Today is Khordadsal, the birthday of Zarathustra, prophet of the Parsi community. But the Parsis, they say, are a dying community. We have heard this over and over again. But why are they dying, and what factors have contributed to their gradual disappearance?

First the facts. In the 1951 census, we were 1,11,791 and in the 2011 census we were 57,000.

As veteran Supreme Court advocate Fali S. Nariman has said, “A proud boast of Parsis is that they belong to the world’s most ancient monotheistic religion. As a matter of fact, they do. But presently, with the steep decline in birth rate, the entire community is in jeopardy; it is believed, by many, that Parsi personal law is largely responsible for this plight.”

What is this personal law?

Most Parsis mistakenly believe that an obiter dictum (an observation) made by a judge in 1905 to be their personal law. The father of J.R.D. Tata, Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, had married a French Christian lady and converted her to the Parsi religion. Their marriage was performed under the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act. The question of conversion was then debated in court. During the proceedings of the case the question of the acceptance of illegitimate children of Parsi men and women with Parsi and alien partners also became the subject of debate. An expert committee on religion was appointed. They were of the opinion:

- Conversion was a tenet of the religion.

- Child of a Parsi mother is a Parsi. Being born of a Parsi mother’s womb there was no doubt to the parentage.

- Parsi men did not have this advantage of automatically proving the parentage of their illegitimate children (there were no DNA tests available at that time) and finally the court had to give the stamp of approval for their acceptance of these illegitimate children. The judges tried to differentiate the words Parsi and Zoroastrian claiming that Parsi meant race or caste and Zoroastrian meant religion.

The navjote ceremony of Prochy’s three grandchildren, through which an individual is inducted into the Zoroastrian religion. Reproduced with permission from 'Who is a Parsi?' by Prochy N Mehta, published by Niyogi Books

This judgement was considered as an obiter even in 1936 when the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act was promulgated. The Act defined Parsi as a Parsi Zoroastrian and also stated that one could cease to be Parsi by conversion to another religion. Obviously, caste or race were not considered in this Act when defining a Parsi, as one cannot cease to belong to race or caste.

Why does this judgement of 1905 which accepted illegitimate children have an affect on the decline of the Parsi population today?

The laws of the land changed

Until 1954, there were no inter-religious marriages in India. All marriages were under personal law. A Parsi married a Parsi or a Hindu married a Hindu etc. Or they could give up their religion and marry under the Special Marriage of Act of 1872.

The Special Marriage Act of 1954 allowed the spouses in an interfaith marriage to marry for love and keep their faith. It was a revolutionary law at that time. Marriage was a duty, a bond between two families for reasons not involving love and romance. The Nehru government decided that “the time has come when religious differences should not stand in the way of a couple getting together, if they feel that their lives are cast together, and the fact of their marriage should not in any way affect their religious beliefs.”

Parsi intermarried men found salvation in the obiter dictum of 1905, which gave a legal sanction for acceptance of their illegitimate children to mean acceptance of their now legitimately possible children.

Parsi women, whose children have been accepted by religion, custom and tradition, did not have this express legal sanction. In my book Who is a Parsi? I have printed photocopies from the original judgement obtained from the Privy Council archives.

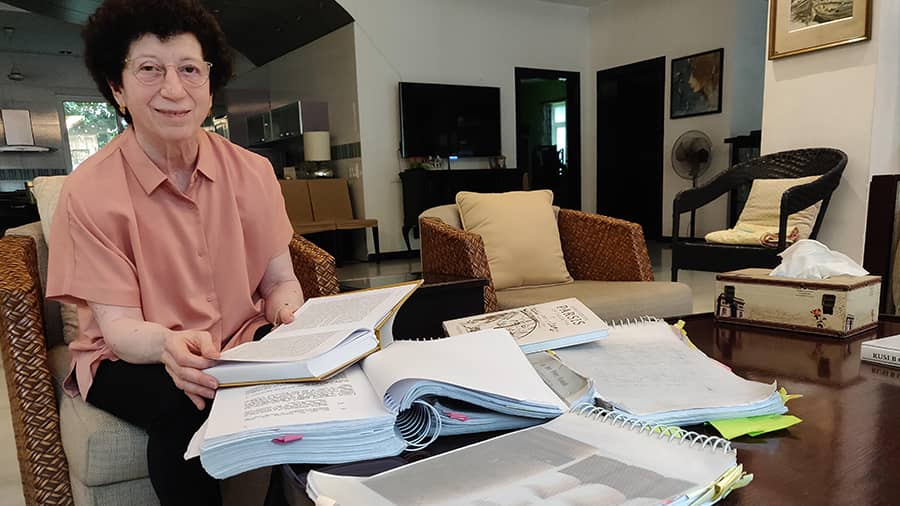

Prochy with the photocopies from the original judgement obtained from the Privy Council archives Karo Christine Kumar

We now have court records showing the views of the expert committee on religion regarding the acceptance of children of Parsi women with Parsi or other men. These records should re-establish for intermarried Parsi women equal rights of acceptance as Parsi men enjoy.

As interfaith marriages for women are not being accepted, a huge percentage – more than 20% of women – do not marry. In addition, 50% of marriages are interfaith. In effect, 25% of the future generation are being rejected.

An ageing population, low birth rate, refusal to marry and rejection of a full quarter of the future generation is seeing the Parsi community racing headlong into extinction.

Prochy N. Mehta

Prochy N. Mehta is an Asian record holder in sports and also the first female president of the Calcutta Parsee Club. She is actively involved in several companies including the business started by her father Rusi B. Gimi, eminent social worker and pioneer in outdoor advertising in India.

'Who is a Parsi?’ by Prochy N. Mehta, published by Niyogi Books, is available at Starmarks across Kolkata and on Amazon.