Kindling thoughts of his raging thirst at sea

Shipwrecked, afloat, drifting aimlessly

When high in the sky an eagle did cry

A lonely speck, as he below

Lost in the tides, in the ebb and flow

A wash in the oceans, wished he could fly

Unfettered, unbound, free from care

As light as a feather, up in the air.

— From Anjana Dutt’s Zaahir and His Quest for the Lost Emerald

Rich and tumbling over with images which capture memory of a fast vanishing past, writer, poet, photographer and artist Anjana Dutt has always been a quiet achiever, pushing the boundaries to create her own stamp in the realm of literature. Her artful use of poetry as a genre for story telling in the traditional iambic pentameter, the same poetic mode used by Shakespeare in much of his plays, brings a refreshing flavour to her experiment with wordsmithing.

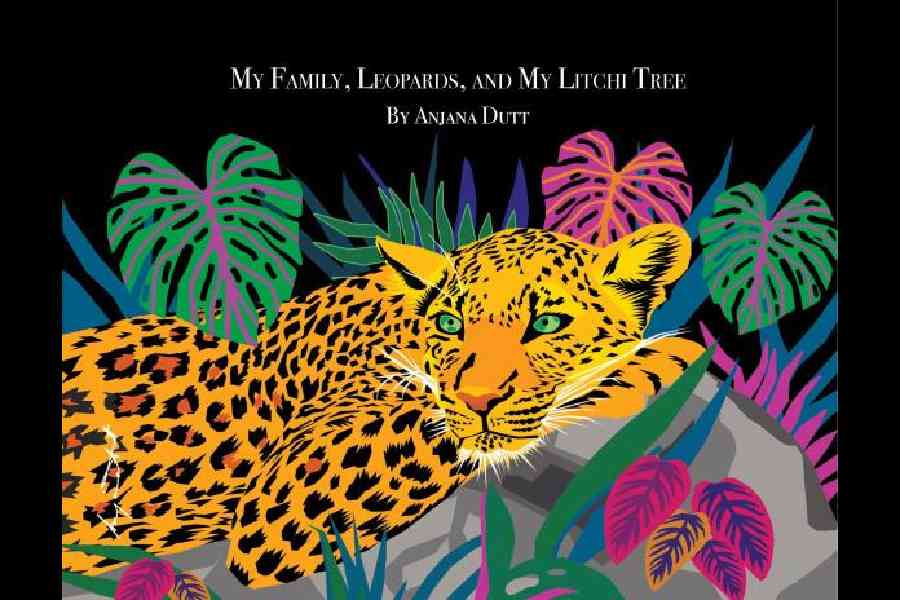

Her ballad style poems like Zaahir and his Quest for the Lost Emerald are upbeat and take the young reader and the old on armchair adventures to worlds that belong to a hoary past. The influence of Sir Walter Scott as in Lochinvar is coupled with the Oriental colour of Egyptian heroic tales that lend a global flavour to her verse. And she has hit her stride with My Family, Leopards, and my Litchi Tree (Blue Rose Press, 2024).

Dutt wears many hats — writer, filmmaker, graphic designer, published poet and photographer, and a proud single mother. Excerpts from an interview.

What were the sparks that drove you to write this memoir?

This book, these stories and the accompanying illustrations are a testimony to a childhood filled with moments of unbridled joy and adventure... of a child born at a time when the pace of life was unhurried, when the extended family provided the circle of comfort and security that allowed her to live both a rich and colourful imaginary inner life and another filled with enjoyable everyday activities that somehow transcended the ordinary, because she was a bit of a dreamer. When her days were peppered with moments of happiness, from simple pleasures like weeding a patch of garden to listening to tales of far off places from a grandmother whom she adored.

My Family, Leopards, and my Litchi Tree by Anjana Dutt

When I began writing these stories, I travelled back quite easily to the child in me, and the world as it was, through her eyes. And I wanted my daughter to read these stories of a childhood so different from hers, so she could share my experiences, and what better way to do that than illustrate them in the colours of a child’s imagination, when most things appeared brighter, more wondrous than they perhaps were in reality. Not only did I want her and others of her generation to read of a time that is rapidly disappearing, but also take my friends and others of my generation back to their own childhood far away from the fast pace we now live in.

Compared to our single unit families, how would you say you were richer than most of this generation or the millennials?

A large number of people of my generation lived very similar childhoods, within extended families, went on vacations together, mostly to holiday homes in cooler places, far away from the heat and hustle and bustle of their daily lives. The presence of grandparents and aunts, uncles and cousins gave them both a sense of security, and love, and perhaps taught them early of the importance of ‘family’, its values and gave them less time to be lonely.

How do you think you managed to juggle the world at school with the world when you were home?

To begin with, by the time I joined Loreto House convent, I had begun conquering my fear of English and to my delight I found a few kids who were from similar backgrounds and I felt less out of place. My home was bilingual, because my mother, though Bengali, was unfamiliar with the language having been brought up in Lahore and Karachi in undivided India. So, English became the language of communication between my parents though she encouraged us to speak in our mother tongue. I spent so much time with my grandparents, who were more comfortable with Bengali, that it became the language that I picked up first.

Your Dida was a sizable influence in your life. Any titbits you could share about her?

Dida was definitely my hero. Her strong personality seeming larger than life to my diminutive self! She was remarkably open-minded when it came to my brother and I, perhaps because of her extended travels to several countries. Though elegant and graceful in her starched cotton saris and Chanel No.5, she was surprisingly well grounded. One of her life lessons was to be ‘prepared’ to tackle all eventualities, because “life may not always be a bed of roses”. She was deeply religious in that she believed that whatever happened to one was preordained by Brahma, and though one may rail against misfortune, eventually one gained strength from untoward incidents. Despite being surrounded by wealth, she valued strength of character above all material possessions. These values and more have certainly helped me maintain my equilibrium, despite facing the challenges of a single working mom.

The synaesthesia is so striking in your narrative, especially in the geographies you write about. Do you think advertising gave you the skills and subconscious training to capture nuances?

I have always been a visual person, in that art and photography have held my attention and fascinated me from an early age. I would pour over National Geographic and Life magazines as a kid, taking in the brilliance of colour in the natural world, and the play of light on objects that lifted them from the ordinary to something imbued with mystery.

I attended a lot of art exhibitions and spent hours at museums through my growing up years, both in India and outside as my parents were keen aficionados of the fine arts. Though I never had any formal training in art, perhaps I inherited my visual skills from my Dida, who was an artist, and my father, who was a skilled designer in the field of mechanical engineering.

Advertising helped me develop my skills as a graphic artist, but the industry had its limitations in that every stroke would necessarily have to enhance the marketability of the product or service being advertised! There was little or no freedom of expression.

After becoming a mother, I developed a few characters and storylines to keep my daughter engaged, and to come up with creative ways to entice her to eat rather than play! Reading to her at bedtime was never enough. She needed original stories that she could relate to easily.

What do you like about facing the tabula rasa — a white sheet of paper with nothing on it?

The excitement of starting to write a piece of prose or poetry; if it’s based on imaginary thoughts, is very different from writing about incidents that have occurred in my life. The former is perhaps more intriguing because I don’t know where my thoughts will take me. I subconsciously draw upon images and words from what I have read or seen, and imagine myself experiencing the unknown.

Writing these stories was very different. I was putting down on paper, what I had experienced as a child, all very real and relatable. Even as a kid my thoughts were influenced by what I read, so a gecko on a brick on our front lawn took me to sunny Corfu alongside Gerald Durrell and I would look at it with part curiosity at its ability to change colour and its love of eating insects with a deft flick of its tongue and part terror (in case it jumped on me). I would say that my stories are layered, and not just a recounting of incidents, but an amalgamation of my imagination as a child and my perception of colour and sound and taste.

I have in fact written a series of poems perhaps best described as hero sagas, in my attempt at experimenting with the iambic pentameter, centered around an imaginary character named Zaahir, the Price of Armenia.

What is your process of writing?

I just pen down my thoughts as and when they appear, though I am at my most creative after dark when the outside world ceases to disturb my train of thought.

I am used to writing to order when it comes to work, but that is a wholly different kettle of fish! Since I am a graphic designer as well as a copywriter I have the liberty of ‘designing’ my copy to fit the brief while keeping in mind the visual element of the brochure or catalogue I am putting together.

Why did you choose non-fiction in this third book?

All three books I’ve written or had a hand in putting together have been non-fiction. The first, Professor Extraordinaire is a collection of letters and messages extolling the values and positive influence of V.L. Mote, PGP chairman, IIMA. The second is a biography of an industrialist titled I Did What I Had To Do, tracing the life and philosophy of a brilliant self-made titan of industry.

My poetry on the other hand, some of which has been published in a journal of international poets titled Prosopicia, in a couple of their volumes, is entirely fictional.

How do you think of yourself as a single mother?

I revel in being a single mother, though being both parents in one, and a good and bad cop has its limitations! I am pretty close to my daughter and not being a particularly traditional mom, am the go-to person for a whole lot of her friends, through school and later as they embarked on their own adventures in the young adult world. I draw upon my own experiences, some good some very difficult, when talking to them or listening to issues that plague them.

My daughter Ayesha, who is an artist — a painter and ceramic sculptor — keeps me on my toes both mentally and physically as she herself navigates the adult world. She studied at Loreto House and, later, Art at National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, and Srishti in Bangalore, and is now a fairly well established abstract artist.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life and co-author of Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College.