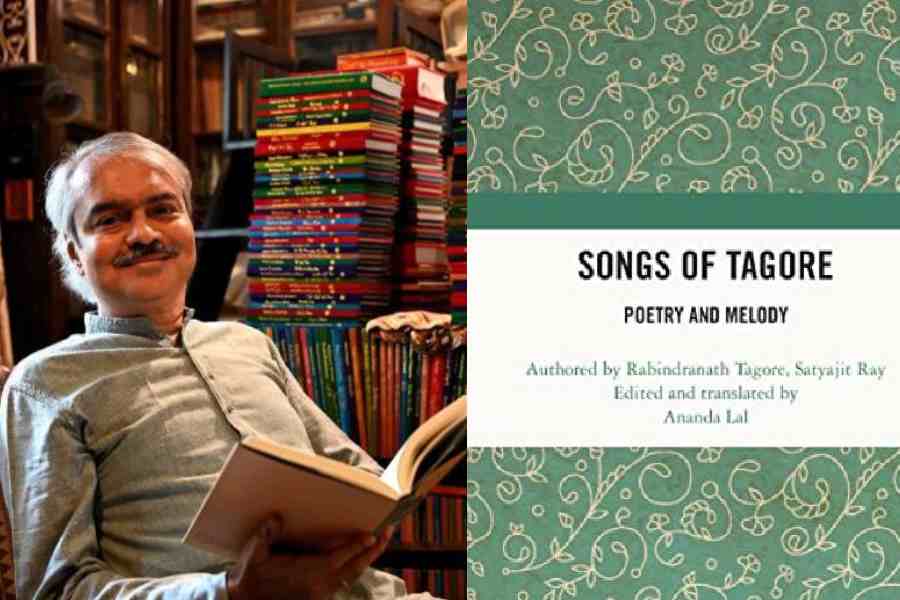

Professor Ananda Lal, eminent theatre critic, academician and translator, needs no introduction. His latest book, Songs of Tagore, provides a comprehensive translation of the songs of Raktakarabi, Tapati and Arup Ratan, as well as features a translation of Satyajit Ray’s essay on the subject, translated into English for the very first time. t2 caught up for a chat.

Songs of Tagore has generated a lot of interest ever since its launch. Can you share a bit about the inspiration and journey behind this work on Rabindrasangeet and the translation process involved?

I have always felt the need for some kind of contemporary introduction to Rabindrasangeet for the non-Bengali. Not that the Bengali knows everything about Rabindrasangeet, because in the book even the Rabindrasangeet-knowledgeable person will find things of great interest. But for such a phenomenon as Rabindranath to go unrecognised internationally for this particular artistic form — just his songs, I mean — is really very unjust and quite embarrassing for us who value Rabindrasangeet so much. So, it has always been on my mind that I should do something for the English reader, and the reader outside Bengal. The book also has my translation of Satyajit Ray’s essay (Thoughts on Rabindrasangeet) which I feel is a very powerful account of the historical and musical background to Rabindrasangeet. It has never been translated in full into English before. I was also aware of the need for accurate scores in terms of transcription, so I had some 40-odd songs transcribed for the book. The number of staff transcriptions of Rabindrasangeet are very few. I felt there should be some redressal of that shortage.

I started with the introduction, which is my own, and then the translation of Ray’s essay, which involved a great deal of conversion of scores and musicological terminology. The 40-odd songs, however, I had already translated for my Three Plays of Tagore, so I put them together with the notations, so that readers and musicians could access the translation as well as the transcription and the transliteration. It was a three-pronged translatorial exercise.

As an expert in theatre, translation, and literature, how has working on this book influenced your perspective on the intersection of these disciplines?

The truth is, it hasn’t. Because this process isn’t something that is new to me. I’ve always been interested in these three things taken together, going back for a good 40 years, so I just proceeded on that basis. The songs he wrote for the plays are part of the play script. When you read a play in class, typically you read only the text of the songs, but song itself is a composite genre. It is poetry plus melody, plus more perhaps! So how can we just treat it as a text on paper? Rabindranath himself said that if you take the music away from the lyrics of a song, it’s like a butterfly with its wings plucked. Only Rabindranath could have used such a beautiful and terrible image to compare the art of a song in its original context, then divorced of that original context, just studied or read as its text. Song is a mixed art form, like film or theatre. Would you study just the screenplay of Pather Panchali without reference to the film? No, right?

You also spoke of Satyajit Ray’s essay a little while ago. What was the process of translating that like?

Yes, for that, it did involve a lot of musical and musicological research. I had to find the right Western equivalents for the Indian terms that he used. This was important because the essay had not been fully translated before, since it’s difficult. But for a succinct introduction to the genre, I couldn’t find a better essay to put into the book. He talks about the folk and classical Bangla song itself, in terms of its history before Rabindranath, so that people can figure out where Rabindranath comes from. And obviously Ray knew his Rabindranath thoroughly. He studied in Santiniketan, and he was also himself an original composer who played around with Rabindrasangeet in his films. So I thought that was an ideal combination to preserve and put out there to the non-Bengali.

The other thing that Ray talks about very outspokenly is that Rabindrasangeet is sung by “mediocrities”. And Ray wrote this in the 1960s, therefore there must have been mediocre singers of Rabindrasangeet then as well! I do feel that this continues today. Rabindrasangeet has become a commodity. Even professional singers of Rabindrasangeet use the harmonium, when we know for a fact Rabindranath himself despised the instrument, and Satyajit supported that. And Satyajit himself was a pianist! What Rabindranath wanted was the esraj but, of course, very few people play the esraj anymore. Satyajit suggested other string instruments like the sarinda and dotara as alternatives. One needs to respect the original composer’s intention, so one must take certain considerations into account to interpret Rabindrasangeet correctly. We need to use Ray’s opinions as a corrective. Let’s try and get back some of the original intent and effect without removing our own artistic interpretation and creativity.

Transcribing and translating Tagore’s songs for a global audience must come with its challenges. Could you share some of the linguistic or cultural nuances you had to navigate during the transcription and translation process?

I’ve been doing this for a long time, and as an academic, what helps majorly is how we use annotations or footnotes. The purpose of the translator is to give the reader and potential artist every context that is involved: full disclosure. The term that I like to use in lectures is transparency. And I pun on that because I talk about myself as a trans-parent of any particular text. Notes help the reader and the artist, with the access to understand the text better.

Your recent address at JUDE’s international conference on sustainability used Tagore as a starting point. Tell us a little more about that.

Take Santiniketan, for example. Back in the day, it was very dry and the Khoai was barren. He began the movement to plant trees. And now you find that Santiniketan is a bit of an oasis and attracts rain. These are things Tagore understood. Maybe it was instinctive, maybe it was romantic, but he practised as well as implemented what he wrote about. Just the fact that he had classes in the open air, makes a child aware of oneness with the natural world. That’s become part of our education. He was a Green pioneer.

Also, besides seasonal songs and plays, his literature itself. What did he foresee a hundred years ago when he wrote Muktadhara? Nobody in the world was talking about the danger of big dams at that time. Tagore criticises dam-building at a political level in that play. And that is exactly what is happening today. Raktakarabi is about excavating resources, about miners digging for gold, which I read as any mineral underground. This man was futuristic. It’s almost as if he was writing science fiction! Those were some of the things I talked about.