Soon after arriving in New York City from India on March 18, 1959, Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife Coretta spent an evening at the home of musician and civil rights supporter Harry Belafonte. They later watched the movie The Diary of Anne Frank and met some of Belafonte’s friends. King first reached out to Belafonte because “he needed to reach out to a much broad constituency than he had been serving”. They had first met in the mid-1950s at the basement of Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York for four hours instead of the earlier agreed upon 20 minutes. Belafonte helped promote the Youth March for Integrated Schools.

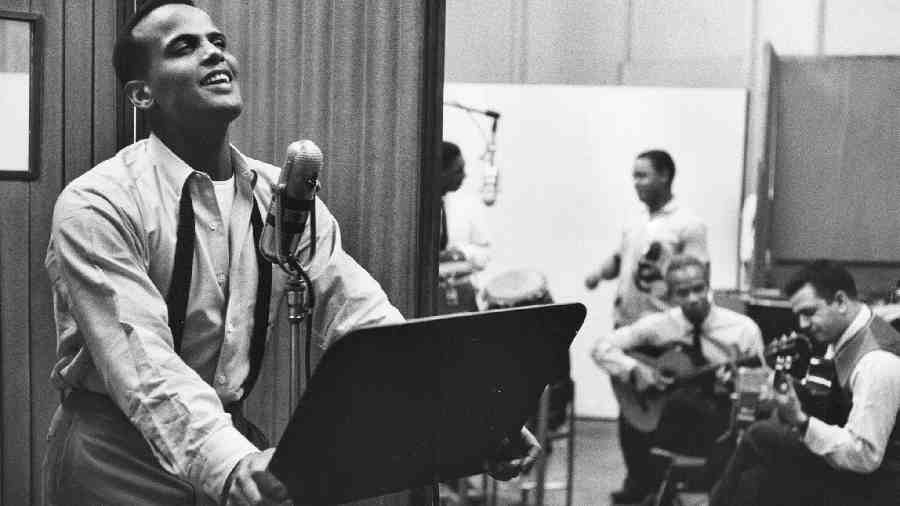

By then, Belafonte was already one of the most sought-after singers. He was the first solo singer to have a million-selling album (Calypso from 1956) and the first African-American to win an Emmy (for Tonight With Belafonte in 1959).

A plea for freedom

Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) is one of the songs we associate with the man. A distant rumbling greets listeners as if something dark is on the way. Written sometime around the turn of the Twentieth century, the call-and-response work song was a spontaneous answer to dockworkers cramming bunches of bananas onto ships.By 1890, the sugar trade in Jamaica had suffered a setback and bananas had become the country’s primary export. “Come Mr Tally Man, tally me banana,” Belafonte sings. “Daylight come and me wan’ go home,” the chorus chants. It was a plea for freedom.

Helping Belafonte deliver the song was the late songwriter Irving Burgie (he performed under the name Lord Burgess), who wrote eight of the 11 songs on Belafonte’s 1956 album Calypso.

“None of us had any idea, when we recorded it, that it would be spun off as a single,” Belafonte wrote in his 2011 autobiography My Song. The singer agreed-disagreed with RCA over the album cover. The first mockup featured him with “a big bunch of bananas superimposed on my head. I looked like Carmen Miranda in drag, only in bare feet, with a big toothy grin, as if I were saying, ‘Come to dee islands!’”

He was Mr Entertainment with a cause. He had as hero the legendary singer-actor-activist Paul Robeson. Like many other Black artistes of the generation, he looked up to him for his stirring rendition of Ol Man River as much as for his active participation to help protect the rights of exploited workers, particularly Blacks in the South.

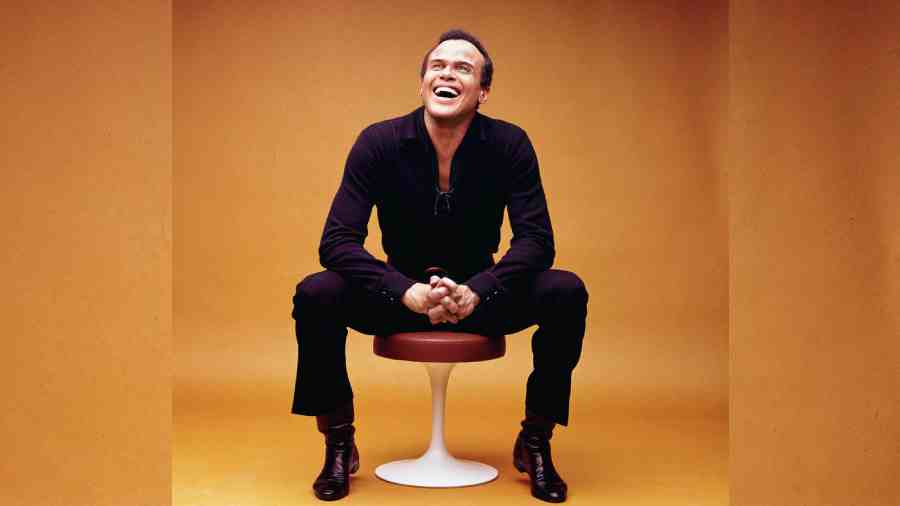

Belafonte was among the most desirable men in the US in the 1950s and 60s. He was the first Black matinee idol of the screen, the first artiste in the history of the recording industry to have a platinum album, and a success on screen as much as in the studio. At the same time, his passion for social progress was clearly evident. He was, in one way or the other, involved in every major civil rights event of the turbulent 1960s and beyond. He was Dr King Jr.’s confidant; he endorsed John F. Kennedy for president while helping him secure African-American voters; he helped orchestrate the 1963 March on Washington; he was behind the 1985 We Are the World fundraiser for African famine relief; and he helped organise Nelson Mandela’s first visit to the United States.

School, Navy and entertainment biz

Belafonte (Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.) was born in 1927, the same year that Marcus Garvey, who preached racial solidarity, was deported to Jamaica from the United States. His mother was from Jamaica and his father from Martinique. Belafonte was born in New York and spent most of his early years there. When riots erupted in Harlem in 1935, his mother took him to Jamaica where he lived for a few years. Like his contemporary and friend, Sidney Poitier, the time spent in the West Indies helped shape his view of the world. Like Poitier once said: “I firmly believe that we both had the opportunity to arrive at the formation of a sense of ourselves without having it f***ed with by racism as it existed in the United States.”

When he returned to Harlem, he found himself in a largely Italian neighbourhood. School was not his happy place. As a child he suffered from dyslexia and left high school to join the US Navy. He cleaned the decks of ships in port but it also turned out to be an educational phase. This was when he met college graduates and one of them handed him Colour and Democracy by W.E.B. Du Bois. It inspired him to read more. Stationed near Newport News, Virginia, in 1944 he met his first wife Marguerite Byrd and their “courtship was one long argument over racial issues,” she later said.

Soon after leaving the Navy, he saw a play at the American Negro Theatre (A.N.T.) in Harlem, giving him a glimpse of what was in store for him. He joined the A.N.T. where he went from working backstage to ruling the entertainment space, just like his friend Sidney Poitier.

The break that he was looking for came when he appeared on amateur night at the Royal Roost jazz tavern. He had done some singing but it wasn’t something he had seriously thought about. At first it was all jazz and then came pop songs like Lean on Me and Pennies From Heaven. It wasn’t the Belafonte we know. In 1950, he and a couple of friends opened a hamburger place called the Sage. Though it lasted only eight months, beyond work hours he rehearsed as a folk singer.

The Telegraph's favourite Belafonte songs

Harry Belafonte in 1970

Matilda

The tragi-comedy saga of a jilted Jamaican lover that attracts the singing participation of everyone in the room in which the song plays.

Danny Boy

Harry Belafonte retains the melodic purity and appeal of the original spirit of the composition. Though the song has the feel of a traditional song, the lyrics were penned only in 1910 by an English lawyer called Frederic Weatherly, set to the Irish melody of Londonderry Air.

Jamaica Farewell

A haunting West Indian song that captures the carefree life of the Caribbean.

Day-O

It is based on the traditional work songs of the people who worked the banana boats in the harbours of Trinidad.

The Marching Saints

“In American folklore we find a great deal of the European influence of music. Often I wonder what would happen if songs truly indigenous to America had gotten their start somewhere else,” Belafonte said while introducing the song at Carnegie Hall.

Sylvie

Based on a southern chain-gang song, this was on one of Belafonte’s early records. It’s the song of a prisoner longing for his Sylvie.

Mama Look a Boo-Boo

First heard by Belafonte while filming Island In The Sun, Boo Boo was a big hit.

Jump In The Line

A lively song that makes listeners “jump in the line” and join the celebration.

Island In The Sun

Belafonte always wanted people to get along, live in harmony. It’s a song with an optimistic message.

Coconut Woman

The story of a woman who sells coconut on the beach and how different people look at her.

Man Smart, Woman Smarter

Packed with delicious digs and loving barbs, the lyrics are humorous.

There’s A Hole In The Bucket

Harry Belafonte recorded it with Odetta in 1960. It remains a favourite among children and anyone with a sense of humour.

Martin Luther King Jr., Harry Belafonte, Asa Philip Randolph and Sidney Poitier in 1960

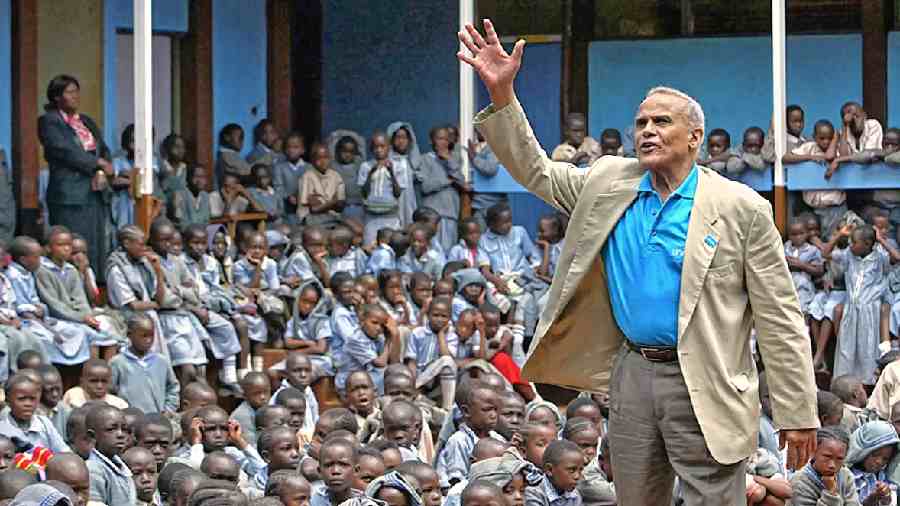

In his capacity as UNICEF goodwill ambassador, Harry Belafonte visited Kenya in 2004

What he did was add a new dimension to folk singing by punctuating it with West Indian folk songs. The legendary Village Vanguard awaited him and then the venue, Blue Angel, and then a contract as a recording artiste at RCA.

The charismatic singer soon was known for calypsos like Matilda and Lead Man Holler as much as for ballads like Scarlet Ribbons. By 1959 he was the most highly paid Black performer in history.

Star of the screen

At the same time, his movie dreams were also maturing. Once the film industry’s Production Code lifted its ban on showing interracial sexual relationships in movies, Belafonte played the love interest of Joan Fontaine in Island in the Sun (1957). Yes, it’s one on which he sang the dreamy title song. Now considered a classic, the film came at a tough time for Belafonte. While filming he somewhat managed to keep two events away from the public eye — his divorce from Marguerite and his subsequent marriage to Julie Robinson, who was earlier dating Marlon Brando. News of the second marriage leaked around the time the film released.

A couple of years later he was seen in Robert Wise’s Odds Against Tomorrow in which he brilliantly played Johnny Ingram, the club singer with a mountain of debts who is forced into helping rob a bank. That same year he delivered one of the best roles of his career in the sci-fi fantasy The World, The Flesh and The Devil. He played mining engineer Burton, trapped miles below the surface of the earth. He escapes a cave-in resulting from an atomic catastrophe; when he appears, Burton is apparently the only human left alive. Soon we find that there is also one White woman and one White man.

Another outstanding performance was opposite John Travolta in White Man’s Burden from American-Japanese film-maker Desmond Nakano. Another fine performance came in Robert Altman’s 1996 drama Kansas City.

His everlasting legacy

He spent most of the 1960s engaged with the civil rights movement, helping Dr King. Besides providing money to bail Dr King and civil rights activists out of jail, he took part in the March on Washington in 1963. He even maintained an insurance policy on Dr King’s life, with the King family as the beneficiary. When Dr King was assassinated in 1968, the first thing on his mind was taking care of the family.

His power to draw audiences is well-documented. In 1968, he became the first Black fill-in host for Johnny Carson on NBC’s The Tonight Show and he used the platform to entertain as well as talk about civil rights, the Vietnam War and starvation in Appalachia. That very year he and British singer Petula Clark performed a duet of the antiwar song Paths of Glory on an NBC special, even though there was an objection from an advertising manager for an automaker.

Decades later, he was awarded the title “goodwill ambassador” for UNICEF. It gave him an opportunity to unite artistes and intellectuals in Africa to focus on issues like hunger, polio and malaria.

Belafonte’s 1962 album The Midnight Special was something a young Bob Dylan looked up to. Dylan, in his memoir Chronicles: Volume One, wrote: “He could play to a packed house at Carnegie Hall one night and then the next day he might appear at a garment centre union rally. To Harry, it didn’t make any difference. People were people. He had ideals and made you feel you’re part of the human race. There never was a performer who crossed so many lines as Harry.”

Belafonte fought poverty, racial disparity and went against all odds to make music that was unique. Like he once told The Guardian: “I’m a driven man. Driven by ego, driven by conscience, always looking for another song.”