Julie Banerjee Mehta was blown away by the honesty and unique style of the 40-something author Manish Gaekwad who recently wrote a memoir, The Last Courtesan, about his mother’s unusual life as a mujra dancer and singer in the Bowbazar kothas from the 1960s till the 1990s.

Irreverent, innovative, brutally honest and hugely compassionate, the memoir is compelling and unputdownable. He tells the story of how his mother was trafficked as a minor at the age of 10, bought under the pretext of marriage from a little village near the-then Poona. Her in-laws, especially her mother-in-law Neeno and her sister-in-law Pushpa were the bednis (traffickers) who sent her to the red light area of Calcutta as a slave girl. The author’s mother, Rekha, and her siblings did not even have a second ghagra to wear when they were menstruating, and for days they ate rice gruel.

Manish is currently in Calcutta from his home in Mumbai, researching his second memoir from his perspective. He has rented an apartment some distance away from his mother’s apartment. “It is a 100-year-old building -- sturdy and with a high ceiling (to count sheep) that isn’t possible in Bombay.” t2 sat down for a chat with him. Excerpts.

Your dedication to your mother comes through vividly in this memoir. What was the process and at what point in your life did you feel you had to tell your mother’s story?

More than me, it was my mother who wanted to tell this story. When I was a child growing up in the kotha, she would narrate incidents and once she even recorded herself on an audio cassette for me to listen to later. In 2018, I wrote an essay about us that went viral and led to a book deal. I went to her during the pandemic years and discussed it. In fact, I first asked her for the audio tape she had recorded some two decades ago. She had misplaced it. So, we began the process of recording her on my phone and this time I was paying attention as a grown-up who understood her, but, most importantly, this process helped us bond, which had not happened as we had lived apart for a long while.

From the start the tone you set in the telling of this story is refreshing and immediately signposts the feistiness and sense of faith your mother and her mother Gullo had in naseeb, destiny. It is as if your mother flew on the wings of prayer and faith and her ability to survive. Did you imbibe that from her, and how has her fearlessness and faith informed your life?

My mother’s philosophy can be summed up in one of her favourite film songs — Duniya mein hum aayein hain toh jeena hi padega, jeevan hai agar zeher toh peena hi padega. She would hum it quite often, almost in a zen-life acceptance of life. If you see the video of the song in the film Mother India, it is a celebration of hardship without overt sentimentality. Nargis carries the plough on her shoulder, a Christ-like figure bearing the cross, tilling the land and providing for her children.

My mother had a very strong instinct for survival. I think it came from her own mother Gullo, who had to raise 10 kids single-handedly in extreme poverty and, sometimes, when a child died of a fever or an accident, there was no time to grieve but to look after the others. My mother thought of her mother as a Mother India figure and now I may have to draw a parallel for her unbounding resilience. Am only following how I was raised, so yes, I owe everything I know of life to them.

She was a woman with a huge heart and vision. Being deprived of education she knew the urgency of providing a bright future for you. And you did her proud as such a compelling writer. Did she ever tell you how you actually met her expectations of you and turned her dreams into reality?

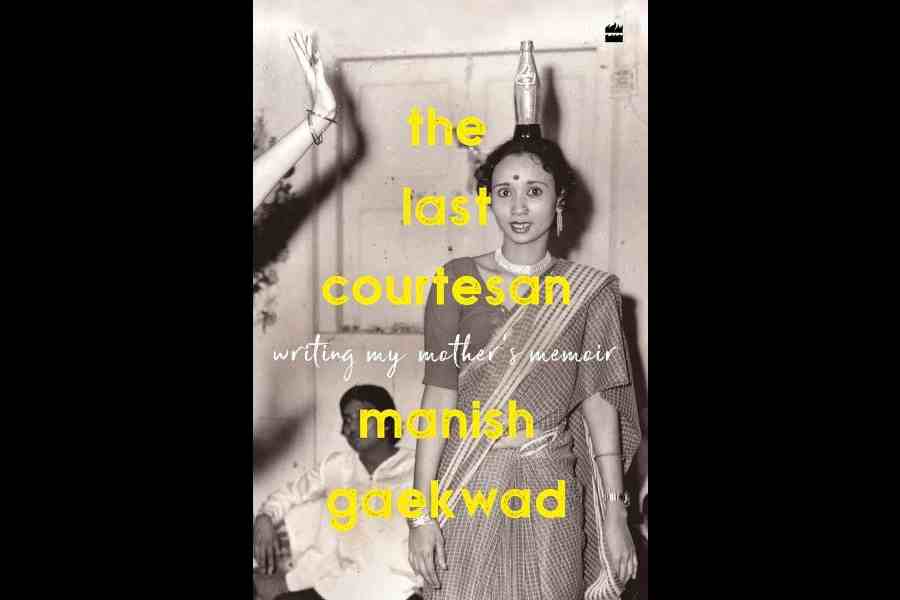

The Last Courtesan – Writing My Mother’s Memoir, with a picture of Rekha Bai doing her signature act of balancing a bottle of Thums Up on her head on the cover

She was once shoo-ed out of a school for peeking in out of curiosity when she was a girl herding goats in Poona. That further piqued her interest in education. If she couldn’t have it, she tried her best to educate her younger brother and sister, but she managed to succeed with me. The thing is, she was a quiet and curious person, who, when denied something, was quite headstrong to acquire it. Even when she was singing and dancing in the kothas, she had hired a tutor to teach her how to read and write in Hindi.

She read a lot of Hindi pulp novels. But she wanted me to be a doctor. She even tried to enrol me for BSc at St Xavier’s College, where I was politely turned down because I didn’t have the grades for it. Since she put me in boarding schools in Kurseong and Darjeeling, I grew up with English as my first language, but, back in the kotha, there was no English literature reading culture. I did not read her pulpy Hindi novels there because I would be secretly reading English-language comics and film magazines.

She was unhappy for a long time when I switched between jobs, selling county liquor in a slum with her sisters in Poona, as a salesman in a clothing store, as an admin staff at The Oberoi Grand, as a call centre executive at Citibank. I did medical transcription in Poona, legal transcription in Bangalore, worked as a fraud-specialist at the GE call centre in Gurgaon, a research analyst in another firm, till I found my way to Bombay working as a writer at Mid-day, later Scroll.in, and then into film-writing for Imtiaz Ali.

It is only when my first novel, Lean Days, was published in 2018, that she finally began to comprehend that I had achieved something, although it still did not yield job and financial security. When she saw her photo appearing with my article in Outlook magazine, she began to proudly show-off to her friends and neighbours that she was no longer invisible, that the world was reading about her, and, so, in a roundabout way, she acknowledged me.

What are your first memories of her?

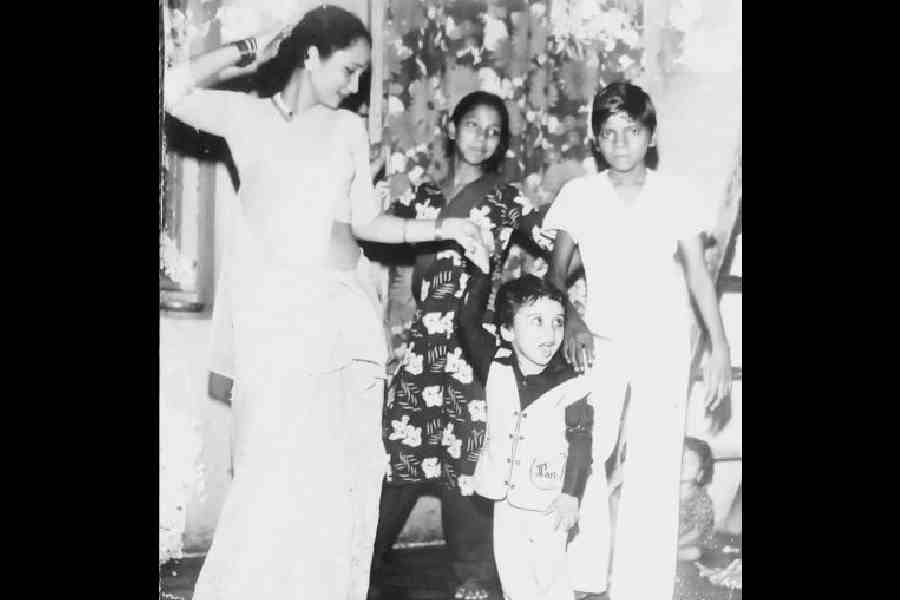

My first memory of her is violent, of her tussle with a man in a kotha, who chopped her finger but she said it was a bad dream. The good dream is me watching her dress-up for the evening mehfil, twirling in her yellow gold ghagra embroidered with a thousand tiny ghungroos that produced the most magical sound I can still hear to date.

What are your first memories of the man you understood as your father?

Oh, I first saw him naked. He was in the kotha, sneaking into my mother’s bed, which she shared with me. To appropriate Shakespeare, I was a child then, he was the father, and now I am the man who remembers it without malice. Once a year, when I returned from the boarding school for my winter vacations, I would insist with my mother to meet him.

Manish Gaekwad

He was generally nice to me, as one should ideally be to a child. It’s only when I grew up and heard more about him from my mother that I understood he was unimportant to us and I went along with it because he really did not in any way fulfil his duties as a spouse, or as a father. It did not make a difference to us as we got by just fine without him.

What was the most difficult thing you had to face in you went to boarding school so early in life in Nursery class?

I went to boarding school when I was five. The first few years were fine. Later, when the children or teachers began asking questions about my family, I had to lie that my father is dead. And I used to say my mother is a stage performer, which was not too far from the truth but I stopped at that and did not elaborate it further. I was a quiet, shy person who spent all his time in the library, not playing games and hanging out with girls. Boys teased and bullied me. And so did some of the teachers. But nothing I found traumatic, perhaps because I have my mother’s indomitable spirit.

Could you speak about how you felt about having no real father — children can be so hurtful and unkind. Could you share any anecdotes about how you encountered questions of your parentage when in school or later in life?

Actually Julie, I haven’t thought about this at all. I was raised entirely by women, who lit the home fires and earned the dough as well. Men don’t run the kotha. Yes, the pimps are around, but they are outside, soliciting patrons. There are of course goons, and policemen, but all of these men are nightly guests for a few hours. The real rearing of a child is done by a courtesan who has her sisters and her girlfriends to fall back on when in need. Boys growing up in the kotha can feel the lack of a father-figure, but I guess I didn’t feel it, or if I did, I saw my mother without a spouse, or her own father or brother by her side. It didn’t affect her. Why should it bother or define me? And in school, he was mentioned as dead, which he was pretty much to us even when alive. So, that was never a prickly topic to debate.

This is an unputdownable story. How did you gather the events? Many sittings with your mother? Did you meet many of her colleagues in the business and talk to them too? Tell us some stories you heard about your mother from perhaps her patrons or ustads or her sisters in the kothas.

The initial idea was to write an account of all the tawaifs I grew up with. But since two decades had gone by, some were dead, some had discreetly moved into mainstream society, some into oblivion. I found a few, but they were unwilling to talk. The children of the tawaifs were also reluctant, as they now had what they called a respectable seat in society. I completely understood, so I did not pursue it.

My mother said, “Yeh sab meri tarah frank nahi hain.” So, that was it then. We decided it would be just her telling her story, and in a way, her story is emblematic of many with similar lives. We spoke, I took notes, recorded, and checked with her throughout 2020-22 while I was writing and editing.

I decided not to cross-check with her ustads and patrons because I believed it should be her memoir, in her own true words, and that’s how I kept it. She was terminally ill at the time, and I had reason to believe a dying person seldom tells a lie, in the way that she was a God-fearing and abiding person all her life who believed in God’s will when it came around to telling me, of all people, to whom she had nothing to hide. In a manner, I became a ‘father’ to my mother to confess.

Your mother loved Meena Kumari. Your mother herself was a poet and lover of Urdu poetry and believed she was Meena Kumari. What was it about her performances and her ability to hold the attention of many that strikes you? When you saw her perform what was it that rushed through your mind?

There was another tawaif next door called Meena. I would say she was the thunder and my mother was the lightning. I would peep through the curtain to watch Meena dance on a brass paraat — her heavy hips undulating like a belly dancer. That brought out the applause from the patrons. Then my mother would dance like an acrobat on a wire, balancing a Thums Up bottle on her head, or bending over her back to collect notes with her mouth, or even doing the gol chakkar, which was like a bolt of lightning. She was an electric dancer, swift and stunning with her movements. Patrons loved it. She had a hip movement of her sitting and rising up. The other tawaifs who saw me imitate my mother when she was not around, would say, ‘Bilkul apni maa ke jaise kulha chalata hai,’ which pleasedme immensely.

Your memoir highlights two of the ugliest substances in our culture — patriarchy and poverty — holding hands in an evil alliance. Do you remember how you felt when you first understood how Ramlal and the likes of his mother and sister Pushpa are the predators who are the criminals that continue to devour young women and perpetrate slavery in our modernising society?

Of course, it is evil. When I heard my mother in detail, it upset me, but she was able to speak without bitterness, and that endearing quality of hers made me marvel at her superhuman ability to rise above the pain, and will no hatred towards another. Not everyone can do that.

You also have revised the stylistic elements of the English Language as James Joyce had done in Ulysses. Almost on cue to what the grandfather of postcolonial writing had suggested in the foreword of his novel, Kanthapura, in 1936, you have created a new style, a new language that is a chutneyfication of English, Urdu and Hindi, much like the mango pickle your mother so loved. You use the vernacular and the English language with such ease and aplomb. Love the spiritedness of new ways of telling the story innovatively. Did you consciously work on the way language is used in this work?

Ha, ha, that’s sweet of you to say but I dare not. I remember once long ago, on the beaches of Goa, I pulled out Joyce’s Ulysses to read. My friend threw it in the sea. I suppose it’s still sailing somewhere, in search of a loyal reader. The only thing I have been conscious of is to keep my mother’s voice as authentic as possible. So that’s why the mix of so many dialects makes this book’s language Indian, unlike the Queen’s proper English.

This is a book those of us who grew up in Calcutta and love this city must read. The close references to Ma Kali Temple are very powerful, and your mother’s faith in the Goddess Shakti earned her the blessings that helped her succeed in many crises. Tell us more about Calcutta and its strong influence on the memoir and your mother and you.

Yes, she embraced Calcutta so fondly that for years when I insisted she move with me to Mumbai, she refused. I understood — her friends, her patrons, her ustads — whom she considered family, were here. Like you mentioned, her memoir is rooted in Calcutta. Her religious loyalty fluctuated a little bit, but she was quite devout, and would bow even if a stone kept under a tree was smeared with sindoor. Citizens of this city, who love literature, must give it a chance. It will give them an opportunity to know a part of the city, the Bowbazar area, where the kothas flourished till the late 1990s, more intimately than they ever did.

You are now in Calcutta, researching and writing your second memoir from your perspective of your mother. Tell the reader what you feel and like or dislike about Calcutta. What is your memoir going to be like? Which are your favourite places? Do you find Bowbazar has changed?

I grew up in the Calcutta Bowbazar kotha district that is no longer around. Old baaris have been demolished or lie in ruins. So, my childhood has either been wiped-out or is in tatters. My memoir of my childhood years in the kotha are permanently lodged in my head. That’s where the research is, to return back in time, and recreate it as honestly as possible. I have no complaints about its physical appearance, or rather, disappearance. I don’t romanticise the past. I live in the present. Personally, I am a tourist in Calcutta, and I like it that way, always discovering something new each time I visit. Like even seeing a shiny new corporate building where a kotha once stood. One has to adapt with the times.

Which are the writers who influenced you and what is the kind of music that you like?

Anais Nin, Michael Ondaatje, Albert Camus, Franz Kafka, Anita Desai, W.G. Sebald, Susan Sontag, John Berger, Marcel Proust, Alain De Botton — oh God, the list is too long. Other than rap and rock, I can stomach all of it, although if you ask me pointedly, jazz and ghazal may be my thing.