Aanchal Malhotra, the feisty new voice in the much-excavated minefield of the fiction of Partition, tells The Telegraph with audacious honesty and concision how her training as a historian has given her the tools to write a fascinating novel that straddles her own family’s history and India’s national history. Excerpts

Thirty years old, and you are one of the newest writers on the block who has forged a luminous path to creating a debut novel about Partition. Could you speak of how and when you got to be interested in pursuing the history of Partition, and how it led you to further research and studies in Montreal?

I was in my early twenties in 2013, on a sabbatical from graduate school in Montreal, when I first discovered my family’s stories of Partition. These were stories I’d never read about in my textbooks at school (that had mostly focused on the statistics and politics around Partition), the detail and depth of emotion with which they were told even decades later left me transformed. I actually felt quite ashamed for having lived so much of my life without knowing my ancestors’ histories, migrations, struggles, ways of survival, the remembering and forgetting of a home left behind, and rehabilitation in a new land. I became very aware that I belonged to a generation that did not know enough about this part of the past, but also how much the past still influenced the present. And so, I began recording stories beyond my own family, community and nationality, in the hopes that they’d remain for posterity.

Your evocative and highly nuanced novel The Book of Everlasting Things is a dream that swaddles in its folds Hayden White’s fine theory that ‘history is fiction and fiction is history’…

My way of thinking and methodology of research has never been confined to one form, and I want to think that the writing produced also defies the hard boundaries of a genre. I may have felt differently as a novelist had I begun my career writing more conventional, archival histories, but when your source is oral, situated at the axis of remembering and forgetting, it is not without its drawbacks, and I take that into consideration. The edges of my projects are always feathered, there is no obfuscation, they escape into each other. Some of the stories I recorded as an oral historian — very much rooted in reality — read like fiction, unimaginable. On the other hand, some of the scenes from my novel — constructed, imagined — feel utterly real. I am interested in the elasticity of history, both by exhuming voices that have not yet been heard, or by inserting fictional characters into it.

The compelling story of the family saga is unpackaged delicately, like we might, a tortilla — but with immense force and with the reconstruction of a lost homeland. What were the hardest hurdles to negotiate in this ride on the time machine?

A: The reconstruction of a lost homeland is something I’ve done in both Remnants of a Separation and In the Language of Remembering, but it is generally limited to the extent of a single conversation or memory with my interviewee. Together we explore notions of longing and belonging for the extent of time we spend together or the period of life that is being recounted, and it is always in bursts of memory, hardly ever linear or chronological.

But for this novel, looking back, one of the most difficult things was to follow a life from start to finish, as is the case with many of my characters. From the moment they are born to how and when they die, and the ways in which they have navigated their life amidst various social and political events of their days — war, Partition, riots, exile, desertion. Balancing these along with slow-moving everydayness, the construction of an entire life was certainly a challenge.

What are the emotional highs you experienced, for instance with your grandmother — can you explain the erosion and sadness in your bonding with her with some sad stories about leaving a homeland, Pakistan? The spark of the creation of the Museum of Material Memory with objects that triggered memory.

There are some passages I wrote in the chapter titled Memory in In the Language of Remembering, where I reflected on exactly this feeling of the erosion of one’s memory and its impression upon another’s. I am sharing them here.

“. . . each time I speak with my grandmother about the days of Partition, I descend deeper into her memory. I begin to know her as a teenager, understand more about how she would have felt, what she would have lost and what she would have gained. I remain struck, though, by how every time we speak on this subject, there is always something new added, something more, something deeper that has been retrieved. And I think to myself, how can there always be more? Is the inherent nature of memory to be cavernous? It is never chronological, often sporadic, a latticework of images, requiring gentle nudges and cues for remembrance, but always offers more. . .

“I have often considered whether her memories of Partition have somehow transferred to me. Whether, through the tenor of her voice or the frailty of her touch, through the details she provides and the silences she recedes into, I can feel part of what she feels. Obviously, I cannot feel with the same acuteness or accuracy, but some form of transference has allowed this memory to be shared and perceived deeply across generations.”

Aanchal with her grandmother

Your family story is an intersection of personal and national history — much of our history of decolonised nations is an admixture of several histories. Can you explain this?

I think this is the case for most families in the subcontinent, particularly viewed through the prism of the year 1947 and events that surround it, and this is exactly what I had wanted to document when I began writing on the subject. For so long, the history of decolonisation, Independence and Partition had been told through politics and politicians, or a story of India versus Pakistan, or the Congress versus the League. The lives of common people — their trauma, survival, rehabilitation, all as a consequence of unprecedented circumstances — hardly ever found place in the narrative.

When I began speaking to survivors on both sides of the border, the most common reaction was, “Well, what can we tell you about that time? We were not politicians, we don’t have anything important to tell. We didn’t know what was happening. One day we were there, and the other day, we had to come here.” The feeling is migration and refugeeing had become so normalised in their minds, particularly for people like my grandparents who lived in camps along with thousands of others who had experienced similar tragedies, that their main mechanism of survival became looking forward, trying to rebuild

their lives, insofar as was possible.

I remember an interview where a woman told me that the reason why she was able to survive the consequences of Partition — despite being a young girl at the time — was because her parents never dwelled on it. They never lamented on the loss of home or land; instead, they taught her and her sisters to look forward. “And so, we learned to take Partition in our stride as something normal,” she said to me, “…which it wasn’t.”

This is just one example, but I often noticed how this pivotal moment that stood at the intersection of personal and national history — was buried within, either for lack of wanting to revisit that which cannot be retrieved, or not knowing how to speak about it, or not being asked about it. Sometimes these moments need intervention, the involvement of another generation — a child or a grandchild — for an aged trauma to reveal itself.

I write about this extensively in In the Language of Remembering, but even in The Book of Everlasting Things, it is only through conversations with their respective grandchildren do my main characters, Samir Vij and Firdaus Khan, who have both lived through Partition, begin to reflect on how their “youth was unkind [to them], that it happened at a time when it could be easily seized and swallowed by the violent ongoings of the world”.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College.

The Canadian experience and your grad school, how did that shape you as a writer?

It shaped me entirely, in fact. Despite growing up in a family bookshop, I never had any intentions of writing seriously. My main way of artistic expression was the creation of images. I don’t think I’d have begun writing if I didn’t have professors in graduate school who showed me — through their own practice — how artists can also be writers, and how visual writing can be.

You are a very young writer with success and a path you have forged. What is your next story going to be?

Thank you, that’s so kind of you. I do want to say though that sometimes early success is a terrible teacher, and it has led me to hold a very high standard for my own work. As of now, I have ideas for both fiction and non-fiction, and am slowly working on giving them shape. But I’m also just enjoying the process of reading for pleasure.

In a transient world that is so unsteady and impermanent, is there really a way to think of everlasting things?

So true, but there are some aspects I’ve discovered in almost every conversation I’ve had, no matter where we come from in the world — the feelings of loss (in the entire spectrum of the word), the hugely adaptable nature of the human condition, the curiosity for our own history, and the desire to be loved. These are everlasting.

Pictures courtesy Aanchal Malhotra

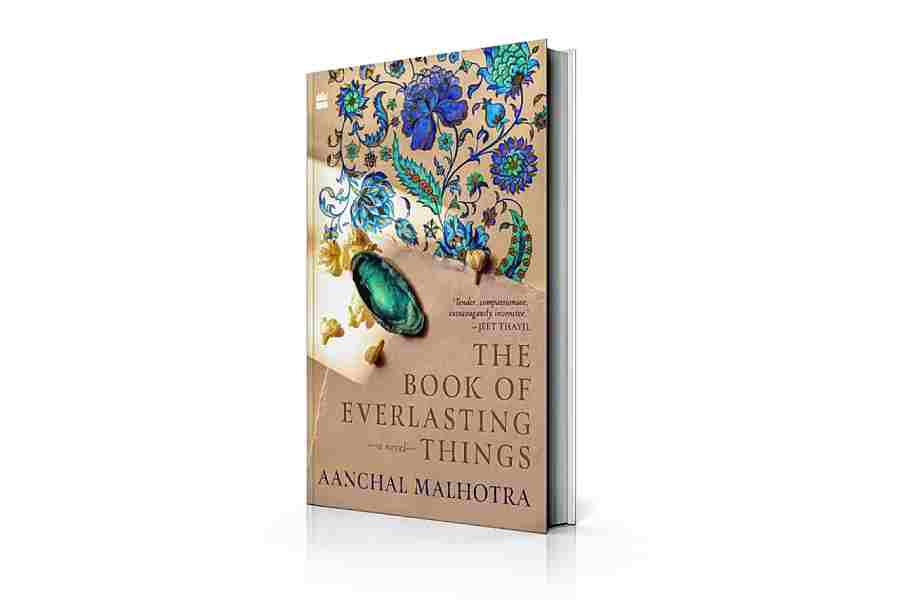

THE BOOK OF EVERLASTING THINGS

Written with unabashed passion, in elegant, compelling poetic prose, The Book of Everlasting Things is as much a tribute to those in the writer Aanchal Malhotra’s family who fought the good fight to survive, and an introduction to the national history of Hindus and Muslims who sacrificed unbidden during the Partition of the sub-continent.

Aanchal Malhotra is a quiet achiever who is tireless in her efforts about excavating personal stories from those like her grandparents who silently worked from refugee camps, towards building a life and leaving a legacy for the next generations. After a transformative conversation with her maternal grandmother, she was driven by an inner urgency to resurrect the lives of her ancestors who had worked ceaselessly to build a new life post-Partition, when they became refugees, outcasts from their own home — Lahore, Quetta or Rawalpindi. She is a historian by training and is a specialist of oral history. She is the cofounder of the Museum of Material Memory, and has written two non-fiction books on the human history and generational impact of the 1947 Partition, titled Remnants of Partition and In the Language of Remembering. In the invocation to The Book of Everlasting Things, the 30-year-young debut novelist Aanchal Malhotra invites Memory as the perfect guest to her party. Selected to set the trajectory, in a thoughtful and thought-provoking tale of Partition, Malhotra installs powerful thoughts by Joan Didion to show how a place can travel with people who are migrants, refugees or just travellers, because they are at the core of the creative imagination that Salman Rushdie so aptly terms “imaginary homelands”.

A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his own image. — Joan Didion, The White Album, 1967.

I caught up with Aanchal Malhotra at her home in Delhi, sitting at her writing desk by the window. Outside, she notices, the lemon tree is in bloom and “I can see its branches casting beautiful shadows on the house across the lane. The sun is a shimmering gold, despite the tempestuous weather we had yesterday. I have two notebooks open on the desk, a pile of books — read and unread — and I am just going to begin my weekly ritual of filling my fountain pens with ink”. The attentiveness to detail and the keen sense of place is a happy marriage of historian and storyteller.

This novel is a family saga encompassing the planet’s embattled places, linking past and present. Located in the seismic event of the Partition of the Indian sub-continent, this is a story that reveals the history of two people — Samir and Firdaus. Samir is a Hindu who becomes Indian at Partition and Firdaus, a Muslim who becomes a Pakistani. Wrenched asunder between what they want and what they must do by the binds of duty, sutured together by forces of family and fate, they need to figure out what memories they must hang on to and what memories they must bury forever.

Historical memory has often been used as a strategic tool to recover and reconstruct history, for instance in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, where the imperial oppression of America in central American countries like Colombia has been explicated, Michael Ondaatje’s novels such as Running in the Family and Anil/s Ghost, Judy Fong Bates’s memoir The Year of Finding Memory, Joy Kogawa’s celebrated novel Obasan, as well as Turkish novelist Elif Shafak’s Ten minutes and 38 seconds, is often the “Global Positioning System” (GPS) to interlace personal history with cultural or national history.

Aanchal’s grandparents, who met in Kingsway Camp, Delhi

Where the newness enters her project is her introduction of the sense of smell, which becomes a tool for the protagonist to resurrect the entire ethos of a space, a community and a person. The idea of synesthetic imagery, using the senses to process how we remember, becomes a central means to precisely recall. Here, the nose becomes the trope for memory recall. How did this idea come to Malhotra?

As one of the protagonists in The Book of Everlasting Things says, “Of all our senses, smell is the most fragile. It is the least understood, and also most secretive.” Says the author: “It has an extraordinary power to exhume memory, transport us to different places, and even keep us connected to those no longer around. But if you think about it, my earlier historical workwith migratory objects of Partition also did that — textiles, books, utensils, keys, locks, photographs, all became catalysts to reach into the past.” When she began writing this novel, though, it was with mere curiosity about smell. “Some years ago, my mother had told me a story about the time her father worked as a chemist at a pharmaceutical company and dabbled in amateur perfumery. The amorous, visceral manner in which she narrated those memories stayed with me, and helped to build the character of Vivek, one of the main perfumers in the book.”

Growing up in Delhi, Malhotra says she knew that her grandparents owned a bookshop in what was known as a “refugee market” but she says she never quite understood that they had been refugees because of Partition. “If they ever told stories of their childhood, it was always of the fruit orchards in their village or how long it took them to walk to school — the mundane, everydayness of life — but stories of violence or trauma were never discussed.” The almost bold and resolute approach to silence the terror, oppression and poverty that comes with a state waging war against a people who are unwanted and are made stateless, lies buried in the blotched history of many nations. Canada, mostly revered for its unhindered fairness as a multicultural nation, has an irredeemable history of oppression of its own Japanese-Canadian citizens during the Second World War, when the Japanese-Canadians were corraled and kept in subhuman conditions. Malhotra, who did her graduate studies at Concordi University Montreal, would be aware of the way the Japanese Canadians, citizens of Canada, were ostracized in the last three years of the Second World War and the way they were dispossessed of their belongings and their homes. The pain and suffering borne silently resonated with the stories of Partition refugees in the subcontinent.

There was something liberating about the genre of fiction — ”I could construct and reconstruct the stories of my characters, whereas in non-fiction, I could only transcribe and interpret them, never alter the testimony I was receiving,” admits Malhotra.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College.