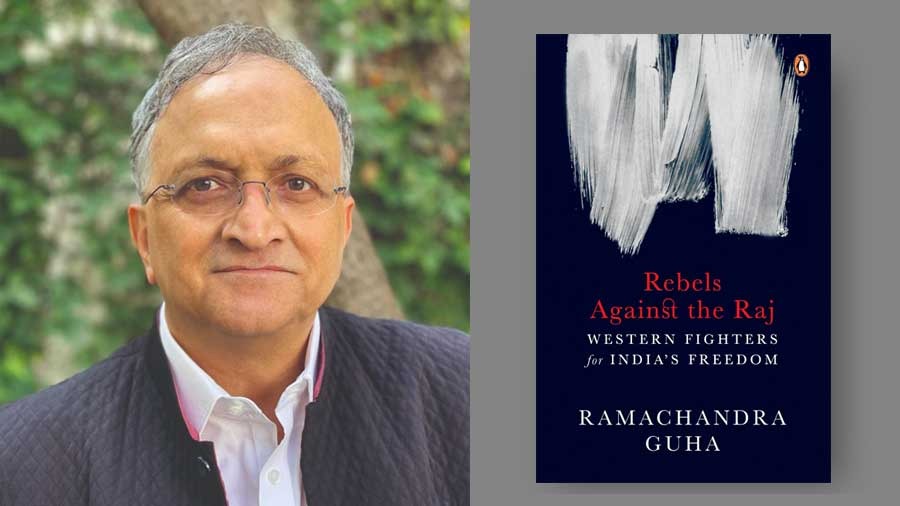

Ramachandra Guha’s latest work, Rebels Against the Raj, tells the stories of seven extraordinary westerners who stood up against the might of the British Raj in favour of India’s struggle for Independence. These foreigners from Britain, America and Ireland came to India and made it their own land, courted arrest, were unceremoniously thwarted and deported by the British government in India, yet went on to do pioneering work in politics, social reform, journalism, education, women’s rights, environmentalism and more.

My Kolkata dialled the writer-historian to know more about his book and his seven renegades — Annie Besant, B.G. Horniman, Madeleine Slade (later Mira Behn), Phillip Spratt, Samuel Stokes (later Satyanand) Catherine Heilemann (later Sarala Devi) and Dick Keithahn.

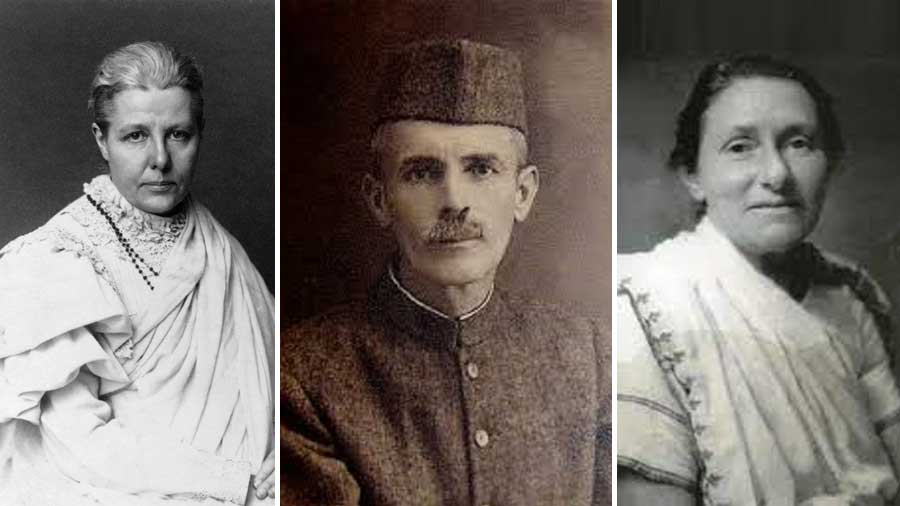

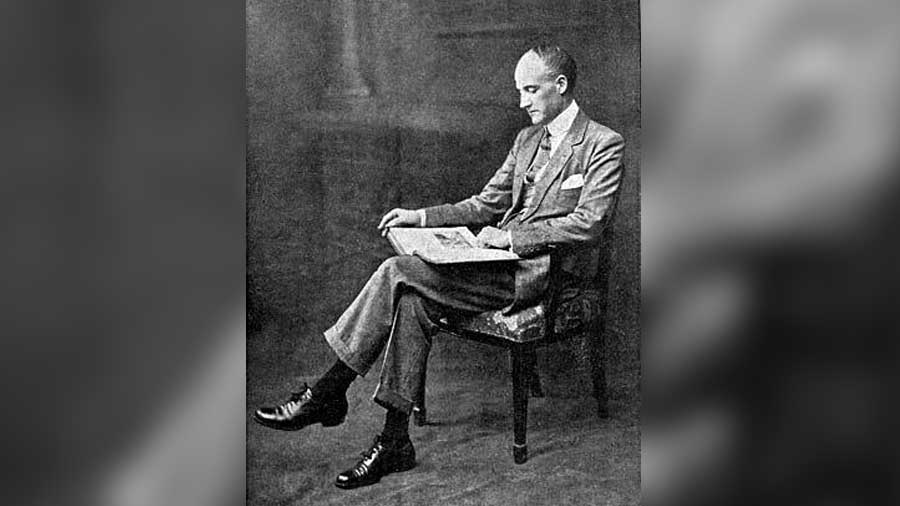

Annie Besant (left), Samuel Stokes (centre) and Catherine Heilemann are three among the seven foreigners Guha focusses on

Before we talk about your new book and the many ideas that come out of it, I have a much more burning question — how were you in history in school? Did you score 100 on 100?

Ramachandra Guha: (Laughs) I never studied history! I majored in science in high school, so after Class VIII, I did not study history formally. My degrees are in economics and sociology. While doing my research for my Phd in sociology, it turned from being field work-based to archive-based and that’s how I became a self-trained historian. Of course, sociology and history are closely allied fields, so the transition wasn’t that difficult. Essentially, you know, what it involves is really very long hours in the archives and I greatly enjoyed that.

(Pauses, thinks a bit) There is still a little bit of a sociologist in me, if you read my writing… but there’s nothing of the economist (laughs). If I may say so, this is not unusual, for people with training in one discipline to contribute in a linked discipline. Many of India's top biologists are actually trained in everything else. (Molecular biologist) Venki Ramakrishnan, who won a Nobel Prize (in chemistry), actually did his first Phd in physics. Sanjay Subrahmanyam, a great historian on mediaeval India, studied economics. And I never thought I’d be a historian, I never even thought I’d be a writer!

Oh, but I read somewhere that at Doon School, you edited a publication called History Times along with the writer Amitav Ghosh….

Yes, that is correct (laughs). But there were other editors too, among them was Gautam Mukhopadhyay, who became a very remarkable diplomat. He was India’s ambassador to Afghanistan, Syria and Burma — three very difficult postings. That magazine was initiated by a retired ICS officer called Arthur Hughes. He belonged to the Bengal cadre of the ICS and after Independence, he stayed on. He was our schoolmaster. One of the first books he gave me was by Ruskin Bond, on European mercenaries in the 18th century in India called Strange Men Strange Places. So yes, I suppose some of the history may come from that. Of course Amitav’s books have a great deal of history. (Laughs) So I suppose we should thank Arthur Hughes.

‘Strange Men Strange Places’ by Ruskin Bond — one of the first books Guha received from his schoolmaster at The Doon School

You said you enjoyed your time in the archives. Is that where the idea for Rebels Against the Raj came to you, while researching your Gandhi books?

Actually, it was long before I came to Gandhi. Very early on, I had written a biography of Verrier Elwin, who was an Englishman who became an Indian and worked with the Adivasis. I have had an interest in eccentric foreigners who worked in India. Elwin identified with India, married an Adivasi girl, became an Indian citizen but never went to jail. He came here in 1927, so he worked with Gandhi quite early but he never had the chance to go to jail and he was slightly envious of his friend Mira Behn (one of the “rebels” in this book) who had courted imprisonment.

I have always been opposed to xenophobia, the idea that one culture has all the answers. I started writing the book after I finished my Gandhi biographies, but the idea was there for a very long time.

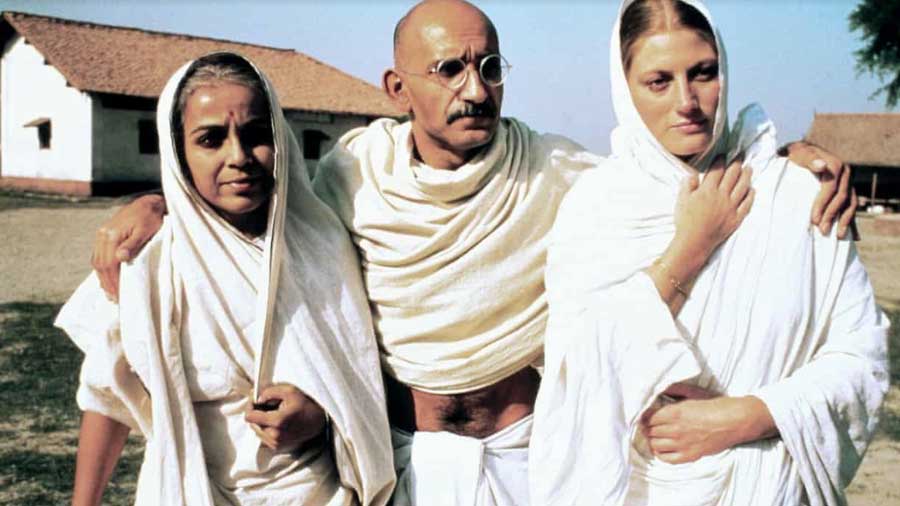

Geraldine James, right, as Mira Behn (one of the ‘rebels’ in Guha’s book), with Rohini Hattangadi and Ben Kingsley in a scene from ‘Gandhi’ (1982) Allstar/Columbia

I chose only those who either courted imprisonment or were deported

There were many westerners working for different causes in India around that time. How did you pick your seven renegades?

To make the project more manageable and to give it a focus, I chose only those who either courted imprisonment or were deported. In my Prologue, you’ll see I have mentioned Sister Nivedita, C.F. Andrews and others, but they were bridge-builders and not rebels.

What was the most startling or interesting discovery you made while digging into the lives of these seven?

Oh, lots and lots! I found all of them interesting, unusual, reckless, daring and independent-minded…

My favourite part was when (journalist) B.G. Horniman tries to slip back into India after being deported for his anti-Raj activities.…

Yes, yes absolutely, that is a great story and I am glad to be able to tell it. It shows how desperate he was to come back. And though I don’t have the evidence, I speculate that apart from political commitments, love of Bombay, love of the national movement, there may have been a personal lover in Bombay too. He was so desperate, and so ingenious in his methods!

B.G. Horniman, editor of The Bombay Chronicle

The leaders of our freedom struggle were not narrow-minded xenophobes

This book spans a century — from 1893 when Annie Besant came to India to 1984, when Dick Keithahn died. How unusual was this aspect of our Independence movement that we not only accepted but looked up to outsiders?

That was how we were then. India was sure of itself, didn’t have to prove its nationalism by pouring abuse on foreigners or by demonising foreigners. We were ready to accept them, honour them, take them for what they were and listen to some of the criticisms that they had to make. That’s what the leaders of our freedom struggle were like. They were not narrow-minded xenophobes. It’s a great credit to the Indian freedom movement and to the climate of opinions in India at that time that these people could make it their home, sometimes marry Indians, do interesting work and be accepted and respected.

Would these rebels be able to come and work in India today?

The book is dedicated to Jean Dreze, who is a Belgian-born economist working in India, and there are some others too, but obviously it’s much tougher now.

There is a message that applies to the countries… experiencing hypernationalism

In the epilogue, you say you have not written this book for nativists or xenophobes, though you wish they’d read it…. Who have you written this book for?

These are essentially seven fascinating individual stories, all marked by independence, daring, courage and united by their identification with a country that is not their own. It’s a different way of looking at history. They provide a very new angle into understanding the history of the Raj.

So, (this book is for) anyone interested in history, in biography, in India’s encounters with the modern West and anyone with an interest in reading about remarkable lives.

There is a message, there is a lesson that applies not just to India but to other countries that are experiencing hypernationalism — China, America, Britain…. Essentially it’s a group biography of these seven remarkable foreigners who came to India.

‘I would make a very bad dictator or administrator. I am very much an individualistic person,’ says Guha TT archives

If you were in charge of deciding how history is taught in India, would you change anything?

I’d be disastrous! I would make a very bad dictator or administrator (laughs). I am very much an individualistic person. Though I will say this… once upon a time there was a dominance of Marxism in history and now, we are told we all have to be nationalists and write about the country in a flattering light. And particularly exalt the Hindu contribution to history, which is possibly more damaging than Marxism. Ideological conformity is bad for scholarship. Full stop.

Rebels Against the Raj (496 pages, Rs 799) is published by Penguin Random House India. Read more here