A film that can be described as a parable for racism and colonialism, The Survival of Kindness is quiet, melancholic and meditative in all its moments. Especially in its violence. Its maker Rolf de Heer, a doyen of Australian arthouse cinema known for his radical works, was in Kolkata for the 29th Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF), where his award-winning film was screened.

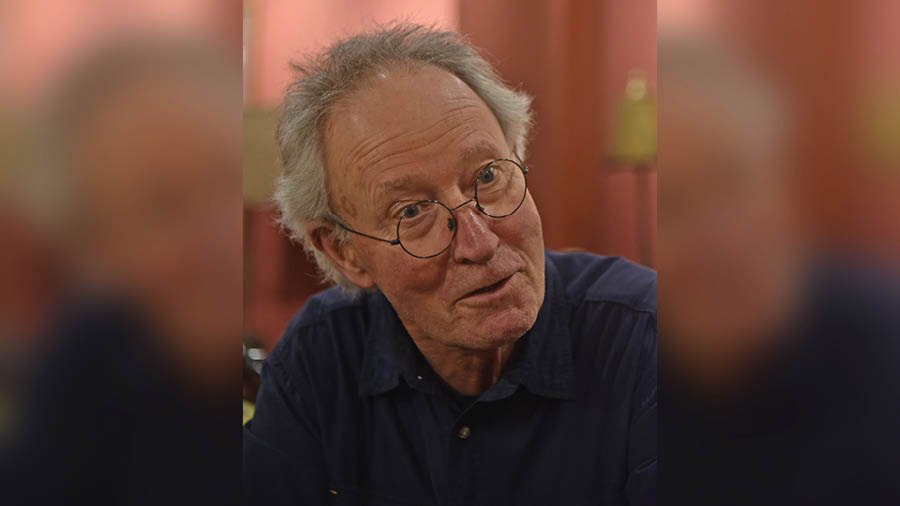

Rolf de Heer on stage at Nandan after the screening of his film ‘The Survival of Kindness’

The Survival of Kindness is set in a post-apocalyptic landscape, after an unexplained epidemic has infected and killed white people. The survivors wear gas masks and become enslavers, torturers, tyrants and harassers to people of colour (who have not been affected by the disaster) in this lawless time. The film follows an enslaved woman, first seen abandoned in a locked cage on a trailer in a desert, in the middle of nowhere, and her journey to take back her own freedom and travel across the desolate and dangerous terrain that remains. This character, referred to only as Black Woman in the credits, is played by Mwajemi Hussein in an incredible performance.

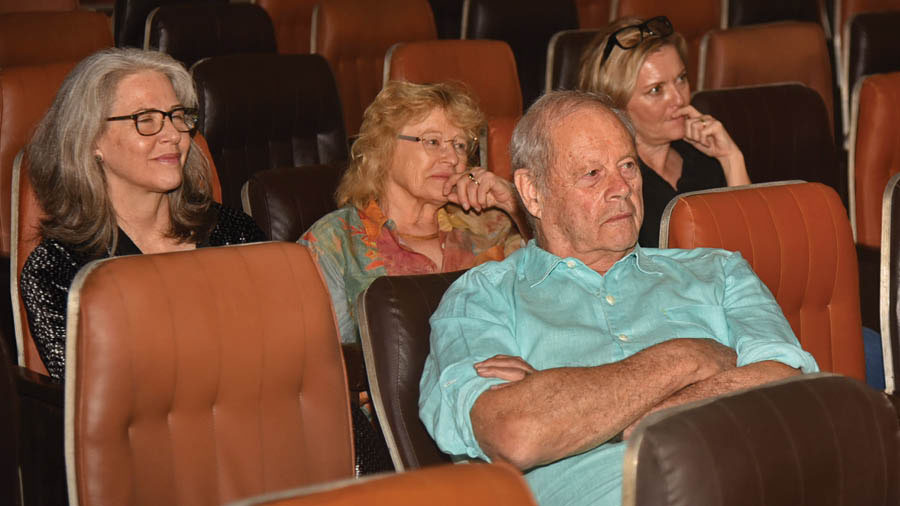

Legendary Australian filmmaker Bruce Beresford (front row) was in attendance at the screening

The film is poetic in its crests and troughs, and intense in its storytelling, even though de Heer refuses to use any dialogue. The Survival of Kindness takes the audience on an incredible journey, and it makes the film’s ending that much more haunting.

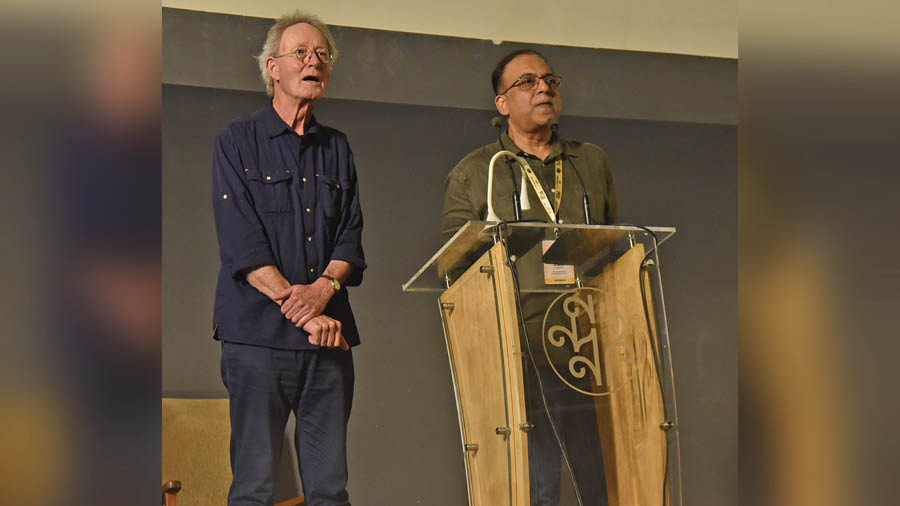

Rolf de Heer (left) with Bengali film director Arindam Sil

After the screening, Rolf de Heer shared the stage at Nandan with filmmaker Arindam Sil for an interactive session with the audience. The Dutch-Australian filmmaker spoke about his passion for filmmaking and how working in Hollywood doesn’t interest him because “I don’t think I would be very good at making that kind of film”. He also spoke about the troubled and ‘complex’ production of The Survival of Kindness, born partly from the Covid-19 lockdown situation in Australia, and the experience of shooting the film amidst the wide open landscapes of the Australian states Tasmania and South Australia. My Kolkata caught up with de Heer and chatted about his career so far, The Survival of Kindness, what cinema means to him, and much more. Edited excerpts follow.

My Kolkata: What has your experience been like at KIFF?

Rolf de Heer: I’ve been here for 24 hours, it’s been spectacular. The ceremony (the KIFF opening ceremony) last night was fantastic. Incredible, enough to make you laugh in a very positive way. Today has been very busy, and tomorrow, at 4 o’clock in the morning, I leave. It is my first time in Kolkata, and I hope to be back again.

One of the major subjects your film deals with is racism. What do you feel are the attitudes towards indigenous and minority communities in Australia?

There are many attitudes in Australia towards indigenous people — it’s very mixed, and the attitudes continue to be troubled, and troublesome.

‘You can have a man looking at a baby’s poo-ey nappy, and if it’s done well, and people laugh because of it; that can be cinema’

In The Survival of Kindness, you do not rely on dialogue. A persistent theme in your work has been the subversion of traditional storytelling techniques. What, according to you, do you think is the language of cinema?

The language of cinema is very varied. You can have a great actor deliver a line of dialogue, and that is cinema. You can have no dialogue, and it’s expansive — one person walking on a big landscape, and that’s cinema. You can have 50,000 horses and people sweep through the shot; that is cinema. You can have a man looking at a baby’s poo-ey nappy, and if it’s done well, and people laugh because of it; that can be cinema.

Throughout your career you have been very brave and taken several leaps of faith to tell the kind of stories you have told. What drives you? What is the motivation to keep challenging yourself in these scenarios?

Each film is a glorious adventure, and to be able to spend my life in glorious adventures, you don’t need motivation for that. They (films) are glorious adventures because I can make them and not have to try and get a hundred thousand people to see them all the time, you know? I can make it for what it wants to be. Some of them work, and then some of them don’t quite work, in terms of audience.

In your 1991 film Dingo, you had the chance to work with jazz legend Miles Davis. What was it like to work with him?

Look, it was so unexpectedly good that we were talking about doing another film together where he would be the lead. That film was not about music, and it was about him as an actor. He had something, you know? He had some capacity. Unfortunately, he passed away, and we never got a chance to do it. Working with Miles was really an unexpectedly good time, and his manager said part of the way through the movie, ‘What have you done? I have never seen him so cooperative, ever!’