He is a man of few words. He lets his guitar do the talking. Only those who choose to tune in are all ears. And only they know that today, Wednesday, October 20, is his birthday. Fittingly, he is out with a new album, announced quietly, true to character, barely 24 hours earlier. Again, those who know him know about the Roja Planta, or Red Plant, he has been nurturing in his heart for about three years from 2018. He had mentioned it to me earlier, while the idea was in gestation. That discussion about his music, life, influences and a lot more is a chapter in the book, Calling Elvis: Conversations with Some of Music’s Greatest, A Personal History.

So, here goes: My Kolkata wishes Amyt Datta a very happy birthday.

It’s nice and breezy at Swabhoomi, an East Calcutta culture hub of tasteful architecture. The Amyt Datta quartet, the fourth musical act of the evening, is playing Dance Acoustica, a sparkling guitar track that is kind of bouncy in a measured way. The bass holds it together, the percussion infuses minimalist frills while a second guitar embellishes the chords. The underlying theme pretty apparent from the early notes, Acoustica is a fantastic opening track, the kind that makes it easy for you to choose your poison for the night. Tequila with Blue Curacao, perhaps?

I have visions of a quaint open-sky café in, say, Valencia, where patrons sip Vino (wine), listen to the music and talk in hushed tones only in between tracks.

Amyt is a master of such atmospheric wonders. The kind that sets you on imagined journeys to places where only jazz can take you. Pulse, the fourth track he plays is, by contrast, busy and intricate, more demanding. Electric Insenity is bloody intense, layered as the other tunes, but aggressive. It is based on a 5-note scale devised by John Coltrane, he informs the disciplined audience by then deep into the music. Camellia is meant to soothe the nerves. It’s a slow, soulful and mysterious piece about “secrets”—very Al Di Meola with shades of Cielo e Terra.

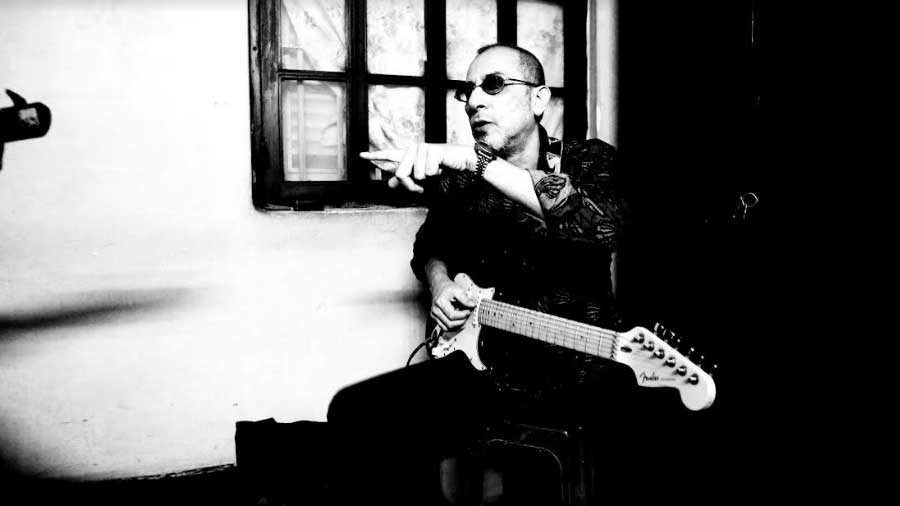

“Yes, my music is very Mediterranean-ish,” Amyt tells me two weeks later at his apartment in South Calcutta, and I remember thinking it was exactly 16 years since I heard him at Vidya Mandir playing with the likes of Lew Hilt, Nondon Bagchi and Subir Chatterjee to celebrate Dilip Balakrishnan’s music. He was Amit then and sported shoulder-length rock-star mane. Now, he is Amyt, having shed his locks for a daring close crop, a pair of shades adding to the cool quotient. His music has crossed the seven seas and beyond. Complex and sophisticated, there’s something deeply personal—as all good music is—about his guitar playing.

Jazz.

“But, it also has this undercurrent of certain Indian-isms,” he points out. “Mind you, not Indian music per se, as I know nothing of Indian music. I just use the smell of it.” To Amyt, the Indian and Mediterranean mix, however tenuous it may seem to some, is as natural as, say, the samba-jazz fusion of Bossa Nova. “A lot depends on how you are wired. Indian doesn’t have to be in the notes. It could be in the breathing, the feel. You play a flurry of notes and you slow down. There’s contrast. And I get that from watching life very closely.”

If creativity revolves around life, then Amyt is wise enough at a sprightly 56 to know that nothing comes without dedication and perseverance. “You will have to do the riyaz and the wood-shedding,” he insists, laughing while pointing out that he has been without the guitar only for the first 12 years of his life. From then on, practising has been a part of his days and nights, his mother often chiding him for not devoting enough time to the instrument.

“My mother is from the family of R.C. Boral (considered to be the father of Hindi film music). For her, music is too dear, too sacred not to pursue just because it comes with inherent career risks. I said, ‘I will try…’ One can only try. But I am very honest. If I am awake, I am with the guitar. I practise.”

Image credit: Imagine Events

Those who know him well enough say his reaction to anything and everything is the guitar. Amyt doesn’t disagree. “If I am angry, I storm into my room and pick up the guitar. If I am happy, the joy pulls me to the guitar.”

When he is not? “I listen to the everyday sounds the city offers.” And Miles Davis, Charlie “Bird” Parker and other legends of jazz. “Miles is my all-time philosopher. Just as John Coltrane is a master of his craft with the mind of a supercomputer. Consider Giant Steps.”

And McLaughlin?

“John McLaughlin is my absolute favourite. He has the romance of Spain, the complexities and sophistication of jazz and the divinity of Indian music.”

Amyt loves Laurindo Almeida too, for his “most beautiful chord voicings behind Stan Getz’s free-flowing lyricism”, Al Di Meola for bringing “Mediterranean music to the mainstream”, Jean Luc Ponty for “doing wonders with the electric violin” and of course Jimi Hendrix, Carlos Santana and Ritchie Blackmore.

Sometime in the late ’80s, Amyt and his brother Monojit ‘Kochu” Datta, an accomplished drummer and percussionist with a penchant for Latin rhythms, joined Airwave, a band fronted by Gyan Singh with his wife Jayshree on vocals. One of Airwave’s most memorable gigs was at Dalhousie Institute featuring Loiuz Banks on the keys. Hanging around with them backstage later, I remember Amyt telling us how Louiz had called the band members “masters of memory”, complementing their musicianship even though they weren’t proficient in reading notations.

“True. At the time, Mr Louiz Banks came over to Calcutta for three days, stayed at Jayshree’s house. We used to practise from 10am through the day. It was thrilling to have him in the house. That’s how we got close.”

Image credit: Proshanto Mahato

These days, Amyt is able to instantly write down tunes that come to his head, something he admits happens most often when he is on “The Throne”. He usually grabs a mobile and hums the bare-bones tune, “even though I am embarrassingly bad at it”. His approach to music is philosophical. With emotions at its core, the tunes are almost always about the “various shades of grey in between black and white”. Once ready, he loves to hold up the sheet of music and marvel at the notes, represented calligraphically by crotchets, minims and quavers, a delightful visual of the ideas that led him to the tune.

“But learning the craft of writing a tune is quite a heavy task. It’s just the notes of course. But then, I realise, it’s not the notes that we recognise as a song. Travelling from one note to the other is the key, both in terms of intervals and time and space,” he explains.

Growing up in ’70s Calcutta of divided loyalties, between the Bengali film industry and those pursuing so-called western music, Amyt’s “haateykhori (initiation)” happened courtesy Khokon Mukherjee, who used to then play with Hemanta Mukhopadhyay. Later, lessons from the late Carlton Kitto helped open a window to the world of jazz and improvisation.

Among the earliest bands Amyt remembers playing in was New Blues Connexion, a quartet that included brother Kochu. They played at Anglo Indian weddings, school competitions, fests, pubs and even small-time club gigs, loving every bit of it. Subsequently, with Gyan and Jayshree at Airwave, they did songs by Pointer Sisters, En Vogue, Nona Hendryx, Sade, Steely Dan, Doobie Brothers, Deborah Berg and many more, imbibing nuances of pop sensibilities and, in the process, acquiring a sense of discipline that comes with playing in a covers band. They practised everyday firm in the belief that the more they played more gigs would come their way.

“Jayashree would explain to me what a four-minute pop tune should contain or how to say what one has to say within a thirty second guitar solo. Taking a keyboard player’s approach would be more fitting and the fact that I had to ‘play’ to the ‘song’ was what I learnt from her,” recalls Amyt.

Image credit: Debajit Banerjee

By the mid-’80s, the siblings started playing and touring with other set-ups, primarily Shiva, another of Calcutta’s signature bands, helmed by P.C. Mukherjee. In 1988, the duo were back with Gyan and Jayshree, this time also playing originals, in various formations, most notably Pop Secret, Skinny Alley and Pinknoise.

But the good times didn’t last. A series of tragedies struck. Gyan Singh passed away, and Jayshree was diagnosed with cancer. Then suddenly, in October 2017, Kochu died. Now, Jayshree is no more. “I did not know how to look at life. With anger? Or with hopelessness? I was in a vacuum and my music became silent. Dead were my notes,” he wrote in The Telegraph.

But Amyt has soldiered on, vowing to himself to carry the torch. He has stayed on in Calcutta even though his music could have taken him anywhere he chose to go. “Luckily, for me, I don’t think too far ahead. But yes, questions do arise. Should I have gone to New York? These days, when I go there, although not as frequently as before, I realise it’s no longer what we used to think, that every American musician was better than us. Some of us have managed to go over to the other side.”

Here’s how. Amyt’s first three albums, Ambience de Danse, Pietra Dura and Amino Acid, were composed between 2008 and 2011. Now he’s working on Amygdala, which Googles to “an almond shaped part of the temporal lobe of the brain involved in emotions of fear and aggression”. Amyt describes Amygdala as a “surgical inquisition of the guitar,” for which he’ll be resorting to OTX, or octave tuning experiment. That means, he will be altering the order of the guitar strings from the conventional E, B, G, D, A, E. “There are about 20 ways one can do this, I have zeroed in on one.” But before that he wants to record an album of seven tracks, tentatively titled, Roja Planta.

Image credit: Vedic Village Spa and Resorts

The text has been excerpted from Calling Elvis: Conversations with Some of Music’s Greatest, A Personal History, published by Speaking Tiger Books, January 2020.

(Buy the book here.)