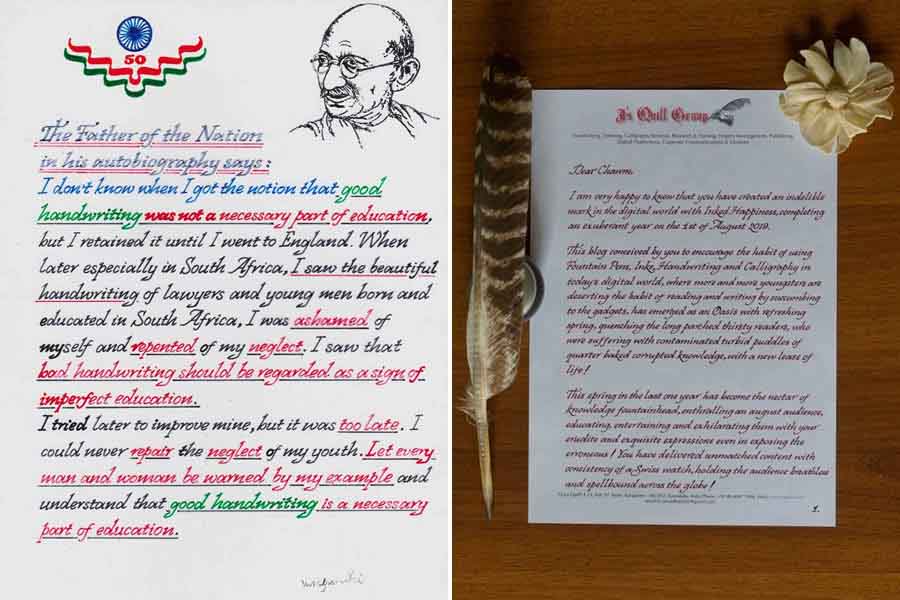

Items on display at Janardhan’s museum in Bengaluru

Janardhan believes that the inability to communicate one’s thoughts finds direct links to the butchering of handwriting, as the written word is often rendered illegible due to time constraints. Expressing his concern for modern society’s overt dependence on technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI), he mentioned: “Technology is important, but one should not become a slave to it.” He added that the propensity to type, instead of write, has led to a “short-circuiting of communication”, with students of different competencies succumbing to the use of ambiguous short-forms and contractions instead of proper words.

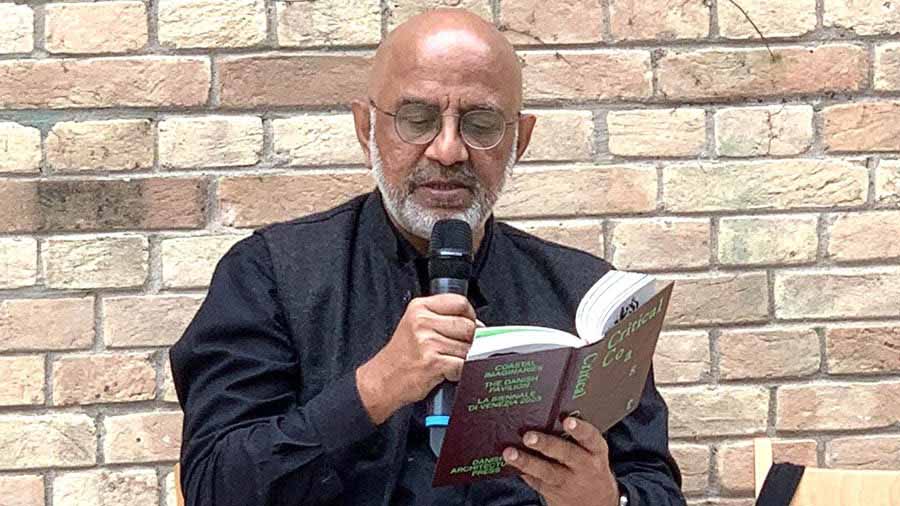

‘Our brain is the hard drive… our hand is the printer’

A couple of examples of Janardhan’s exquisite handwriting

While speaking about the teaching of handwriting, Janardhan explained how it has become somewhat of a “lost vocation”, as most parents and teachers today recommend run-of-the-mill handwriting books, which prove to be ineffective, since every individual has a separate capacity and cannot process the repetitive copying involved in perusing these books.

To illustrate his point, Janardhan used the metaphor of a computer — “our brain is the hard drive, absorbing the information, whereas our hand is the printer, with its cartridge being the instrument of writing. Since everyone has a different hard drive, the transmission to the printer will differ naturally, which is why a personal approach to teaching handwriting is the need of the hour”. According to Janardhan, “the average human is able to write 18-20 words per minute” and this limit is grossly ignored in most examinations, where students are expected to write double or triple the amount than is possible by the average person, thus leading to poor handwriting.

The normalisation of such handwriting by educators is another deep flaw in education systems across the world. “Knowledge about handwriting leads to an awareness and understanding of several issues such as dyslexia, dysphoria, writer’s block, learning disabilities and more, which are all treatable issues with the correct methods of teaching,” clarified Janardhan.

Creating ‘alphabet mechanics’

‘Write to be read, not to be misread,’ reminds Janardhan

Janardhan teaches handwriting via logical exercises he has developed himself. He believes: “Writing is a pleasure. Beautiful thoughts are unravelled through writing. So, the writing itself should be beautiful.” In fact, instead of calling his classes handwriting courses, he calls them “alphabet engineering programmes”, where students manufacture small exercises to create good handwriting. Even if an individual loses their footing in the process, their basic knowledge is thorough and they can fix the issue themselves, thus becoming “alphabet mechanics”.

Along with a focus on handwriting, Janardhan also emphasises on the importance of language and the fact that all languages look and sound mesmerising when spoken or written in the way they were originally meant to be. Showcasing his imitation of accents (with a British example), he said, “There is nothing wrong in speaking English like an Englishman.”

Janardhan feels that governments should promote awareness about communication through handwriting. As someone whose motto is “write to be read, not to be misread”, he has no doubt regarding the importance of implementing proper handwriting methods that can be taught at all levels of education. Only then can one hope for a revival of the quintessential beauty of language and all that it entails.