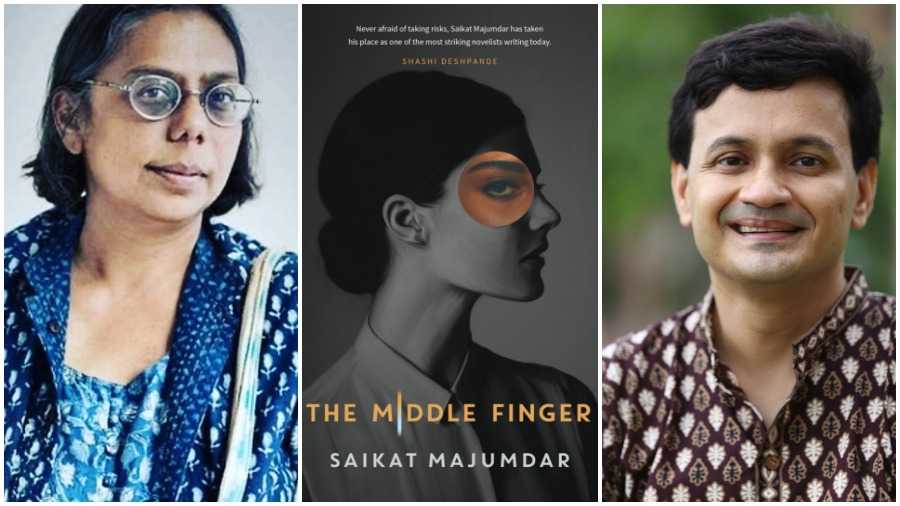

Saikat Majumdar’s new novel, The Middle Finger, is the story of a teacher’s relationship with her students in India and with her own professor in the US. Power hierarchies blur as both students and teachers are seduced by each other’s ideas.

The epic struggle in the novel is the teacher’s journey from being the giver of knowledge to becoming a sharer of knowledge. Gender, caste, class, race, language and lifestyle ladders wobble when the teacher is seduced by her students as they open new worlds to her. But before she can reach her journey’s end, she has to overcome the traditional boundaries of her conditioning as an upper-class urban US-educated woman.

Majumdar aptly foregrounds his novel with dialogues between the great mythical teachers Socrates and Dronacharya and their students Agathon, Arjun and Eklavya. In an impossibly tender end, the intimacy of love overpowers traditional barriers.

I am a professor at New York University and part of the women’s movement, grappling with issues of sex-trafficking and #MeToo every day. I have always found Saikat’s writings compelling, as few authors can weave the story of sex, sexuality and gender with the story of class, caste and education privilege.

I am presenting this Q and A with Saikat in the hope that young readers will find clues to some questions in their lives.

When was The Middle Finger born? Was it triggered by the #MeToo movement?

The movement was definitely in my mind as the novel took shape — especially as it has played out across university campuses worldwide. The structure of abuse it bared was a real jolt, particularly as it has named people I’ve known for a long time — all the way from Stanford to Jadavpur and everywhere in between. However, topical issues tend to linger over my fiction in a misty, dreamlike way, rather than directly. I found myself thinking more about the Gurukul tradition in India, the culture where a student serves a mentor in a self-sacrificial way in order to gain learning and knowledge. Myths have always glorified this tradition, but I wonder to what kind of abuses this tradition must have been open. Obviously such traditions are still quite alive, particularly within the musical and performative arts of India, and even within the regular university.

I experienced a bit of a reverse culture shock after I returned to an Indian university after 17 years in North America as student and teacher. Even with a generation of students who are far more individualistic and articulate than we were, there is a lot of old-fashioned reverence for the teacher, which is wonderful and missing in the consumerist American university, but which also creates a kind of a hierarchical atmosphere that I knew as a student here but which I’d forgotten about. I was quite used, for instance, with students calling me by my first name, but that happens very rarely here, even with postgraduate students. This novel is driven by my desire to tell an Ekalavya story in a contemporary campus, and hence is quite fictional, but many of these social issues in a transnational campus life obviously plays out in it, particularly those to do with power and intimacy between teachers and students — and the issue of who even gets to be a student, who gets access to certain kinds of education. What does a teacher do when faced with these questions?

Your novel uproots the hierarchy of power with intimacy. Is it possible or do we need big structural changes in society for such a thing to really work?

You’ve touched on the idiosyncratic element in this novel. I guess that’s why fiction is always a bit different from history even when it draws so much from it. I wanted to write a story where Drona eventually sides with Ekalavya and abandons Arjun, and does so with a humane and vulnerable kind of love. Wendy Doniger describes a medieval Jain myth where it is Arjun who cheats Ekalavya of his thumb, and when Drona comes to know about it, he accuses Arjun of deception and blesses that a Bhil warrior will be able to shoot arrows using just their index and middle finger. But there is a utopia here. I don’t know if it can really happen — perhaps it can, perhaps not.

But to see this as a structural change would be a dangerous kind of idealism, something that can go wrong easily. I think in reality things are best left to rules and laws that minimize structural inequality — such as to ensure that there are more and more women in institutional leadership. You are right in saying that in this novel the hierarchy of power is uprooted with intimacy. But things that have emotional and artistic appeal can be risky in real life. Every story is unique, and fictions try to touch the uniqueness, but they don’t have to be blueprints for real-life action. Intimacy is a powerful thing. But it’s hard to say when it’s normative, when it’s transgressive, and when it’s destructive.

Does gender fluidity rest on caste and class fluidity?

That’s a great question! But I don’t think it is possible to draw any causal links between these different fluidities. I think people are basically conservative when it comes to these identities, both in a conscious and unconscious way. Vivan Marwaha’s recent research has shown that Indian millennials are rather conservative and prefer arranged marriages within their community. The minority that wants to bend or break rules do so in unpredictable ways, and if your urge to do so is genuine you’re not just following trends. The articulation of such fluidities, or organised activism around it, however, may require a certain cultural literacy defined by education and social position. It might be easier to find queer activism more visibly in upper-middle-class, urban circles, which are also usually upper-class and caste. But queerness itself? That may be anywhere, though often hard to recognise.

Who should set the limits of the relationship between students and professors ? The institution, the teacher or the student?

All three, of course, in an implicit understanding with each other. These can be emotionally invested relationships, and to bring out their best, they must be. But any relationship where one person has institutional power over another should have limitations. A good institution reflects the will of its citizens as well as the limitations within which such will must thrive.

You begin with Drona and the Bhil and end with Megha and Poonam. Are you also crossing the normalized distinction between the teacher and the taught?

Inescapably. There are deviations both in terms of gender and sexuality, from the myth to contemporary reality. There is also the very question about who gets to be a student, what privileges it entails, which is part of the myth too. Class can be powerful deterrent to this eligibility — and that is a barrier here as well, though hard for the liberal protagonist to recognise. Something very powerful, but deeply invisible, has to happen to break these barriers. Not just between teacher and student, but between human beings.

Who is the magician teaching a six-year-old math through tricks on YouTube?

Ha ha, how did that get there? I guess the dichotomy between knowledge as read and knowledge as performed (really and virtually) is a troubling theme for Megha. Primarily the dichotomy is about poetry, but it bleeds into everything, no? And the question of authenticity is the most intense and visceral when it takes on a performing body.

Ruchira Gupta is an Emmy award-winning journalist and activist. She currently teaches at New York University