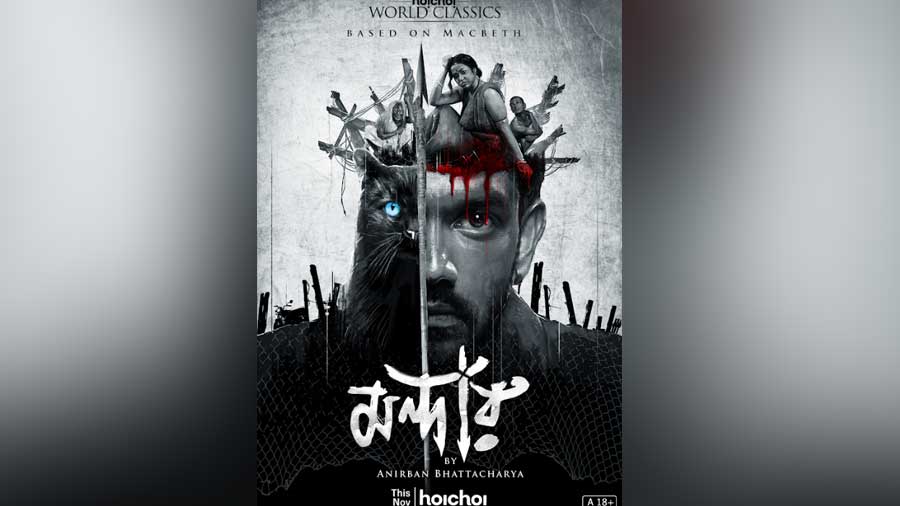

Mandaar, the maiden venture in Hoichoi’s new property, World Classics, is not only by far the best series in the fledgling Bengali OTT space till date, it is by miles the finest cinematic work emanating from a largely moribund industry in a while. With a technical crew – cinematographer Soumik Haldar, editor Sanglap Bhowmik, production designer Subrata Barik, sound designers Adeep Singh Manki and Anindit Roy, and composer Subhadeep Guha – at the top its game, debutant film-maker Anirban Bhattacharya’s series is nothing like what you have seen in the Bengali landscape.

A hypnotic, visceral and hugely entertaining adaptation of Macbeth, Mandaar sets a new bar for film-makers to aspire to. I caught up with Anirban Bhattacharya

Tell us something about the gestation of the series...

Anirban Bhattacharya: I have lived with the thought of adapting Macbeth for a long time. Not because I found something of political or social relevance in it… rather it was the timeless element of Shakespeare’s plays that attracted me. And I wanted to do it for theatre. I wanted to call it ‘Mogoje Macbeth’, with a regular office-goer, say, someone working in an IT hub, a medical representative, as the protagonist. What if someone like that gets obsessed with the power play of Macbeth?

This idea has been with me since 2012. It’s only after I entered cinema and Hoichoi came into being and OTT became an avenue to reckon with, did this begin to take shape. Moni-da and Shrikant-da (Mahendra Soni and Shrikant Mohta of SVF) asked me if I had any stories in mind

Mandaar is a by-product of the pandemic. We were all house-bound and our executive producer Abhishek-da brought it up sometime in May 2020. Then Pratik, my co-writer, and I got down to it, with inputs from a friend of ours, Rudrarup Mukhopadhyay, a student of English literature. Before delving into the screenplay, we created a short structure from Macbeth, just delineating the basic plot points.

Debashish Mondal as Mandaar Hoichoi and SVF Entertainment

Big fish eating small fish

Setting it against the backdrop of a fisheries village in East Midnapore. How did that come about?

We had a few elements in mind when it came to the geographical backdrop. We were talking of contemporary society, not kings and dukes. But there’s a grandness to Shakespeare’s plays… the palaces or, say, the barren landscape through which Macbeth and Banquo ride their horses. How could we replicate those elements in modern times? We realised that we needed to look at Nature in all its desolate grandness. That led us to think of forests, seas, mountains as possible backdrops. We brainstormed about this… how about the sea… with the aspect of the proverbial ‘big fish eating small fish’. An image came to my mind… a fish caught at the end of a spear. That’s how we started ideating.

With the sea also came the idea of setting the narrative in a fishery belt -- not that our story had anything to do with fisheries, though our Duncan (Dablu Bhai) owns one and Mandaar and Bonka are basically fishermen who double up as musclemen and hitmen. We needed to check whether we could include aspects of criminal activities if we were setting it in a fishery. Pratik did some research on that and we were satisfied with what we discovered. We were not making a crime thriller, a cat-and-mouse game… the elements of crime were tangential to the basic story that dealt with human emotions and power play. So, that’s how it all developed… elemental Nature, sea, fish, fishery belt, boats, the grey muddy seas which decided the colour scheme for the film.

Anirban Bhattacharya as Mukaddar Mukherjee in ‘Mandaar’ Hoichoi and SVF Entertainment

A hungry man is a demon!

And the three witches… the mother, son and the cat here. That’s a very interesting take on the witches. Take us through the ideation for this.

(Laughs) To convey what I had in mind as a director for the witches – in this case Majnu Budi, Pedo and Bedal (the cat) – required a certain level of skill or erudition. I have no hesitation in admitting that maybe I haven’t been able to achieve it as I had visualised. As creators we were caught in two minds. Consider the sound design… what Majnu Budi or Pedo say echoes, resonates, in a certain way… that has a supernatural element to it. But eventually we discover that they are human after all – they can be killed and they can kill. My idea was that they were what we would call ‘Dalit’… belonging to the depressed caste aboriginal strata. If you look at it through an economic prism – you have Dablu Bhai, Mandaar and the witch. Mandaar kills Dablu Bhai, the witch kills Mandaar… we have done away with Birnam Wood and instead of Birnam Wood coming to Dunsinane, it is the witch, the subaltern, that ‘moves’ to kill Mandaar.

I wanted a cinematic/symbolic representation of that and I am not sure we were entirely successful in the attempt. I think the socio-political aspect that I wanted to convey hasn’t come across as well as I would have liked it to. It needed a greater control over nuances of the screenplay which I hope will come with experience. I wanted Majnu Budi and Pedo as representatives of outcasts, people who have been marginalised … who comment on the community they have been discarded from… Hunger! Hunger! Blame it all on Hunger! A hungry man is a demon! That was the essence of my visualisation of the witches – what we call civilised society is afraid of the outcast, their demeanour is frightening, they have been rendered animal-like, but it’s the so-called civilised society that’s actually barbaric.

Sohini Sarkar as Laili in ‘Mandaar’ Hoichoi and SVF Entertainment

Lady Macbeth time and again questions his manhood

Talking about Mandaar’s sexual dysfunction and the interplay of sex and power in your adaptation, the impotence (weakness) is alluded to in the original but here it comes to the forefront.

I have always believed that sexual desire is an integral part of our lives, be it a metropolitan city or the back of beyond. If you consider Manik Bandopadhyay’s Putul Nacher Itikatha and that seminal exchange between Kusum and Sashi, where Kusum tells the doctor how her body feels all uneasy when she is close to him, to which Sashi responds, ‘Shorir, shorir, tomar mon nayi, Kusum.’ (The body, the body, don’t you have a heart, Kusum?). A lot of our classic literature deals with sexual mores in rural areas which appear more liberated than what we see in our cities. I look at it as primitive sexuality that is beyond a social structure, commitment as we define it in our ‘modern’ cities.

Since there’s a taboo around the subject of sex in our society, since discussions around it are largely suppressed, there’s a lot that happens at a subterranean/ hidden level. Those who have been able to accept it as a social act, have been able to come to terms with it, integrate it as part of their everyday routine, have a different language when it comes to sex. Let’s consider someone who accesses pornographic material all day – be it on social media, on the Internet – someone who is addicted to that will probably resist loudest when that finds a way into the mainstream. It is as if the most private of my secrets, my desires are out there for the world to see. And that becomes unacceptable.

The film begins with Mandaar masturbating. Now, the act of masturbation is something every man – impotent or otherwise – is well aware of. But, when it comes to showing something as private as that on the screen, given our sexual exposure, the kind of conversations we have had around sex, that probably makes it difficult for our audiences to accept.

When it comes to Mandaar specifically, we wanted to bring out the contrast between his well-sculpted physique, yet his inability to have an erection. In Macbeth too, Lady Macbeth time and again questions his manhood – though it is done in an asexual context. We have contemporised it to include sexuality because that leads to certain interesting psychological possibilities. Mandaar does not have natural sexual prowess – he needs medical supplements to overcome his sexual inadequacies and that subsequently emboldens him to take the steps to eliminate his rivals. He is ‘hiring’ his powers from external sources. That subtext exists in Macbeth becoming the king too. The subversion lies in the fact that Macbeth wasn’t king material… Duncan was a good king, Macbeth was not – hence he cannot hold on to his kingship. I see parallels to this in Rabindranath Tagore’s play, Raja, too.

A still from ‘Mandaar’ Hoichoi and SVF Entertainment

We are unfortunately slaves to what we call ‘logical’ viewing

Mandaar is one of the most innovative visual and aural designs I have seen in Indian cinema. From workers dressed in faux Barcelona shirts, Dablu Bhai’s son wearing a Che Guevara tee while beating up a worker, the sound of a child’s laughter as Laayli’s ringtone, the fluid camerawork juxtaposing top-angle shots with static shots that seem like we are in a play, the expert use of music (that haunting flute refrain, say, in the dream sequence on the beach in the second episode)....

All of these were part of detailed pre-production including multiple recces to the location. Our first visit happened after we had written the first draft. I was never in doubt that the locales and the lives we would portray through the film would be done through an intellectual prism. I wanted to convey these lives objectively. I was clear that we were not trying to make ‘realistic’ content. You could say we were trying to create something theatrical, dramatic; we were trying to transform a play into cinematic visual from a given circumstantial zone – a text that does not adhere to the tropes of realism to begin with. Our cinematic language needed an element that at the outset needed to convey that to the audience subconsciously.

We are unfortunately slaves to what we call ‘logical’ viewing – we look for logic in everything that we see unfolding before us on screen. The legendary Utpal Dutt used to say, ‘There’s a logic to performance; a character has none.’ Human beings are not logical. If we were a logical species, our history would have been very different. When we represent this through art, though, there are certain logical balances that we need to be aware of.

When we talk of Mandaar’s cinematography, its core mise en scene originated primarily from this need to keep the audience at a distance from this bondage to logic. We needed to create a phantasmal look, so that we could make the viewer part of the subversion. This is what I discussed with Soumik-da (Soumik Haldar) and the rest of it owes itself to his pure genius. I was just a student. We had detailed shot divisions done so that at the time of shooting we were clear of what a particular shot would achieve.

For the music, I had narrated the concept to Subhadeep Guha. He has worked on Macbeth numerous times on stage. The natural sounds we had included... the sea, the cawing of crows. Then he created what we call a ‘scratch’ version of the music. Having worked with him in theatre for years now – he has composed for each one of my theatre productions – we operate on similar wavelengths. And that scratch recording gelled with what I had in mind. What was great about the music was that despite its apparent raw quality, there were times when it sounded urbanised – the use of instruments, a certain attitude to the music – that underlined the objectivity I was looking for.

Dablu Bhai owns a fishery while Mandaar and Bonka are fishermen who double up as musclemen and hitmen Hoichoi and SVF Entertainment

What you get is not what you see, with Mukaddar

Coming to the character you play – Mukaddar Mukherjee. That’s an addition at your end. What was it that prompted you to have him talk in English? The music he plays on his mobile is as alien to the landscape of Mandaar as to jolt you with its innovativeness. His penchant for food (you have so many scenes of him eating). The almost feminine way he speaks. Give us an understanding of his character as you developed it.

Mukaddar owes itself to a conversation I had with Pratik. I called him one night to say that here was a landscape teeming with crime, don’t we need someone to represent the police? The first draft did not have Mukaddar. It was a decision purely driven by narrative requirement. It’s interesting that viewers have found myriad aspects to the character.

That he often breaks into English was meant to highlight a foreign element – but to make the character interesting we decided that his diction/pronunciation wouldn’t be ‘propah’. The way he articulates ‘whose cycle is this’ isn’t really how someone conversant with the language would. There’s something about the way he speaks in English that conveys there’s something distorted about him.

The glasses he wears, his sideburns – all of these were part of making the character sleazy. What you get is not what you see. Food – meat, liquor – is an integral part of not only Mukaddar’s character but also in the overall scheme of the narrative right from the outset. Mandaar himself is shown gobbling meat, Dablu Bhai eats chhana.

Were you ever apprehensive about the dialect, that it could be difficult for a general audience to follow? Like the landscape, the film’s language is also a character. Tell us about your choice of this dialect and working around that.

The dialect grew out of the location. A city-bred dialect wouldn’t have worked for the characters. I am from West Midnapore and am aware of only a few intonations of the East Midnapore dialect. The dialects of Purba and Paschim Midnapore are diametrically different. I started working with our local coordinators Jyotirmoy, Rajkumar, Sujit-da on this. My assistant Ujaan sat down with people in the region to transform the whole dialogue bit by bit to the local dialect. But we realised that if we kept it to the authentic dialect of the region, audiences would understand nothing – we could well be talking Chinese. We had to be mindful that as an audience we are not quite exposed to rural dialects. That’s when we decided to trim the language to make it accessible while retaining the nuances, the hard music of the dialect. I did not think about it as a risk so much as something that complements the narrative. And I think viewers have seen the merits of our decision.

Debashish Mondal, Anirban Bhattacharya and Sohini Sarkar SVF Entertainment

These are all fantastic actors I have worked with

A note on the selection of actors. These are largely hitherto unseen faces, drawn from theatre. They look like they emerge from the landscape, belong there. Even Sohini (Sarkar) is far removed from the actor we have known so far.

The decision to cast actors primarily from theatre was not premeditated in any way. I needed a certain kind of ‘face’ with a certain level of acting capability which I serendipitously found in theatre. The casting was entirely organic in nature. These are all fantastic actors I have worked with. Actors whose performances on stage I have enjoyed watching. Yes, people have responded to Sohini’s performance with a lot of praise. She put in a lot of hard work to convey the look and essence of the character.

Theatre has shaped my life, my personality

How has your background in theatre shaped your vision for the series?

Whatever I do – be it acting, writing, composing, singing – all of these are informed by my training in theatre. I owe all my learnings to theatre. Coming to cinema, I have only worked in the medium but it has not trained me for anything – that credit belongs entirely to my tryst with theatre. Cinema has given me a certain experience over the seven years I have been a part of it. It has given me some technical inputs. But it is theatre that has moulded me, made me the artiste I am, introduced me to everything I have learned about my craft, given me the cultural exposure so necessary for a creative endeavour. So much so that even when I speak to someone, or watch some other content, I can feel the presence of my theatre background. Theatre has shaped my life, my personality.

Whatever you create exists within the wheels of the Modern Times machine

What next? Where does Anirban go from here? You have set the bar impossibly high both for yourself and for cinema in Bengal!

(Laughs) I really don’t know. I am aware of the inherent charm of your first initiative. Its acceptance is as influential as its rejection. But I am also aware, we no longer have cinema – we have content. We have concepts now, not stories. It’s no longer work, but projects. We have arrived in a corporatised world of making and viewing content. I look at myself as a machine because in the capitalist structure of art-making, whatever you create exists within the wheels of the Modern Times machine. Yes, you can always keep the machine lubricated and in good condition. But there’s no getting away from the fact that one is now entering a factory. There will be a perception about my work going forward, there will be a trend that viewers and makers will expect from me. One’s first enterprise gives one the freedom to try out something new, be innovative. After that, you always run the risk of being boxed-in by both makers and viewers.

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a publisher, editor and critic. He has worked with leading Indian authors and books commissioned by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI award for best writing on cinema. An avid film buff, he loves poetry and music.