For the well-travelled Subrata Basu, 64, it is easier to recall the places he has not visited in India than the ones he has. “Except for Ladakh and Kashmir, I’ve more or less been everywhere for work,” says Basu, while relaxing at his familiar haunt at the Royal Calcutta Golf Club (RCGC). An engineer for more than four decades, Basu has been witness to India’s economic and industrial journey from Syndicate-era socialism to a free market democracy, from a country where big bridges and buildings were a metropolitan rarity to a nation where everything is getting “sleeker, faster and better”.

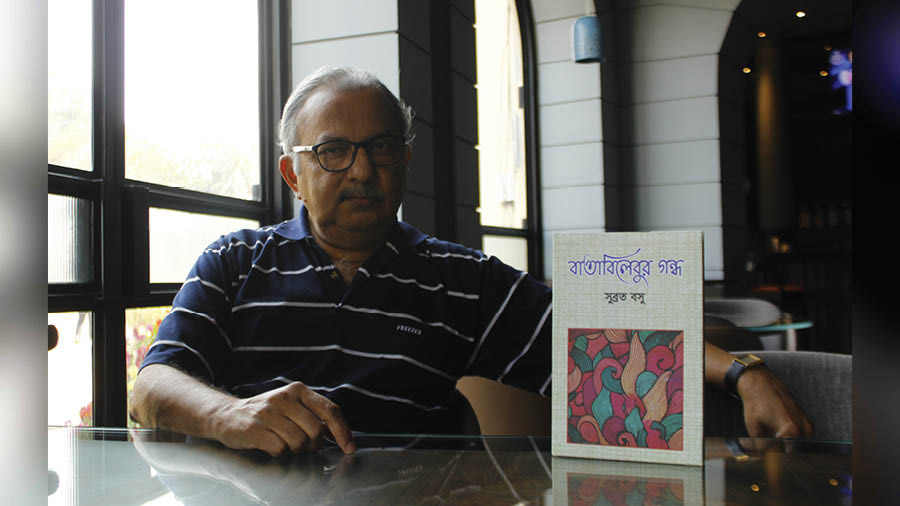

Born and brought up across a series of “cosmopolitan and diverse neighbourhoods” in south Kolkata, Basu studied at South Point High School and then at the Indian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology in Shibpur (known as the Bengal Engineering College during Basu’s time). For the better part of his life, Basu had not written anything original, barring a small diary where he would note a thought or two, confident of elaborating on them years later. When Covid-19 struck, some two years after his formal retirement in 2018, Basu’s time for elaboration had arrived. The result was a wholesome book of short stories and personal commentaries, intriguingly called Batabi Lebur Gondho. The stories are in Bengali apart from a couple of English ones. Released last July and re-published with updates in time for the recently concluded International Kolkata Book Fair, Basu’s debut work provides a kaleidoscopic perspective of the so-called ordinary life in India. For someone who admits that “my values are guided by my emotions”, the book is also an attempt to help Basu process his feelings.

Meeting a friend after 30 years who never forgot Basu or what he loved

The titular story of the book is about Ramchandra, who served as a domestic help at the Basu household while he was growing up. A few years apart in age, Basu and Ramchandra became quite close, before the inevitable separation happened. “He had to leave to make more money to start a family of his own,” says Basu, who would send money orders for years on behalf of his friend to Ramchandra’s loved ones in a village in Muzaffarpur, Bihar. Then, one day in 1997, while in Bihar for a project, Basu decided to pay his friend a visit, having not seen him for more than 30 years.

Without Google Maps, Basu’s seemingly interminable walk threatened to lead him astray, but he eventually found Ramchandra. “When I saw him, he looked as if he was 20 years older than I was. He had lost a part of his vision due to cataract, could barely walk due to a snake bite and lived in miserable poverty,” narrates Basu. But Ramchandra’s limitations did not prevent him from treating Basu like royalty, as the two friends rekindled old memories for a few hours before Basu had to bid adieu.

“Stay back for some more time,” urged Ramchandra. “I can’t, I have to leave. But I can meet you near the highway tomorrow on my way back,” replied Basu. The following day, Basu saw Ramchandra standing by with a small bag in hand. After Basu handed Ramchandra a crutch bought en route, Ramchandra gave Basu a sum of Rs 100. “It’s for your son” was the explanation. But there was something for Basu, too. A bagful of batabi lebu (pomelo). “He still remembered how much I used to love batabi lebu growing up. It brought tears to my eyes,” says Basu.

‘For the longest time, I just wanted to know what a good toilet looks like’

Professionally, Basu enjoyed his time in Punjab and Gujarat the most Sourav Nandy

Many more moving stories abound in Basu’s book. From how a vegetable seller in his locality struggles to decide between paying for her daughter’s cancer treatment and feeding the rest of her family to how a dog Basu came to know on a trip saved him (and his boat) from potential disaster. Neither showy nor sentimental, Basu’s prose is suave and subtle for the most part, occasionally making room for a hint of social satire.

One such example is another account from real life that has been touched up slightly for readability. It features a porter who had come as part of a shifting assignment at Basu’s neighbour’s house. In charge of the operation in the absence of his neighbour, Basu received a simple request from the porter once the job was done: “Can I use the washroom?” Basu obliged without hesitation. Once the porter came out, he thanked Basu no end. “In all my years of packing and moving stuff, nobody has ever let me use their toilet. They always ask me to go out and use the public toilet. For the longest time, I just wanted to know what a good toilet looks like,” said the porter, who expressed his gratitude to Basu and assured him that “I’ll be there whenever you need me”.

Moving around the country and figuring things out by himself had taught Basu the importance of humility and kindness from a young age. As part of his professional journeys, he enjoyed his time in Punjab and Gujarat the most. “If I have to choose one state to represent my country, it’d be Punjab. The people there are not only among the most hard-working but also the most large-hearted,” says Basu, who is also full of praise for the entrepreneurial ingenuity of Gujaratis: “The best thing about their culture is that no matter their pride or privilege, they learn everything first hand. You can be the son of a magnate who has a paints business, but when you start off, you have to go and learn the work that your lowest-ranked employee does by doing it yourself.”

‘The highlight of my career remains… the Second Hooghly Bridge’

Basu was a key member of the team that built the Vidyasagar Setu TT archives

When it comes to his most satisfactory accomplishment, Basu brings the focus back to Bengal and Kolkata. More specifically to the Vidyasagar Setu (also known as the Second Hooghly Bridge). “Throughout my life, I’ve helped build bridges, dams, power stations, steel plants and oil refineries. But the highlight of my career remains my work as part of the team that created the Second Hooghly Bridge. It was intense and rigorous labour that saw me toil from 7am to 10pm on most days. There were times when I had to stay back all night. Finally, when the bridge was inaugurated (in October 1992) and I got to shake hands with P.V. Narasimha Rao (then Prime Minister of India), my heart swelled with pride. Even today, whenever I cross the bridge, I can’t help but think of the foundations, the cables and the other details that went into making the structure,” explains Basu.

Currently serving as a consultant for Hutni Projects, a Czech company whose India office is located in Kolkata’s Sector V, Basu aspires to write novels and transition into a full-time author. A classical music enthusiast who takes to the golf course once in a while, Basu is presently researching the impact of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on the local community and habitation. “I want to study how the construction changed people’s lives as well as the state of the place. Sometimes something big happens and people forget about the small tremors that occur in its wake. For me, those small events matter, for they tell a much larger story,” believes Basu, whose solitary message for his readers is: “Everything you’re searching for is around you. Don’t just look, but learn to observe”.