Anindyo Roy, professor emeritus, Colby College, Maire, US, has just published his first and very innovative novel, The Viceroy’s Artist. Invoking Lear’s endearing genius for writing the most trenchant and touching nonsense verse that even inspired Sukumar Ray, Roy’s persuasive tale paints an alluring portrait of a highly intelligent, challenged and popular English humorist, writer and artist of the 19th century who came to India on a commission to paint the Kanchenjunga for the viceroy, Lord Northbrooke.

Based on Lear’s journal on his travels in India, the book is a humdinger for keen literature and history buffs with an interest in travelogues by young British writers during the Raj. Over high tea — salmon sandwiches, scones, strawberry jam and clotted cream — t2oS spoke with the author who has made Calcutta his home but shuttles to Maine and the hills of Kalimpong, where he works on livelihood projects for small farmers affected by climate change, and on making education accessible to the underprivileged children of his neighbourhood there. Excerpts.

Tell us about your earliest memories of your mother reading Sukumar Ray’s book of nonsense verse, Abol Tabol, to you. What do you remember about your mother and your childhood?

My mother, Meena Roy, was a shy, withdrawn woman who spent most of her day reading. At that time, we lived in Birmitrapur, a small mining town about 30km from the steel city of Rourkela in Odisha. The limestone mines were owned by Bird & Company. My earliest memory of her is of watching her run her fingers very tenderly over the hardbound Bangla novels that my father would carry back from Calcutta. Over time, she amassed a large collection of these Bangla novels — from Tarashankar to Ashapurna Debi to Shankar — that she would painstakingly cover in shiny brown paper, label and stack neatly on the shelves. I still have some of her collection of those novels that are sadly, and slowly, crumbling away.

I also remember the cover of the hardbound edition of Abol Tabol from which my mother would read aloud Sukumar Ray’s nonsense poems. Incidentally, I also learnt to write Bangla from the pages of Abol Tabol — copying the words in a notebook. In fact, Abol Tabol served as my introduction to the written language! I must have been about seven. My mother was concerned that I did not learn Bangla in school. So, I could be encouraged to learn it by reading nonsense poetry. Although even now I do not write in Bangla, I still read Bangla fiction every time I get a chance. Very recently, I have been going over the stories of Lila Majumdar from my mother’s collection of books.

Your father was the chief medical officer at Bird & Company. How was your understanding of the challenged and underprivileged shaped by his own fashioning of baby creche or childcare for working women?

As the chief medical officer at the main hospital in Birmitrapur, one of my father’s main duties was training staff to run the creches that had been set up for the infants of adivasi women miners. As a young boy, I witnessed his dedication and the fortitude and patience with which he faced the challenges, which included dealing with union rivalry, lack of adequate staff and resources, and differences with the company’s management. But he rarely gave up.

Many, many years later, in 2007, I set up a winter camp that brought students from Colby College in the US to spend four weeks with students at Gandhi Ashram School in Kalimpong. The programme’s main objective was to create an interactive learning environment — for students from Colby as well as the students attending Gandhi Ashram who mostly came from the families of tenant farmers, road construction workers, and daily wage earners.

As the co-director of the program, I got involved in mentoring students, meeting their families, and setting up a sponsorship programme that would enable them to pursue higher education after they completed school. You could say that some of the dedication that I witnessed in my father shaped the way I went on to develop this program over the years, including introducing educational counselling among first-generation learners, offering them donated laptops. In some cases, I also raised money to buy violins that would be offered to specially gifted students.

The most immediate inspiration for this kind of work came from the Late Father Edward MacGuire, the Canadian Jesuit who set up the Gandhi Ashram School in the early 1990s. Meant originally as a shelter for the children of day workers (also called coolies) it grew into being a school with music at the core of its curriculum. Children at that school learnt the violin, viola and cello from the early age of six and trained to play in orchestras in other Indian cities as well as abroad.

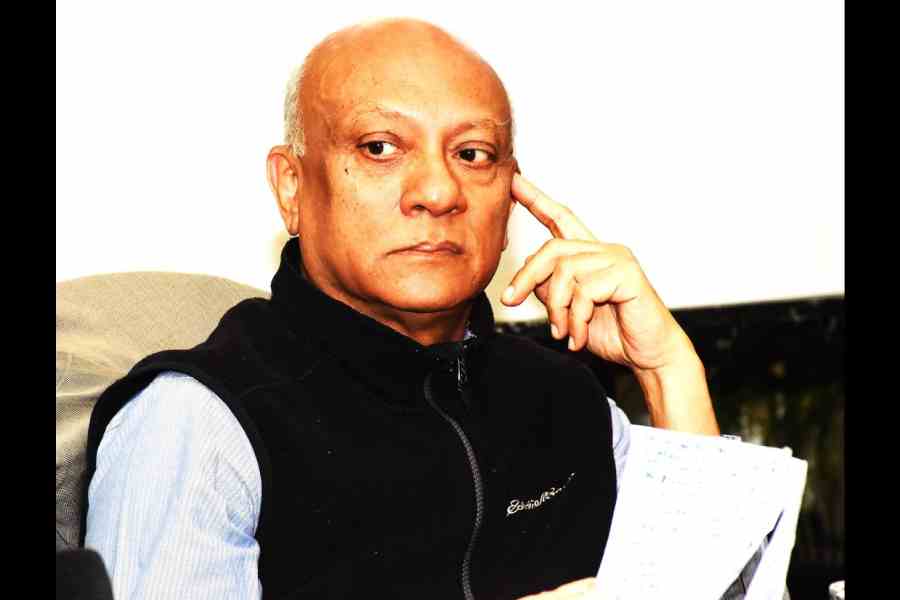

Anindyo Roy

Tell us about how you set up the educational programme in Kalimpong.

The story of how I set up the program began in September 2005. I received a young first-year student in my office at Colby who handed me a letter that I, along with my colleague in music, Steven Nuss, had written to Father McGuire six months ago about setting up the winter programme at his school in Kalimpong. That letter, in turn, had been handed to the young man, Ratul Bhattacharyya, who met me that day, by Father McGuire himself when the former visited the school that summer.

Ever since he was young, Ratul would be sent by his parents to Kalimpong every summer to spend time with his grandmother, a retired doctor who had made the town her home. (Incidentally, she happened to be the aunt of Kiran Desai and her house provides the setting for The Inheritance of Loss.) Announcing that Father McGuire had passed away a month after he received the letter from him, Ratul assured me that in the absence of Father McGuire, the grandmother, Dr Indira Bhattacharyya, would help us set up the programme.

When I visited her during my trip back to India, Dr Bhattacharyya hosted me and showed me around, introduced me to the new director who had taken over the school, and we jointly worked out the logistics, including identifying where the students would stay and what kind of programme would appeal to the rural students of that school. That is how it all began.

When you came upon Edward Lear’s journal on India, what attracted you to the idea of fictionalising this journal? Tell us the likeable bits about Lear?

Lear had been commissioned by the viceroy to do a painting of the Kanchenjunga. He made his way through India to reach Kurseong in the bitter winter cold. Soon after I discovered Lear’s Indian journals at the British Library, I wrote a scholarly paper on his first encounter with the Kanchenjunga. I wished to develop the paper into a book but found myself unable to move beyond what I had elaborated in the essay.

After nearly three years, when I laid my hands on the original hand-written journals of Lear at Harvard’s Houghton Library, I was struck by the poet’s handwritten sentences, and by how long segments were crossed out, some sentences marked by a series of dots and dashes and ellipses. These gaps and interruptions intrigued me. It was then that I first contemplated writing a fictional account of Lear’s travels by filling in those ‘gaps’.

My initial hesitation about my ability to write fiction was dispelled by my colleague at Colby College, Sarah Braunstein, herself a fiction writer, who suggested that the only way to get beyond my writing impasse was to resort to fiction. And given the fact that I could not get those journals out of my mind, I knew I had to do something. Sarah also knew that I had been drawn to Lear’s troubled and confused ruminations about the Himalayan landscape but also to his doubts and uncertainties about being capable as an artist to adequately represent the grandeur of the Kanchenjunga.

So, writing a work of fiction from a travel account was thrown to me literally as a challenge. Around this time, I had already built for myself a small house in Kalimpong, a region that Lear visited in 1874. Living there, my sensibility had already been attuned to the Himalayan landscape, to the hazy world of mist and shadow, of blurry lines alternating with shafts of glorious light. So, when during the three-month pandemic lockdown of 2020 the world went still and it was impossible to step out, I found myself writing, and writing furiously.

The first thing I noticed when I began writing was that my world of the Himalayas was beginning to filter through my consciousness and enter the mind and imagination of the protagonist, Edward Lear. I began the story in media res — not at the start of the real journey in Bombay, but at the beginning of another journey as he sat, in that bitter cold, facing the Himalayas, trying to sketch the elusive Kanchenjunga.

As I kept writing, that initial moment of doubt and hesitation that I had seen in his journals provided a guide to trace the main storyline — about a complex man, both delighting in the public world he experiences through hearing, seeing and smelling the world of India, but also expressing doubts about the English presence in India. At a personal level, that initial moment set the tone for exploring Lear’s personal journey by evoking the memory of his difficult childhood and of his failed adult relationships by dramatising Lear’s thoughts about art and life, about the materiality of colour and light.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life and co-author of Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College