On a quiet Sunday morning in Calcutta, over a cup of Darjeeling cha with stevia, Amitav Ghosh sat down for a conversation with t2oS that steered clear of the blitzkrieg of his newest book Smoke and Ashes. Rather, he spoke about memory and language, journeys, his reverence for Sunil Gangopadhyay, writing and more. Excerpts.

Journeys have always been exceedingly important to you. The Circle of Reason has an interesting ending with a sea voyage, The Hungry Tide, The Ibis Trilogy, The Nutmeg’s Curse and, now, Smoke and Ashes are all primarily about journeys. Are these driven by an inner journey of self-discovery?

It’s really the story of my life. My father travelled a lot and my life has literally been going from one place to another. At the age of 11, I was sent away to boarding school.... So you know there are all those long journeys. I was just remembering when I was in Chennai a couple of days ago that there would be all those long journeys from Dehradun to Chennai. So those long journeys have also been so much a part of my life. Actually journeys have been a part of my life. And they actually began before I was born. My family, as you know, was displaced from Bangladesh during Partition and moved to West Bengal and Bihar. So, in a way, journeys are in my DNA.

In The Hungry Tide, some of the global citizenship issues presented by you have their roots in migration and globalisation as seen in Piya, a cetologist (studies marine mammals)...

Certainly the character of Piya is very interesting to me because scientists of that kind are very interesting because they are fighting a losing battle. In this age of biodiversity loss, it is really a very tragic predicament you know. They devote their lives to one creature — in this case the Irrawady dolphins — and then they literally watch them disappear in front of their eyes and it is devastating to them.

Your recent works — Jungle Nama, The Living Mountain, The Nutmeg’s Curse — are about ecocriticism. So, would you like to tell us a little bit about how humans are ushering in this disaster?

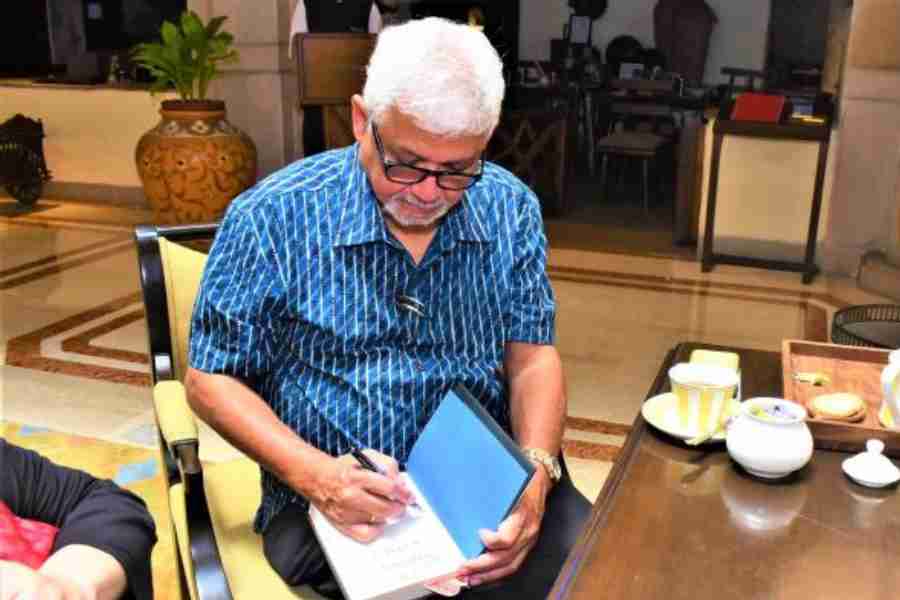

Amitav Ghosh autographing a copy of Smoke and Ashes

Smoke and Ashes was not conceived during the pandemic. It was The Nutmeg’s Curse that I wrote completely during the pandemic. I gave up Smoke and Ashes in the middle, and then I came back to it again. Absolutely right. Humans are creating this disaster in every possible domain. Whether we are talking about pathogens, biodiversity collapse, ecological disasters, humans are absolutely responsible. You know it’s not that humans are able to do all this. But that the Earth is striking back.

So the Earth is saying “enough”?

Exactly.

How do you get the cultural ethos so correct? In the context of The Glass Palace, for example, it has been quite surprising to have strangers or even friends come up and say “Oh! My aunt is in that story”.

Oh you mustn’t believe those people when they say that (laughs).

So how did you research The Glass Palace? Did you speak to a lot of people over many years?

Yes, yes. I talked to a lot of people. I read a lot of memoirs. And you know my website has become a clearing house for people who were on the long march. Yes. It’s become a real resource for those people, and I spoke to many many people. Not so much in India but more in Malaysia and Singapore. And that’s where I first met you because that is where I was researching the book, a long long time ago.

You do go to a lot of trouble to get such detailed information to capture the essence of a place. Writers who are situating their stories in Southeast Asia often look upon you as some sort of oracle!

Sunil Gangopadyay

One of the things that I feel that is happening with people who are writing non-fiction books about history is in some ways it is a response to the work I have been doing. It opens gates for them.

In the field of fiction writing, does mentorship play any role today, or is it a private enterprise?

This was certainly true for our generation. We all approached things on our own. But it has changed completely now. A lot of writers come out of creative writing programs today. They all talk of the bonds with their mentors and really, that is the function of the creative writing program. Not so much to teach but to give people networks. I think that has become the case today. That was not the case for me. I never had mentors in that sense. I had friends like Sunil Gangopadhyay — he was very important to me.

What intrigues many of your readers is your ability to produce work of consistently good quality. Would you say you are a disciplined writer? Do you prefer to write at your desk at home, or because you travel so much you write everywhere?

I do a fair amount of writing when I am travelling. And I take notes while I travel. That’s a very important part of my process. But when I am at home I work in a very regular fashion. I don’t like to call it discipline. Maybe 30 years or 40 years ago… why discipline? Because I had to make myself do it. But now it is so ingrained I just can’t stop. Some years ago I thought I would work less. In the afternoon I would just read or I would just go for a walk. But I was bored out of my mind.

Each writer works at her own pace and selects her own time in the day to write. Do you say to yourself, ‘I am going to write from 5am to noon today’, or something?

Yes, but at some point in your life you have so much else to handle, and your schedule becomes so complicated and you have to be corresponding with your publishers all over the world, so looking after the business side of things becomes a lot of work.

Time to hire a business manager?

Yes, some people do that but I can’t work like that.

What jumpstarts a project? Do you all of a sudden get an idea at night and when you wake up in the morning say yes, I will begin with this?

That happens! It’s not as if that doesn’t happen. And often when you are working, you will have ideas when you are sleeping. There’s no one way. There are many different ways how things transpire. Sometimes you have a general idea, sometimes you have a flash of inspiration where you can see it right through and see clearly where you are going.

So when you sit at your desk, what do you see outside your window?

I have a very nice view from my window. It’s quite a peaceful neighbourhood, really. In Brooklyn. Manhattan would be busier. The street is always interesting to me. Around three o’clock, kids get out of school, and they run up and down always making a racket.

In all your innumerable meetings with people, do you recall one or two who had an impact on you?

(Thinking for a few seconds and then a surprising recollection)

Yes, one person I remember very well is Khieu Samphan (now 92, is the last surviving top leader of the Khmer Rouge, whose radical policies are blamed for the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million Cambodians. He was a colleague of the infamous Pol Pot convicted of crimes against humanity in 2014 and sentenced to life imprisonment).

Did you meet him?

I met his brother when I was in Cambodia during the UNTAC elections — 1992-93. My impression of Cambodia made a tremendous impact on me. I was writing about it.

AMITAV GHOSH INTERVIEW Julie

How do you configure memory and history? Piya’s connect with the word gamchha and the universe of memory that the wash cloth of her father’s means to her. What do you think makes memory such a strong marker? And how does the instability of memory inform fiction?

Yes, memory is often unstable, And it is interesting that you mentioned the gamchha. We have the gamchha in Bengal, Assam has something very similar, Burma has something very similar, and Cambodia has something very similar too.

The krama is the Cambodian gamchha.

Yes, that’s right, the krama. Strange how garments can remind us of the past and how they can remind us of other places.

So how does language work in the arena of memory? And considering that you speak so many languages… how does language help you in your creation of stories?

Oh, there can be so many ways that language can enrich our writing. Certainly, Bangla for me can be enormously enriching. And for me Bangla has given me so many resources.

Do you find yourself thinking in English mostly?

No no. It really depends on what I am thinking about. I think in many languages.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College.