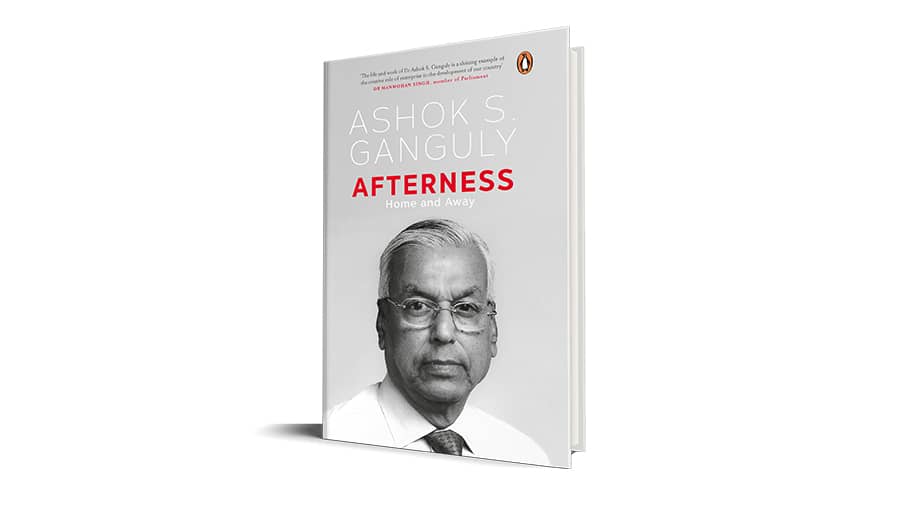

The former chairman of Hindustan Unilever (and also the ABP Group) pens his memoir as a story which spans the 80 years of his life. The narrative encompasses fascinating anecdotes about people in the public eye, while casting a light on some of India’s major events during the 20th century.

This is an excerpt from the chapter titled, Calcutta: 1973–76.

-----------------------------------------------------------

After my brief experience at the University of Kalyani in 1962, I had promised myself that I would never work or live in Calcutta. However, I had to face such an eventuality in 1973. I had just been promoted as the development manager in Bombay, when I was told of my transfer to the Garden Reach factory, in Calcutta. My designation was yet to be announced. In 1973, Kachru, the head of engineering in the Bombay factory, was appointed as the general manager of Calcutta, replacing Bertie Pereira. Bertie and his deputy Datta were transferred back to Bombay, in the middle of a very severe industrial unrest in the Garden Reach factory, in 1973. It also happened to be the period during which the Naxal movement in West Bengal continued to be systematically decimated, by the heavy hand of the Congress government in power, under Chief Minister Siddhartha Shankar Ray. After general elections, trade unions tend to realign themselves with the political party in power in the state. Sudhangsu Ray, the union leader in the Garden Reach factory, had shifted the union’s loyalties to the Congress as well. The external trade union leaders, Laxmi Kanta Bose and Samir Roy, were also ‘Congressmen’.

Ashok S. Ganguly with West Bengal CM Jyoti Basu

After a long and drawn-out strike and endless discussions between HLL and union leader Bose, for days on end, a settlement was finally signed between the Congress union and HLL. The next day, the Garden Reach factory reopened and to everyone’s relief, the machines, once again, began to hum. My designation was deputy general manager, reporting to the general manager, Kachru. After a long strike, even after manufacturing recommenced, the work environment and the relations between workers and managers remained strained. Due to the internal trade union rivalry between the new Congress Union and the previous Communist Union, the environment within the factory remained sullen.

I continued to stay at the Grand Hotel temporarily, and formally took charge of my new role the day the factory recommenced operations after the strike. Virtually everyone in Garden Reach factory had met or interacted with me, during my ‘troubleshooting’ visit in 1971. In early 1974, Connie and Nivedita joined me in Calcutta, and after staying for a few weeks at the Grand Hotel, we moved to a company-allotted flat in Jubilee Court on Harrington Street (Shakespeare Sarani).

With wife, Connie, and daughters Nivedita and Amrita

In the aftermath of the long years of the socially and economically ruinous Naxalite violence, the overall environment in Calcutta continued to be tense. Threats of kidnapping and senseless killings were reported virtually every day. Nivedita had to be driven to her new school accompanied by a bodyguard, in the car.

Samir Roy, a leader in the Youth Congress and one of the several lumpen troublemakers, captured the leadership of the workers’ union at Garden Reach factory, from the ageing Laxmi Kanta Bose, with whom the management had signed the recent agreement. Roy and his fellow cohorts started freely moving around the factory, threatening managers and especially workers belonging to the Communist union. He not only carried a gun but was also escorted in an open jeep, by armed ‘bodyguards’, driving around the factory, without permission or consent of the management. Widespread workplace and social indiscipline were serious and threatening leftovers from the years of Naxalite violence and lawlessness in West Bengal. Indiscipline had apparently spread amongst employees, even before the long shutdown of the factory. Very soon, after the settlement between management and Laxmi Kanta Bose, and the factory reopened, Kachru was transferred to Jammu, to build the new detergent factory of HLL. Before I had time to settle, I succeeded him as the general manager.

PM Dr Manmohan Singh introducing the author to US President Barack Obama

Anil Chakravarty moved from Shyamnagar to succeed me as deputy general manager and Nirmal Sen took charge as factory manager, at Shyamnagar. The day after I took charge as the general manager, Samir Roy sent word that he wished to meet me. I sent my reply conveying that I would meet him, provided he deposited his pistol at the main gate and left his ‘bodyguards’ outside the main gate of the factory. Samir Roy flatly refused to follow the pre-conditions, at first, so I had the factory gates shut and locked. Very soon, he agreed to deposit his gun at the gate and leave his companions outside the factory. He then once again sought a one-to-one meeting with me. I sent word for him to come to my office. The news of a gun-less, cohort-less, and jeep-less Samir Roy walking to meet me in my office immediately spread all around the factory and even in the neighbouring locality. That incident turned out to be the beginning of the end of Samir Roy. I had not realized that the episode would turn out the way it did. We had a polite meeting over a cup of tea. Roy was keen to find out what sort of person I was.

With Pranab Mukherjee and Murli Deora, 1983

Our stay, at Jubilee Court, was brief but very enjoyable. Chandi Basu, the Calcutta branch manager of HLL and his wife, Rama, were our next-door neighbours. Our flats were old and spacious. I had first met Chandida in Bombay in 1962, and we had become friends. Within a few months, Chandida, as he was popularly known, was succeeded by Inder Singh. Inder and his wife, Shagufta, became our new friendly neighbours. After our brief stay in Jubilee Court, we moved to another company flat on New Road, Alipore. Our second daughter, Amrita, was born on 26 September 1974, in Calcutta. Our short stay in Calcutta, 1973–75, was eventful and enjoyable. We were saddened when it was time to move back to Bombay. Our time in Calcutta had been very exciting and happy. My apprehension of working in Calcutta was wrong.

Excerpted from Afterness: Home and Away by Ashok S. Ganguly with permission from Penguin Random House India.