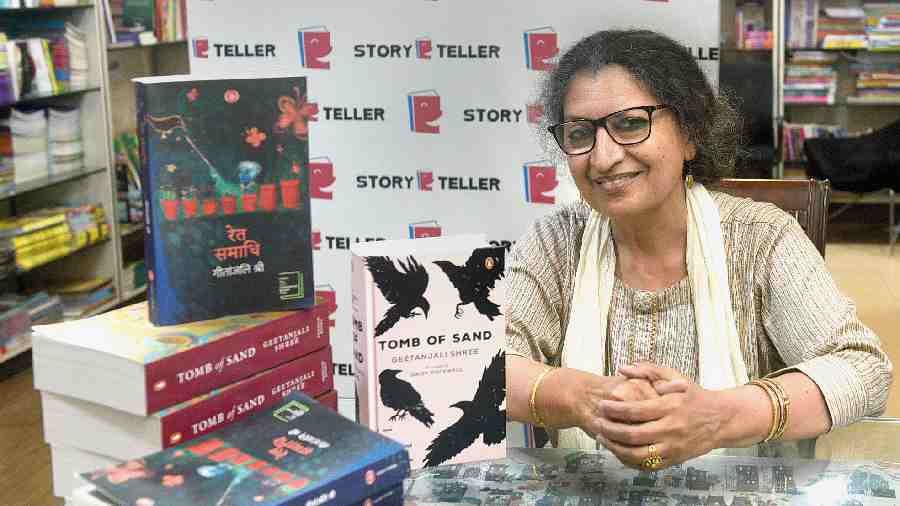

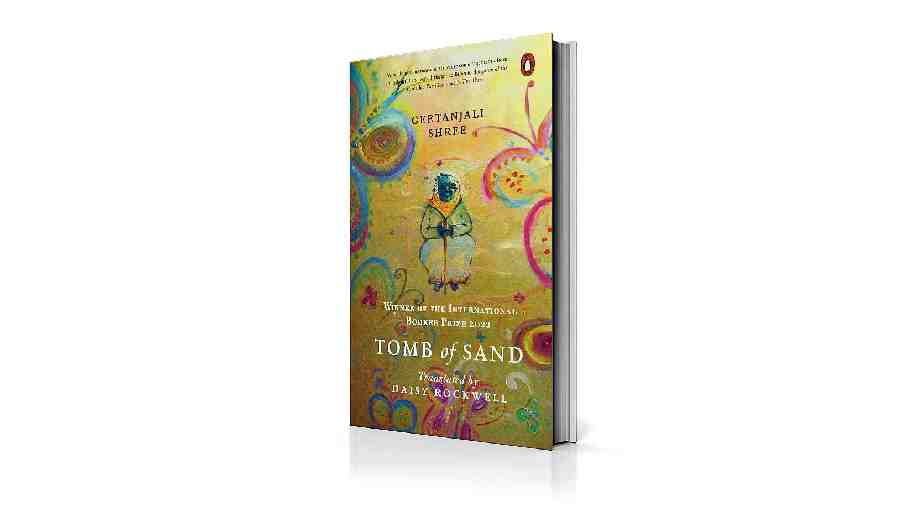

This Hindi Diwas (September 14) couldn’t have been more special for Kolkatans. “I have been reading Ret Samadhi in Hindi and I am enjoying it thoroughly. It’s such a proud moment to have you here amongst us on Hindi Diwas,” enthuses an elderly woman as Booker Prize winner Geetanjali Shree signs her copies patiently. A wide smile flashes on the bespectacled face of the author who came straight to Storyteller bookstore for a brief meet-and-greet session from the airport. She is in Kolkata after around a decade, she cannot remember the exact years, and her demeanour is quite mixed — serious, calm and at times breaking into a smile and at other times wanting to run back to her space and dwell in her world of words. Author of five novels and five story collections, Geetanjali Shree became the first Indian author to win the coveted prize for Ret Samadhi’s English translation Tomb of Sand by US-based Daisy Rockwell. The novel chronicles the transformative journey of a female octogenarian referred to as Ma in the book, after the death of her husband. In this exclusive free-flowing interview the novelist shares with The Telegraph why recognition of all sorts, big and small, are important to her and her Booker moment. Excerpts.

I believe this book and the recognition proves to be a boon for three entities — it brought India back to the literary map of the world; it has given a big boost to Hindi as a language and it has given more confidence to women writers. How do you feel about it?

It’s certainly something to feel happy about that I have been lucky to be the person through whom this has happened. It feels good that I am representing Hindi, representing South Asian languages, and representing women. Of course, I didn’t plan it, but I am very happy that I was chosen by the ‘stars’.

How has life changed post the Booker win?

It has become a lot more public than what it was before, which is a mixed blessing. It’s nice to have a larger community, to have a lot more people care for you and to be able to meet interesting people from different corners of the world, but it also produces some anxiety in me because I need some solitude in my writing. So, I have to balance the public with my private space.

Tomb of Sand’s recognition gives a big boost to indigenous languages, particularly Hindi. What do you have to say about that?

It’s a boost certainly. No literature thrives on its own or because of one book and when something big like the Booker happens, it lights up not just my work but the entire literary world and that world is full of books from various Indian languages, including Hindi. People are interested in translation today because that is the main way to communicate and bring good work to the world. However, it is important that it should not just happen in an excitement for one moment, it should be something sustained, something that should be worked on seriously.

Recognition is not a new entity in your life. What do they mean to you?

Different kinds of recognition are giving extended readership. Celebrated Hindi writers like Manzoor Ahtesham and Krishna Sobti had spoken very encouragingly about it and enjoyed the book. Every reader opens another vista. Because it has come out in English, it has suddenly gained access to a larger world. So, the kind of recognition that I got from this very specialised Hindi circle matters hugely to me; even though it is small and limited. And what I am getting because of the Booker also means significantly huge to me. I would also like to mention that before it came out in English it came out in French by a very fine translator called Annie Montaut as Au-delà de la frontière. Obviously French doesn’t have the spread as English. So that many readers didn’t know it. But that recognition also matters to me.

In which other languages can we expect the book to come out?

It’s just the beginning, I hope there will be translations in all Indian languages and in some European languages as well.

Geetanjali Shree and Daisy Rockwell, who translated Ret Samadhi

Tell us about how the Booker Prize happened?

I have no idea (laughs). A publisher in London wrote to me with an interest in publishing my new book. They had a translator in mind who sent me samples and I got the sense that this person can do it; she has the sense of the language and what I am trying to do and say. So, we worked on the translation and since we ran into Covid years we could never meet before the actual event. We exchanged long emails, as big as the book or maybe even bigger! We met just a few days before the Booker announcement as we were shortlisted.

What was on your mind when you were shortlisted?

Nobody knew who of these six was going to get it. I am not particularly interested in a prize; I am not ambitious in that sense. I was quite calm. Shortlist of course was a big recognition. Shortlist means that these six shortlisted books are all worthy of the Booker. And that itself is recognition. I found out later that it’s a rigorous process; it’s not done at all in a careless manner. They have to read, discuss, tell each other why they prefer a certain book over another, they do it at every step. So, when it came in the Shortlist, for me, Daisy [Rockwell] and my book it was now considered good enough for the Booker. I wasn’t thinking beyond that. The next one was another thing, and it’s wonderful.

How long did it take you to write the book?

I am a slow writer. I worked on Ret Samadhi for around eight-nine years. I stay with my characters, write, leave it, go back, do another draft and the cycle repeats till I finish the book and I am content.

Your book already seems to be drawing the wrong kind of attention and allegedly ‘hurting religious sentiments’. Are you more conscious now as a writer?

Somebody did something which I think was not very informed because there’s nothing objectionable in the book. You can’t take something out of its literary context and call it objectionable. A writer has to follow her own sense of what is good and what is bad. I won’t want to make certain kinds of comments on women; I will be alert about it because it’s against my sensibility and my belief in my value system. A writer doesn’t want to disrespect anybody; a good writer writes to reinstate the dignity of human beings. When it’s completely uninformed and baseless then anything can be picked up and turned objectionable; then I can never know what I should write and what I should not. I might as well stop writing. There’s nothing like to be ‘alert’. I have to be true to myself and sincere to my beliefs and values.

What does the Booker Prize winner do in leisure?

I do a lot of things and sometimes nothing at all. I go out with my family and friends and listen to music sometimes. Also, reading is integral, kitabo se jude hai to kitabon se to rishta hai hi (since I am associated with books so I have a relationship with them).

I hope we are seeing you more in the city and especially during the winters for the literary meets?

I would very much love to be here.

What are you working on next?

I am not getting much time to myself nowadays because of the prize, but I have a novel which I intend to go back to once all these things settle down.

Born in Mainpuri, Uttar Pradesh, Geetanjali wrote her first story while travelling on a train

She did her PhD in Social and Intellectual Trends in Colonial India: A study of Premchand at MS University, Baroda

She has been a professor of modern Indian history

Her 2000 novel Mai was shortlisted for the Crossword Book Award in 2001

Tomb of Sand is the first Hindi-English translation to be shortlisted for the £50,000 Booker prize