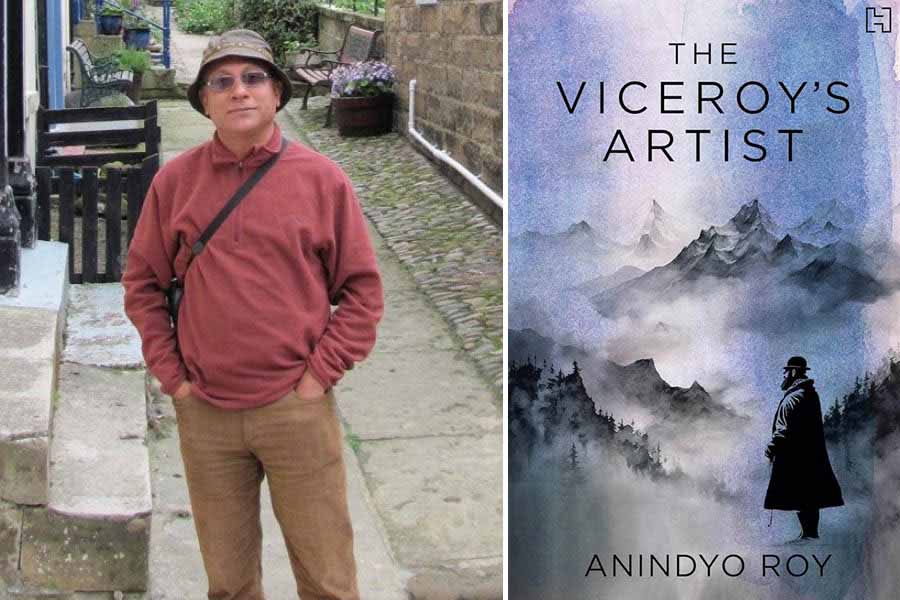

The image of a tall, bearded gentleman from yore standing against the unmistakable outline of the Kanchenjunga rising up from a misty middle ground draws one in immediately. Such is the captivating cover of The Viceroy’s Artist (Hachette India), a novel by academician and author Anindyo Roy. This fictionalised, inner-world narrative is one that explores the thoughts and stories of Edward Lear, a notable 19th century English artist, poet and traveller.

My Kolkata spoke to Roy, associate professor emeritus at Colby College in the US, about his book, Lear’s life and the similarities and differences between the two. Edited excerpts from the conversation follow.

My Kolkata: Before we get to the book, why do you think Edward Lear’s travels in India have not merited more studies or stories?

Anindyo Roy: I discovered during my research that many of Lear’s scholars don’t even cite his India travels and, when they do, the travels are dismissed in a few passages. Also, his Journals may not have received critical attention because, unlike his other travel writings, they are too fragmentary, and appear as mere cursory notes made hastily during the trip. Therefore, they didn’t warrant any sustained critical study. In fact, that was one of the reasons that made me turn to fiction.

On another note, The Edward Lear Society (based in the UK), whose president Derek Johns provided one of the first endorsements of my novel, is currently assisting me to get the novel published in the UK.

An inner journey marked by his own sense of encountering the unfamiliar and dealing with the unsayable

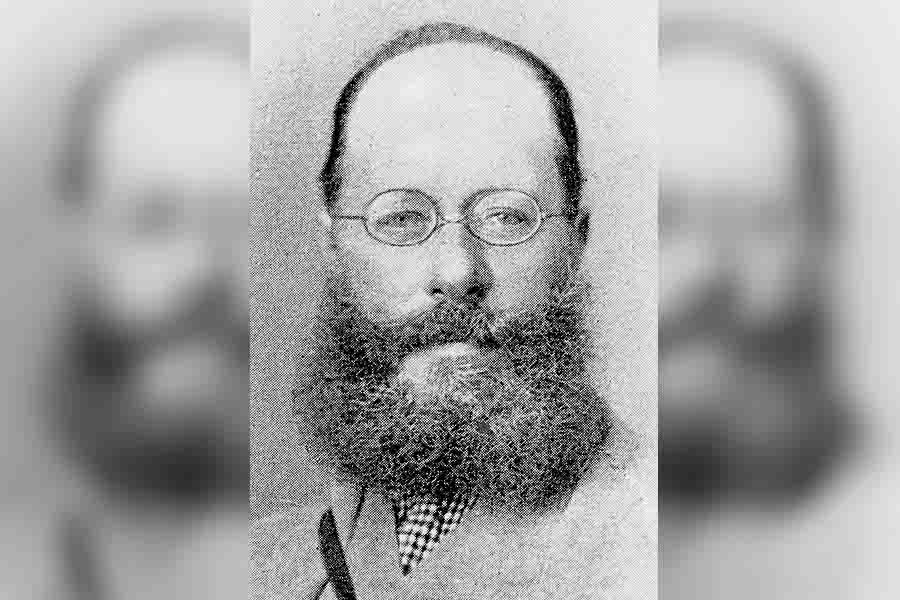

Lear was not an aristocrat and lived on the largesse of patrons Wikimedia Commons

Would you call Lear a man of Empire?

No, if by ‘of’ we mean a man who represented the power and authority of the Empire, with all its unchallenged privilege. In my novel, I wished to draw a more nuanced portrait of the man. On the one hand, he was English, his patron was the Viceroy of India, he could make his way through India because the Viceroy had made all the arrangements, including travelling in hand-carried jampans and being served by khansamas and kitmurgers. On the other hand, he, by no means, belonged to the aristocratic class, was not wealthy, and lived on the largesse of patrons. In his nonsense writings, we see him often inverting the hierarchical structures that ruled Victorian society, mocking, although indirectly, the social pretensions of that world.

You have been teaching literature for over 25 years. Why fiction and not a scholarly book instead?

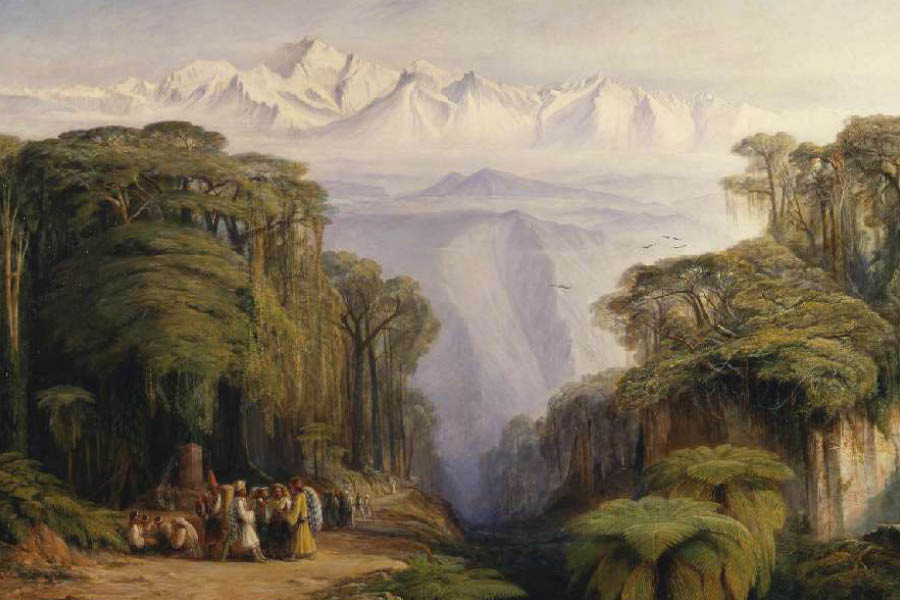

Five years before the novel was published, I had presented a paper in which I explored Lear’s difficulty in getting the “middle ground” while sketching the Kanchenjunga. I explained those passages as mirroring a kind of “colonial conundrum”, which probably stemmed from Lear’s inability to maintain the aesthetic precepts around ‘perspective’ mandated in classical Western art.

I feel that Lear’s hesitations were triggered more by anxious thoughts about what the Viceroy had commissioned — a large oil painting on canvas. Would he be able to work with oil if he didn’t get the right perspective for representing the grandeur of the majestic Kanchenjunga? Moreover, after I began to re-examine, more closely, the ellipses, the gaps and the cancelled-out passages that I saw in the Journals, I realised that under the story of his travels lay another subterranean world that he was also traversing. As if he had also embarked on an inner journey marked by his own sense of encountering the unfamiliar and dealing with the unsayable.

The novel that I then decided to write would, therefore, not be a conventional, linear travel narrative, but it would excavate that terrain of the unconscious, the unanticipated, even the uncanny. Fiction would allow me the freedom to invent the spaces found in the traces, in those gaps — and to tell those stories from his life that Lear himself could not or chose not to tell. I have to admit that my own intellectual training, in Freud and theories of psychoanalysis, and teaching about the 19th century and modernist fiction also influenced the choice of narrative form and style.

The beginning of the book is as startling as it is compelling. Why did you start with the “falling incident” in the artist’s life?

I must say that the “falling incident” is my invention. In the Journals, Lear mentions several times when he had fallen off his sketching stool or when the stool on which he sat to sketch broke and had to be fixed. To me the events in the opening chapter, leading up to him losing his balance, anticipate the most compelling dramatic elements of the story, setting up the most appropriate tone for the rest of the novel. In fact, the build-up to that dramatic event gives the reader a fuller sense of Lear as an extraordinary individual, a man driven by the obsession to take immense risks despite his own physical frailties.

Breaking through conventional symmetries of seeing, feeling and imagining

A depiction of Lear’s nonsense verse Wikimedia Commons

Which literary influences guided your narrative choice?

Most historical fiction set in the 19th century is based on thick detailing. For me, Virginia Woolf’s use of what is technically called “free indirect discourse” — where the narrative moves from the exterior to the interior, capturing the slippages between different points of view — seemed to be the most effective method for navigating through the details of Lear’s dual journey. I thought the method also paralleled, in some sense, Lear’s own style that he employed in writing nonsense verse, where he often broke through conventional symmetries of seeing, feeling and imagining.

The most important relationship I explored in detail was with Lear’s Albanian man servant Giorgi Kokalis

Famous literary, artistic and historical figures walk in and out of the pages of your book, perhaps much as they did in Lear’s life. What were the challenges and charms of humanising them, so to speak?

My sense of these historical figures came from my own research into the 19th century. Lear’s biographies provided a lot of rich material. The task of humanising them emerged as I began to scrutinise Lear’s personal correspondence (for example, his letters to his close friend Chichester Fortescue), the letters that his friends and acquaintances wrote to him, and his personal notebooks, and realised that his relationships with these figures were indeed significant. They shaped how he saw himself and the ways others perceived him, his ideas about art, travel, and also his social aspirations. In some cases, I have dramatised scenes in the novel in which their presence highlights some compelling detail about the British Empire.

In the writing of the novel, the most important relationship I explored in detail was with his Albanian man servant Giorgi Kokalis, who is by no means a known historical figure, but who figures very prominently in the Journals. Working out their relationship as they travelled and observed each other became a thread that allowed me to explore 19th century issues relating to class and dependence.

Your decades-long professional and personal engagement with both history and literature is reflected beautifully in the book. What about art?

Most of it came from viewing Lear’s art very closely, examining Vidya Dehejia’s book, Impossible Picturesqueness, which studies Lear’s Indian drawings and watercolours, exploring studies of 19th century Impressionism and English pre-Raphaelite painters, revisiting the works of J.M.W. Turner and Holman Hunt, and also by reading Lear’s books on travel. My aim was to weave ideas from all of these sources and make them relevant to the fiction without sounding too academic.

Lear moved up the social ladder and made unusual friendships

Lear’s childhood memories have been woven poignantly throughout the book. Poignant because they are memories of poverty, separation from family, and rootlessness — “no real home where you could smell the smell of Sunday stew…” How much of this was in the Journals?

Although there are scattered references to his friends and to places he visited prior to his trip to India in the Journals, most of the details about his childhood and about his attempts to establish adult relationships that I dramatise in the novel came from biographies authored by Peter Levi, Jenny Uglow, Sara Lodge and Vivien Noakes. There is also a large body of published articles that reference incidents in his life, including his childhood, his friendships, relationships with wealthy patrons in aristocratic circles, and also about his unsuccessful attempts to have fulfilling adult relationships. I was struck by the fact that although Lear suffered abandonment as a child (his father started out as a stockbroker who went into debt, which in turn led to him abandoning the family), he was able to move up the social ladder. Never wealthy, he did make unusual friendships — in fact, he met Thomas Baring, who commissioned the painting of the Kanchenjunga in Rome, striking a friendship that lasted many years. However, many of the sensory details that connect Lear to his past and that intrude into the present are my own invention, chosen deliberately to highlight Lear’s inner journey.

Food is important to Lear and in the book. Boiled mutton, tongue, cabbage soup. Why was it important to weave in food?

Lear loved food, an aspect of his personality that has been highlighted frequently in his biographies. Also, like the visual world and the world of sound, food served as a sensory medium. It also marked the boundaries of taste — the new and the old, the familiar and the different. Many of Lear’s nonsense poems feature food, from the “Owl and the Pussycat”, where the two “dined on mince and slices of quince” to the “Old Man of Calcutta”, who choked while stuffing himself with a muffin.

Thanks to Abol Tabol, we, in this part of India, love nonsense verse. Tell us a little bit about Lear’s talent and legacy as a nonsense poet.

The element of nonsense that I have attempted to trace in this journey comes mainly from Lear’s perceptions of a new world that fascinated, perplexed and occasionally repelled him, of the dizzying sound of new languages that filled the world he traversed.

Understanding the ‘new world’ through the Kanchenjunga

Lear’s painting of the Kanchenjunga TT archives

How much do the Journals speak of his difficulties in painting the Kanchenjunga and the Himalayas?

The significance of the middle ground in Western art rests on the idea that the focal point rests in it, providing balance and proportion to the painting. The question of capturing the middle ground occurs in the Journals only when Lear faces the mountain range while waiting to begin drawing. But I use that moment recursively as a kind of thematic link that mirrors Lear’s attempts to understand the complexity of the new world that he encounters not only while drawing but also on other registers — the sensory, the social and the political. It also seems relevant to Lear’s encounter with his past and in his attempts to get a sense of who he may really be in relation to that past.

Lear’s longing for home, family and romantic relationships run like an emotional undercurrent throughout the book. His unarticulated wish of “more than friendship” with a male friend is a powerful and touching part of your book. Can you tell us about the challenges of writing this without actually articulating it, given the 19th century context?

To be honest, these were the toughest elements in the novel that took time to develop. There are still raging debates in scholarly circles about whether Lear was a closeted homosexual. My intention was not to settle the debate but to dramatise how Lear was caught between his desire to maintain the norms of respectability that marriage authorised for most Victorians and his internal, hidden longing for a man who remained ever-elusive.

Lear is drawn to Augusta (Gussie), Lord Westbury’s daughter, but remains conscious of the difference in age and social class. Franklin Lushington, on the other hand, was an eminent man of social standing (he was the chief juror in the Ionian islands), his constant and sole intellectual companion in Corfu when he had very few other friends. Lear shared an interest in Greek language and culture with the juror. Lear’s longing for Lushington is caught, and often vacillates, between that fragile boundary that separates companionship, friendship and sexual attraction, a thematic pattern that I weave into the novel.

Most of what I represent in the novel is filtered through my experience of teaching about the Himalayas

For 10 years, Roy came to Kalimpong every winter Anindyo Roy

As residents of this part of the world, our readers feel a deep connection with the mountainscapes that your book talks of. A deep affection for the mountains of this part of India and an understanding of the people who inhabit those difficult terrains comes through in your writing. Can you tell us more about this?

As a professor of literature at Colby College, I set up and taught a four-week immersive learning class on the Himalayas way back in 2007. Although I have now retired from teaching at Colby, that programme still thrives under the leadership of another member of the English faculty at Colby. For 10 years, with a few breaks in between, that class brought me to Kalimpong every winter, which in turn nurtured my interest in not just mountainscapes but also in the people who inhabit that region, their traditions and their struggles. Most of what I represent in the novel is filtered through that experience of teaching about the Himalayas while inhabiting that world, including feeling the power of the sensory details, the flora, the elusive mist-filled world of change and impermanence, and sharing them with my students. The way I portray Lear during his walks — his sense of wonder at the changing landscape, at the flora, the sound of a bird call — comes from that experience. It just struck the right chord, given my familiarity with Lear’s own writings about travelling through the mountains of Albania.