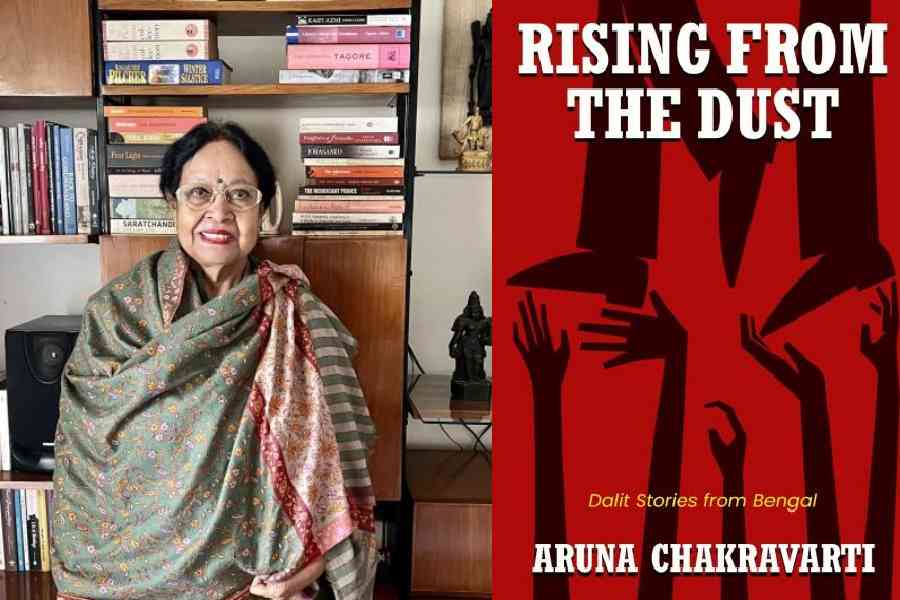

Dalit literature has been hitting the global headlines. This interview with Aruna Chakravarti testifies to the growing global importance of the topic.

Your adeptness in the field of historical fiction has made you a respected and very well-read author. What was it like to move to translating Dalit voices from Bengali to English? Is the Dalit dialect very different from Bangla? What was your biggest challenge?

It was a totally different experience. Moving from creative writing to translation has always been a refreshing change for me. Since my novels are all research-based and carry with them the usual load of anxiety and tension regarding historical and social authenticity, I tend to go back to translation every now and then.

After writing The Mendicant Prince, which involved intense research and analysis into 19th century Bengal’s social history, the family history of the Bhawals, and legal and medical records, I was exhausted and decided to take up a work of translation. I decided to get together an anthology of stories focusing on the plight of Dalit women. It has given me a sense of fulfilment I’ve seldom felt before.

Coming to the latter part of your question. No, the Dalit dialect is not very different from Bangla. Though there are innumerable dialects in Bengal, based on different parameters — religion, caste, village, rural versus urban locales, etc. — the essential language is ordinary Bangla. There were many varied dialects in the stories selected and it was a challenge, a big one, to render them into English. I tried to find suitable equivalents in the English language. I tried London Cockney, Indian pidgin and even the lingo spoken by slaves in American plantations. But not one worked. Ultimately, I decided to make my characters speak the simplest possible English liberally sprinkled with Bengali words.

How did the idea of quilting together Dalit stories come upon you?

The idea came to me after reading a biography of Rani Rashmoni. Dalits have suffered humiliation and oppression from time immemorial, I thought to myself, and the world has woken up to it today. A lot is being written about their plight. But can their sufferings be looked at in a homogeneous light? Wasn’t the Dalit female doubly afflicted on account of her gender as well as her caste? How much of her subjugation and torment is reflected in what we read today? If Rani Rasmoni had to suffer the indignities she did because she was a Shudra, how much worse must it have been for the ordinary woman of her community?

I started looking for stories with such women at the centre and was able to find some excellent representations of the Dalit woman’s dilemma by both Dalit and non-Dalit authors. Unfortunately, many of the stories had not been translated into English and were, therefore, inaccessible to an international readership.

The stories have stunning metaphors and descriptions. There is so much richness in the language, even in translation. Did you have to do any research on the special component of the Dalit voice?

Not really. I like to tell myself and my readers, of course, that I don’t translate. At least not in the conservative sense of translation, that is word by word and paragraph by paragraph. That has got me into trouble, once or twice, with translation purists. But I have my own style and I do my own thing. I transcreate. I read each line of the source text a number of times and try to internalise, not only its meaning but its spirit, the voice of the writer, the special cadence and flow of the language, then express it in my own words. I make it a point not to leave anything out. But I do take the liberty, sometimes, to change the placement of paragraphs and sentences.

The richness you are talking about was there in the original. All I have done is express it in another language. There used to be a theory that English translation can only be done by a person whose mother tongue is English. That myth has long been exploded. A good translator not only has to be proficient in both languages, but she has to have intimate knowledge of both cultural traditions.

What disturbs you most about the stories you’ve translated? Poverty or sexual abuse?

Poverty is a given in the lives of the lower castes and classes in Bengal as represented in its literature. However, poverty is a much lesser evil. The soil of Bengal is fertile and varieties of wild fruits, tubers and greens can be found in the forests and along the banks of rivers. There are many waterbodies which teem with fish in certain seasons. So, food is not very difficult to access. But women, with their instinct for nurturing and in answer to societal expectations, give their husbands and children whatever is available, keeping only the leftovers for themselves. This leads to severe malnutrition in wives and mothers.

Where Dalit women are concerned, the biggest abuse they face is their treatment as chattels. Not only by their families but by society at large. A Dalit woman has no rights; not even the right to dignity. In the story The Fortress, the villagers are appalled at the fact that Sarama has inherited eight cottahs of land. Such a monstrous thing is not to be borne and must be taken away from her. All the villagers are on the same page in this.

Rape and torture follow and she is deprived of her land. Abhagi isn’t allowed cremation after death because cremation is only for upper castes. In the story The Witch, Shora, a Dom girl of 10, is branded a witch and driven out of the village because a baby had died after she had set eyes on him. Chandi Bayen has to follow her father’s profession of burying dead children and is stigmatised for the very job she is forced to do.

What made you choose these stories? Did you have any special criteria?

No, I didn’t employ any criteria as such. I wanted my anthology to include the work of classic Bengali writers like Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay and Mahasweta Devi. But I also wanted my readers to hear the voices of contemporary Dalit writers like Bimalendu Haldar, Monoranjan Byapari and Manohar Mouli Biswas. My selection is a mix of both.

Dalits are not a homogeneous lot. They belong to different groups based on the caste professions of their ancestors which they are forced to follow. There are, among them, scavengers, tanners, grave diggers, snake charmers and handlers of the dead in cremation grounds. There are some religious sects that, though not considered untouchable, also fall into the Dalit category. Among them are itinerant bauls, homeless, rootless Vaishnavs who live on alms, and the poorest of poor Muslim peasantry. I wanted to represent as many of these groups as I could. Hence the inclusion of Mahasweta Devi’s story Talak, Prafulla Roy’s Nagmati, and Tarashankar’s Raikamal.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of of Dance of Life, and co-author of Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College.