Half an hour before he died on October 6, 2017, Monojit “Kochu” Datta, the man who made Latin music cool decades before urban India became hip to salsa, was impersonating a showboat boxer.

Wearing red shorts, torso bare, he was flexing biceps, throwing punches in the air. He was happy, it is evident from the video.

He was ready to go soundcheck for a gig at a Delhi jazz club with his band, Monojit Datta & The Orient Express. A band he had conjured out of thin air two decades ago. That is how I would like to remember Kochu da, as he was to all of us whose lives he changed.

Because if there is a word that describes Monojit Datta, percussion wizard, multi-instrumentalist, guru and person, it is conviction. He lived and breathed Latin music. And perhaps we can just be thankful that he died doing what he loved.

He was one of his kind among a billion-plus people. He was the first genuine Latin percussionist in a country that often sways to substandard imitations of Latin rhythms.

He was one of the people who make Kolkata unique. And he would have been 59 years old today, September 3, 2021.

D for Brother, Kochu da's band with his cousin, guitar guru Amyt Datta, opened the doors of perception for a generation of Calcuttans like me in the early 1990s.

When Western music meant We don't need no education, D for Brother concerts — at the G D Birla Sabhaghar, Kalamandir, Gorky Sadan, Max Mueller Bhavan — were like universities of other-worldly sonic landscapes.

Kochu da used to have half the stage for his instruments, which included vacuum cleaner pipes and steel dinner plates. You can listen to the only D for Brother album that was released by clicking here.

I started learning guitar from Amytda. The Datta brothers's house then, opposite the St James school and next to Alimuddin Street, was where a bunch of us virtually became responsible adults from bumbling teenagers. It was our gurukul.

We became ready roadies for D for Brother; it was musical education of the highest order. And after D for Brother fell apart, as bands always do, Kochuda chose us, a few of his and Amytda's students, to do what he had always wanted to do: Make an authentic Latin music outfit.

There was a small problem. None of us really knew what that meant. But Kochu da could teach a donkey to play salsa. He would sing out everyone's part — “Bumpy, you play pak-ghung-ghung, ghung ghung. Sumit, you play tingcha-tingcha tingcha cha tingcha” and so on — in an 11-piece band.

All we had to do was execute it. We went through a rigorous training regimen of many months: Practice, then listening sessions (with Kochuda playing LP after LP of big-band music), practise again, rinse, repeat. He hand-held us through the egg-down-the-slope cascade of every Latin rhythm, be it cha cha cha, tango, guaguanco, samba, bossa nova...

Thus was born Monojit Datta & The Orient Express. Since then — 1997 — the band has undergone many line-up changes, gigged across India, and its alumni are spread across the country's music scene.

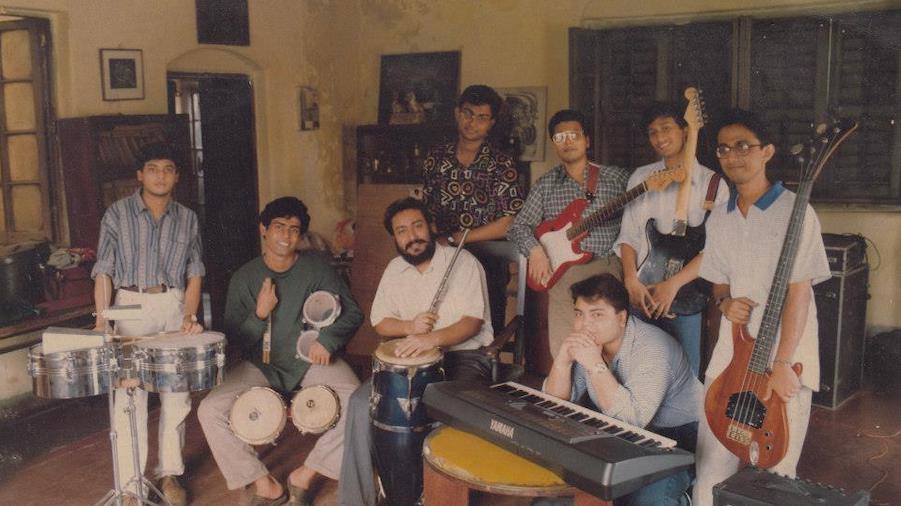

The first line-up of Orient Express. From left, Sanjay Gupta, Dwaipayan Saha, Monojit Datta, Sourav Chatterjee, Sayantan Sengupta, Sumit Bhattacharya, Mainak Bumpy Nag Chowdhury and TL Mazumdar (seated) Arranged by My Kolkata

Kochuda taught us to be fearless. From John Coltrane to Weather Report, we would drag everything down to Afro-Cuban territory. I remember The Telegraph Metro covered a gig we did for the farewell of the then US consul general in Kolkata— and to read the piece we had to get a dictionary to decode phrases such as “encomiums followed for the band” — in which the reviewer wrote: “... even Beethoven was not spared, smilingly”.

In hindsight, it seems incredulous.

One man in Kolkata wants to create a "scene" for Latin music, confident that not only will it survive but catch on. One man, who can play with any musician in the world, choosing a bunch of total greenhorns and grooming them. And all of it falling in place. Buena Vista Social Club in Kolkata, almost.

Only Monojit Datta could have pulled that off. He was a force of nature.How else do you explain learning the intricacies of Latin music before the days of instant flow of information?

He was so authentic that foreign musicians — even those for whom the novelty of desis playing Western instruments with élan has long worn off — would always be taken aback. A guitar player from India is no longer unique, but a true conguero like Monjit Datta still is.

There are very few musicians in Kolkata who did not learn either from Monojit or Amyt Datta.

Kochu da was almost a yogi; one with a wicked sense of humour. Once we were playing December 31 night at one of those snooty colonial-era-relic clubs of Calcutta and the manager was giving us gyan at soundcheck about how we must be propah in our dressing for the night.

When he was gone, Kochu da said: “Just wait for the night to end.” When we were heading back home in the first light of a new year, the manager was sleeping, the end of his tie in one of the buffet trays.

I know Kochu da liked me immensely; but anyone who knew him will say that, and truthfully so. Kochu da was such a warm person that everyone felt special around him. Even while playing a jaw-dropping drum solo, he would mostly be smiling beatifically at you.

Kochu da never came across as bitter, though he had enough reason to be. He was always positive, always laughing, no matter how grim the situation may be.

One particularly hot day in the initial days of Orient Express, when energy levels were low with no gig and no assurance of one in the near future, Kochu da walked in for rehearsal and said: "Let's make a new tune and call it Hard Times. Sumit, Bumpy, Wreju, Kallol, you have to play this in unison."

And then he mouthed out a frenetic melody. (Here is that tune)

That was his mantra: Just put your head down and have fun working on your art. Don't bother about anything else, that chaos can and will sort itself out. Whenever someone came to him for advice, he would say: "Keep at it, and remember you are playing for god."

From starting out with bands like New Blues Connection to rocking out across the country with Shiva in their heyday in the 1980s and 1990s to sharing the same stage as Santana at the Java Jazz Festival in 2011 (with another Latin-jazz band he founded later for a brief while, Los Amigos), Kochu da blazed many a trail, but I am thankful that I got to observe from such close quarters the two projects that defined him: D for Brother, and Orient Express.

And I'm grateful to have been touched by his light.

(This article first appeared on Rediff.com)