Demi Lovato woke up legally blind in an intensive care unit after the July 2018 drug overdose that nearly killed her. It took about two months to recover enough sight to read a book, and she passed the time catching up on 10 years’ worth of sleep, playing board games or taking a single lap around the hospital floor for exercise. Blind spots made it nearly impossible to see head-on, so she peered at her phone through her peripheral vision and typed using voice notes.

“It was interesting how fast I adapted,” she said in a recent interview. “I didn’t leave myself time to really feel sad about it. I just was like, how do I fix it?”

Lovato, the 28-year-old singer, songwriter, actress and budding activist who has been in show business since she was six and a household name since her teens, is not just adaptable — she is one of the most resilient pop cultural figures of her time. She got her start on kids’ TV and made the tricky leap to adult stardom, releasing six albums (two platinum, four gold), serving as a judge on The X Factor, acting on Glee and Will & Grace and amassing 100 million Instagram followers — all while managing an eating disorder since she was a child, drug addiction that started in her teens, coming out as queer and the constant pressure of being an exceptionally famous person.

She recounts her relapse and overdose unblinkingly in the documentary Dancing With the Devil, which recently premiered at the South by Southwest Film Festival. A song with the same name, a brassy, haunting showcase for Lovato’s powerhouse voice, anchors a new album, Dancing With the Devil … The Art of Starting Over, due April 2.

Documentaries from pop stars about themselves have become a cottage industry, but most feel like sanitised marketing tools and grasp for friction, like the stress of fame or loneliness. Lovato’s film, which follows Simply Complicated in 2017, is all tension — 90-plus minutes of mostly interviews directed by Michael D. Ratner — and doesn’t gloss over the ugliest realities. She reveals excruciating details about a history of sexual assault, self-harm and family trauma, one troubling scenario colliding into another like dominoes. The film and album are part of a comeback attempt that puts a core part of the Demi Lovato proposition to the test: How honest can she really be?

Pop stardom is a high-wire act on the continuum between fantasy and reality, spectacle and authenticity, escaping and relating. There are the otherworldly untouchables who appear to hover tantalisingly out of reach (Beyonce, Lady Gaga), and the seemingly fully knowables who feel just an arm’s length away (Kelly Clarkson, Miley Cyrus). A lot depends on how much a musician reveals to her audience. And Lovato has always been a sharer.

Dancing With the Devil is filled with fresh admissions that betray previous obfuscations. Her overdose came after six years of sobriety, during which Lovato felt increasingly hemmed in by the measures her longtime managers took to help her stay on track. It caused three strokes, a heart attack and organ failure. She had pneumonia from asphyxiating on her vomit; she suffered brain damage from the strokes, and has lasting vision problems. (She can no longer drive and described the lingering effects as resembling sunspots.) The drug dealer who brought her heroin that night sexually assaulted her, then left her close to death.

Demi Lovato perched in front of her laptop for two lengthy video interviews from her airy new home in Los Angeles in February and early March barely resembled the pop star narrating her recent history in the documentary, though she spoke candidly with the same disarming charm. Unlike the long-haired, glam-squadded Lovato on film, this one served dorm-lounge pandemic realness: a close-cropped haircut, big, clear-framed eyeglasses and oversized sweats. And she frequently let out loud, un-self-conscious laughs as she debated when she’d shower next or recalled singing Christina Aguilera’s part of Lady Marmalade “way too many times” for a nine-year-old. (“I couldn’t tell you what it was about, but I could tell you all the vocal ad-libs she did.”)

Lockdown, like the recovery time following her overdose, forced Lovato to take a breath, though she spent its first seven months in a whirlwind romance that ended in a broken engagement. (More on that later.) “My spiritual healer had warned me last year and said, ‘Hey, just so you know, things are about to slow down, like, a lot,’” she said.

In early 2020, a pause wasn’t in Lovato’s plans. She had a new team led by Scooter Braun, the manager and entrepreneur who oversees the careers of Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande, and returned to performing at the Grammys and the Super Bowl. But re-entering the pop mainstream after a very public overdose on hard drugs wasn’t a guarantee.

“I saw that she was scared, like, no one’s going to take me on,” Braun said of their initial meeting in an interview. “I asked Ariana’s opinion and she said, let me go to coffee with her,” he added. “And by the time she got home, she texted me: You have to take her on, this is my friend. I want to know she’s safe.”

There would be no album or tour in 2020. But the changes Lovato has undergone — particularly since her August birthday, she said — have put her on a different course. She’s increasingly devoted herself to activism, meditation and, despite her vision difficulties, reading. “This last year provided me so much self-growth and was so beneficial to my spiritual evolution,” she said. And Braun listed the one goal he has for her moving forward: “To live a happy life.”

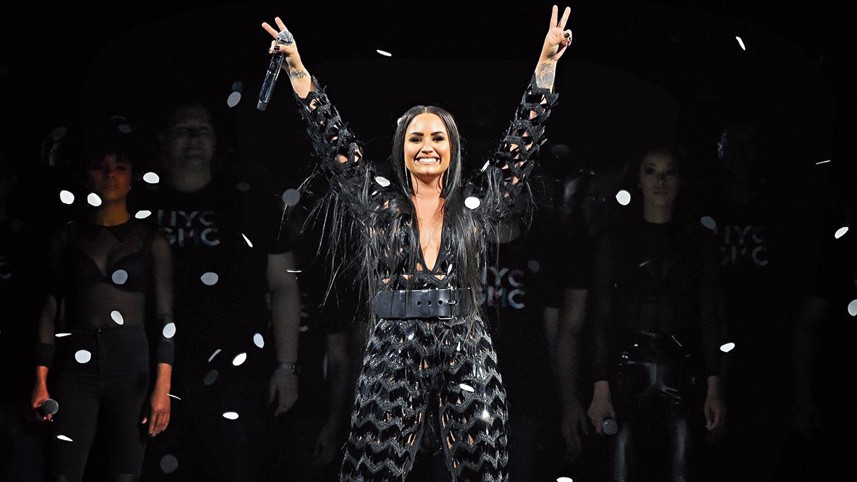

Demi Lovato performing during the Tell Me You Love Me World Tour at Barclays Centre of Brooklyn in 2018 in New York City. Picture: Getty Images

‘I embraced my independence’

Amy Winehouse was found dead of alcohol poisoning on July 23, 2011. That same date seven years later, Lovato began the night of partying that ended in the I.C.U. Amy, the 2015 documentary about the British musician, played at Lovato’s rehab facility. She couldn’t bring herself to watch it.

“I did definitely look up to her and I valued her vulnerability and transparency with her audience because it bred that connection that I felt to her,” she said. “And that’s ultimately what my fans feel with me.”

When she was a Disney star, Lovato had an edgy candour that distinguished her from the pack. A few months before she turned 16 and released her debut album, she was on tour with the squeaky-clean Jonas Brothers and answered a reporter’s questions about her musical tastes. “What fascinates me,” she said, “is metal,” naming very heavy bands. Lovato recalled worrying that she would get in trouble. “I remember feeling like I know that I’m a role model and I’m not supposed to like this dark metal music, but I do.”

At 18, she attended rehab for physical and emotional issues after being caught doing drugs and assaulting a dancer on tour, and was told that she had bipolar disorder; she went public both to explain her actions and help dispel the stigma around discussing mental health. (Lovato says she never received that diagnosis again, and now believes it was incorrect. “Turns out I have ADHD, but I’m not bipolar,” she said.)

“I could be honest with the world at 18,” she explained. “I could tell the world my dirty, dark secrets. I didn’t care. Because if I told you my secrets, you had nothing on me.”

Looking back at her days of teen stardom through the lens of an adult, Lovato has compassion. “In hindsight, I don’t blame my 17-year-old self for being so miserable,” she said. “When I’m angry, it means that I’m actually hurting,” she added. “Young women in the industry who get labelled with ‘difficult to work with’ — it’s like, hey, maybe just for a second, consider that it’s not that I’m a bad person. It’s just that nobody’s listening to me and I’m hungry, and I’m tired and overworked and doing the best I can for an unmedicated 17-year-old.”

Exposing her imperfections to the world did little to alleviate internal pressures, though. Behind the scenes, Lovato pushed herself to be the idealised version of a successful pop star as her career progressed. Her first two albums from 2008 and 2009 were filled with spunky pop-punk in the mode of Ashlee Simpson and Avril Lavigne. Her third LP, Unbroken, which included the hit ballad Skyscraper and the irresistible Give Your Heart a Break, was a creative leap, adding more R&B influences and serious subjects.

She said she avoids revisiting her subsequent two albums, Demi (2013) and Confident (2015). “I don’t know if it’s because it reminds me of the people that were in my life during those times or if it just doesn’t feel that authentic to myself,” she said. “I had really believed in myself after putting Skyscraper out, for the Grammys. I was like, I might have a shot now! And then I put out another album — nothing.”

Discouraged by the reaction, she recalibrated. “So I dove into, all right, what is the formula for a pop star that’s top of the charts?” She counted off the criteria on her right hand: “She shows her skin, she’s a lot fitter, and you know, she wears leotards onstage. So I played that role for a minute. And that didn’t fulfil me at all.”

Fired up, she continued: “It’s weird to think that I had more sense of identity as a 15, 16-year-old than I did as a 23-year-old.”

One song from that dark period in 2015 did hark back to Lovato’s earlier work, with its disco-punk chorus driven by grindy guitars. Cool for the Summer spoke the most truth, about hooking up with girls. Lovato heard its beat at the studio of the producer Max Martin and was immediately captivated: “I was like, we have to write to that. That’s so [expletive] hard.”

When Cool for the Summer became inescapable, Lovato broached the track’s subject with her stepfather. “I was like, ‘Well, I should just let you know, I like girls.’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, you have a No. 1 song out right now that’s about that, so you’re not fooling anybody.’ And I was like, ‘Good point. Maybe I should tell mom.’”

She did, but not until two years later, before she went on a date with a woman and presumed photos would end up online. “I put a lot of negative expectations on that conversation that I wish I hadn’t,” Lovato said, resting her chin on her hand embellished with a lion head tattoo. “Growing up in the South, growing up as Christian, I was scared to know how she’d react.” (Her mother’s response? “I just want you to be happy.”)

Lovato hadn’t kept her queerness a secret, but she didn’t make many public pronouncements about it until her 2017 documentary, when she said she was on a dating app for both men and women. In March, she started seeing a male actor, and the relationship progressed quickly in quarantine, resulting in a July engagement. But in September — a month after her birthday — Lovato called it off.

“I feel like I dodged a bullet because I wouldn’t have been living my truth for the rest of my life had I confined myself into that box of heteronormativity and monogamy,” she said, her voice sparking with energy. “And it took getting that close to shake me up and be like, wow, you really got to live your life for who you really are.”

Lovato’s understanding of her identity, as well as the status of her physical and mental health, has been complicated by the matrix of pop stardom. But a new generation of artistes, including Billie Eilish, is pushing back against long-held expectations. “I think it was when Billie started wearing the baggy clothes that was the first time I was like, I don’t have to be the super-sexy sexualised pop star,” Lovato said. “And it also never felt that comfortable to me. Like it’s not the most natural thing to me to go onstage in a leotard.”

That perspective shift led to a cascade of questions: “If I’m not the sexualised pop star with a big voice, then what am I?” Lovato asked herself. “I feel like ever since that awakening, I embraced my independence. I embraced the balance of both masculine and feminine parts of me. And I do feel in control more so than I’ve ever felt in my life.”

In November, Lovato hosted the People’s Choice Awards in a series of luxurious, flowing wigs because “I’m going out with a bang.” Then she chopped off most of her hair, a move that “felt like the first step in fully embracing myself,” she said. It was even shorter by the time we spoke. “I’m still on a journey to finding myself and this haircut was just one step of the process,” she added. She left the topic with a hint: “More will come about that in time.”

Demi Lovato played an aspiring singer in the television film Camp Rock, from 2008, about a summer music camp. Picture: ABC and Disney Channel

‘I am ready to feel like myself’

Lovato is from a lineage of megawatt pop singers who can flatten you with a single-belted note. The smash off her last album, Tell Me You Love Me from 2017, was Sorry Not Sorry, a delectable aural finger wag. But it’s impossible to divorce the sheer force of her lungs from the personality animating it: “You’re like, how does she sound like this?” said her friend Noah Cyrus. “She’s flawless, and flawed in all the most perfect ways, all of her raw emotion is there. And that’s what makes the most amazing artistes.”

Her new album has its share of vocal pyrotechnics, but is a far more intimate LP, focused on telling the story of the past several years. Its oldest song was recorded on Valentine’s Day in 2018; its newest, a collaboration with Ariana Grande, was added in the last few weeks. The punchy Melon Cake, inspired by the watermelons covered in fat-free whipped cream that Lovato used to receive on her birthday in lieu of actual cake, is about seeking the control she lacked for so long. And California Sober, a strummy mid-tempo, explains where Lovato is with her recovery today.

“I haven’t been by-the-book sober since the summer of 2019,” she said. “I realised if I don’t allow myself some wiggle room, I go to the hard [expletive]. And that will be the death of me.”

Braun said he and Lovato don’t agree on everything, but he’s urged her to think of herself as a “real model,” rather than a role model. “You want to tell the truth. And you’re constantly learning,” he said. “No one can live up to the expectation of perfection.”

In many ways, Lovato has always shared more of herself outside of her music than inside of it — something that is changing with her new album, particularly as she wrote from a more queer perspective. “When I look back at music in the past that was more hesitant to be as open as I am today, I feel like I just robbed myself of vulnerability in some of those songs,” she said.

Talking about the broader changes in her life, she sounded peaceful, though her journey is far from over: “I’m ready to feel like myself.” She smiled. “I’m finally being honest with myself.”

The New York Times News Service