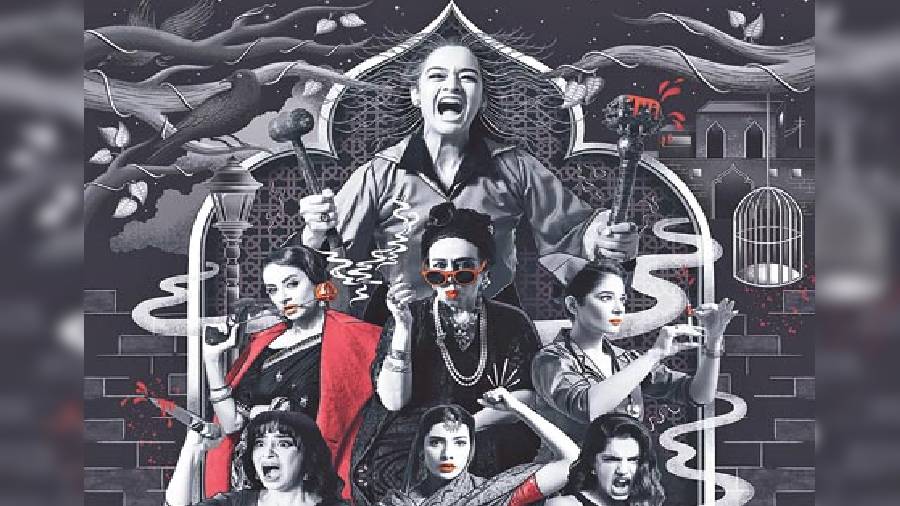

Please mention my school name,” Meenu Gaur requests The Telegraph before logging out of the video call. The Ashok Hall girl, whose last film was Pakistan’s first entry to the Oscars in 50 years, talks about Qatil Haseenaon ke Naam, her web series on femmes fatales, that dropped last Friday on Zee5.

You are a Kolkata girl, right?

Yes, I grew up and went to school in Kolkata. I was very active in extra-curricular activities, especially theatre, while I was at Ashok Hall. The city, my school and those years have been a big influence on me and my work. I left for college in Delhi — Lady Shri Ram College for Women and MCRC (Mass Communication Research Centre) Jamia Milia for my film degree — and went on to do PhD at SOAS (University of) London. I have been living in London for more than two decades now.

Meenu Gaur

Do you visit Kolkata now?

I did attend the Kolkata International Film Festival in 2013 with my film Zinda Bhaag but I never went back for a proper visit. My buddies have been making plans every year to come for Durga Puja. But it hasn’t happened.

Zinda Bhaag was Pakistan’s first Oscar entry in decades, right?

Yes, in 50 years. Zinda Bhaag is in Punjabi. The film’s co-director and co-writer Farjad Nabi is from Pakistan and is a long-term collaborator of mine. I have pan-South Asian influences. I grew up speaking Bengali, my parents are from north India. For several years, we moved to Sri Lanka. Now I live in London. Here the South Asian community collaborates a lot. That continues in my work.

Zinda Bhaag had another Indian link in the form of Naseeruddin Shah along with the Pakistani actors in the cast.

Yes. He is like a mentor. I have kept that relation with him.

What is the basic premise behind Qatil Haseenaon ke Naam?

I was working within the film noir genre. The concept I had was that villainous women, or vamps, have always been seen through the male gaze and we are told they were dangerous and beautiful and one should stay away from them. I thought what if the story is told through their eyes. The story completely changes.

How are the episodes divided?

I asked myself what could the motives be for which women would kill or fight. So each episode has a theme — love, duty, passion, justice, revenge and revolution. It is like an anthology. Every episode has its own story. But there is a connecting thread running through all of them, which you get to know in the last episode. There are seven characters whose stories are told in six episodes.

You got an ensemble cast. Sanam Saeed, for instance, is known in India for being part of the Fawad Khan-starrer Zindagi Gulzar Hai.

We tried to cast actresses who embody the essence of the particular character. Sanam plays a character called Zuvi, who is sassy, playful, unapologetic, quirky and fun. For me, Sanam embodies that. Then there’s Sarwat Gilani, Meher Bano, Faiza Gilani....

Who is the oldest among them?

We were conscious to break the male stereotype that femmes fatales have to be young. We have two older women who are qatil haseenas and lead their own episodes in Samiya Mumtaz and Beo Rana Zaffar. Femmes fatales, in my view, are women who know what they want and they will go and get it. That is enough to make them a threat in male eyes. These characters are all women who have had a promise betrayed or who want to correct a wrongdoing.

When did you shoot?

Absolutely in the midst of the pandemic! We finished shoot in March. It took place in three different locations. We had to shift a lot to get the spaces we wanted. We wanted to do noir but we are calling this desi noir. Noir is such an Westernised genre and it has been seen mostly in Hollywood. What would it look like if we did it in a south Asian context? It was quite a challenge to shape that aesthetic. Our choreographer Mo Azmi tried to craft this language. We wanted old havelis and old spaces, like you have in the older part of Kolkata. It is kind of a mythical space in contemporary age but stuck in time, called Andhrooni Shahar, with bylanes which sell only musical instruments or exotic birds. People who live in crumbling mansions there may live in a modern city but there is a distinct difference in their lifestyle. We went to Lahore, Karachi and some small towns in the outskirts.

Perhaps your next film will be shot in Kolkata.

I am actually looking forward to it! There is a lot of Kolkata and my growing up years in what I do and how I do.