That’s the last thing anybody would have wanted. Take him on that day. The ‘King’, you see, was in the mood and didn’t give a damn.

Rewind then to that summer, if you will. Jeff Thomson is into his run, the speedster’s rhythmic canter before the javelin throw of release. True, he was not quite the old Thomson of incandescent pace, but he was still quick. And psychologically as lethal.

At the other end waits this man, narrow of waist, broad at the shoulder; gum-chewing irreverence under maroon cap. He never wore a helmet; for a change, peril lay not in the person charging in.

The ball whizzes towards leg. The man in the cap makes room as bat explodes in brutal arc. Six! Over extra cover. Not too often in his career had Thomson been treated so. But not for nothing did they call this man the King. It was Lord’s, June 18, World Cup 1983, that glorious summer of the underdog, but we’ll mention that in passing. This is about Vivian Richards, also known as Sir Viv.

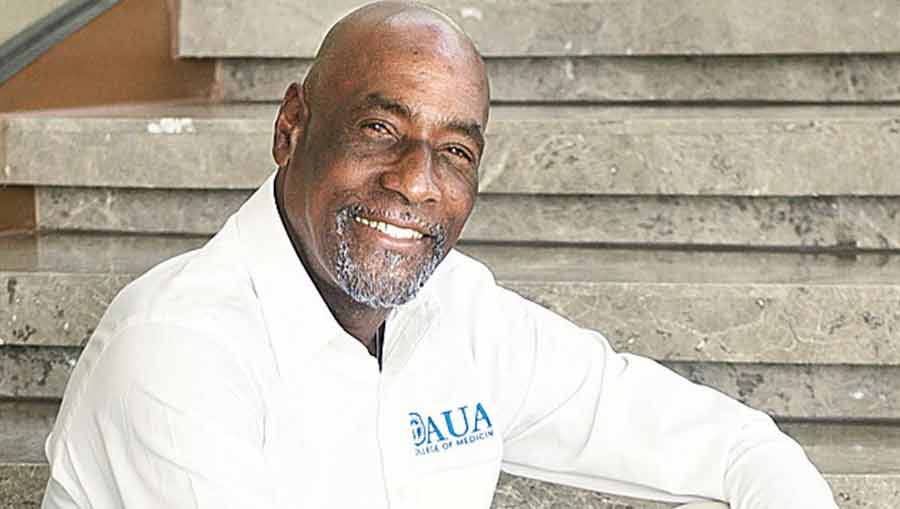

Richards racked up over 8,500 Test runs, at an average of 50-plus for every saunter to the crease TT archives

He was 31 then, in his prime, and possessor of an aura as fabled as the legend himself. Fast forward to March 7 this year; that’s the day he turns 70. Sixty is officially elder but there’s something reassuringly sage about a septuagenarian, just as yesterdays are a consolation against the ambiguities of tomorrow. A tribute is in order, surely? Not that Sir Viv requires any; his place is assured among the pantheon of all-time greats, so let’s put this in another way. This is a tribute to the allegory called Richards and the idea he inherited. Of cricket as a search for identity and the heady exuberance that accompanied that search. Subjugated for long, brutalised by slave-owners and denied a birthright to history, the Caribbean yearning for freedom and fulfilment had burst out in their play, the pitch their passport to deliverance.

Few have exuded such an air of dominance at the crease Tweeted by @windiescricket

Cricket was their protest and transcendence, “born (and) raised… within the fiery cauldron of colonial oppression”. That was historian Hilary Beckles on the development of the game in the islands.

Richards embodied that transcendence, in his lordly nonchalance, his deliberate saunter to the crease and in his helmet-less destruction of bowlers, even the quickest of the lot. He was the “black man asserting himself in this world”, he would write in his autobiography, Hitting Across The Line.

It would be the triumphant high point of what C.L.R. James said in Beyond a Boundary: “On the cricket field, all men, whatever their colour or status, were theoretically equal.”

An unequal field

For long, though, the field was hardly equal, not even in theory, save for the rare occasion when white plantation owners would let their tall, robust slaves drop their manacles so that the masters got some batting practice. Bowl as fast as possible, was the command. And bowl fast they did, the throw of the ball their symbolic catharsis. It’s an imaginative reconstruction, stunningly visual, from the pages of author-historian Tom Holland’s essay for Wisden — Cricket and Slavery — and surely the rudimentary beginnings of West Indian cricket.

He was the ‘black man asserting himself in this world’, Richards would write in his autobiography, ‘Hitting Across The Line’. Tweeted by @icc

That would have been centuries ago. By the time the game took a break for the Second World War, West Indian cricket had got under way, genes and circumstances shaping what would be an irrepressible syntax — a game as free-flowing as the music of protest. If runs bubbled from ‘Black Bradman’ George Headley’s unhurried blade, Learie Constantine and Manny Martindale reenacted the early unshackled swing of the arm that had once offered fleeting respite from bondage.

Cricket was their emancipation; they just needed to toss away the psychological tether of thraldom, as Bob Marley would sing later in his Redemption Song.

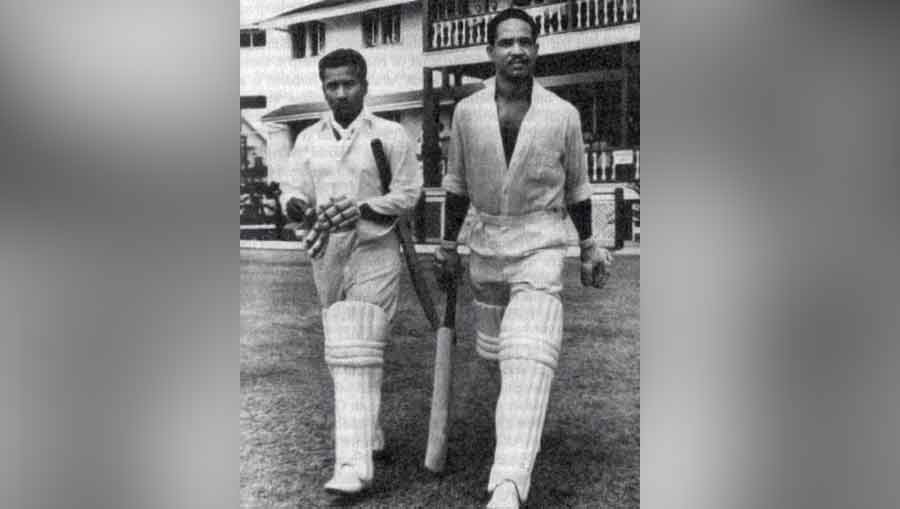

After the war would come men like Frank Worrell, Clyde Walcott, Everton Weekes, Rohan Kanhai and Garfield Sobers, to name some of the greatest ever to hold a bat, all immortals of the game, who played like inhibition-less gods and made devotees of generations. So enchanted were the Australians by Worrell’s Calypso warriors of 1960-61, after years of dull, anodyne cricket, that thousands had lined the streets of Melbourne to give the visitors an unforgettable sendoff.

Rohan Kanhai and Garfield Sobers @John Sheppard/Pinterest

A stray image surges back, of an old gentleman, a veteran of the galleries. Sometime early in the Eighties it was, at Eden, where the midwinter sun sprawls on the grass and breeze from the river rustles on your skin like memory.

How good was Sobers, someone had asked the gentleman. “How good was he?” he had queried back, a trifle annoyed. “I haven’t watched Bradman bat, but Sobers was the finest I have seen.”

A demonstration of how fine had come a decade earlier, in faraway Australia. January 1972. Sobers, then captain of a World XI side, had blazed to 254, boundary after boundary cannoning off his bat, unsparing even of Dennis Lillee’s scorching thunderbolts. It was carnage, mayhem at Melbourne, if you prefer. The greatest exhibition of batting seen in Australia, was The Don’s unequivocal verdict. “I have seen nothing equal to it in this country.”

Eleven years later, it would be against the Australians again that Richards would explode on the field of play. His unbeaten 95 that day at Lord’s in June 1983 included nine fours and three that went over the rope, including the monstrous one he struck off Thomson.

Swagger, defiance and dominance

He made his Test debut in November 1974. By the time he rested his bat, Richards had racked up over 8,500 runs, @ 50-plus for every saunter to the crease, including two dozen centuries, with a personal best of 291.

His ODI figures were no less; 6,721 runs @ 47, at a strike rate of 90, 11 hundreds. Long before T20, the cash-rich postmodernist version of the game, there was Richards the original destroyer.

Richards' ODI figures? 6,721 runs @ 47, at a strike rate of 90, 11 hundreds Tweeted by @icc

It was how he made the runs that set him apart. The retort, so to speak, to whatever you hurled at him. Like the one that ricocheted off his bat at Old Trafford on May 31, 1984. Picture this. Ian Botham to Richards. Front foot across, whipped through the leg. Four! Botham smiles. This was going to be one of those days.

Neil Foster to Richards. Speared in towards leg. Richards steps outside leg. Thwack! Over long-off. From imperious off-to-middle swivel of wrists to cavalier inside-out insouciance. To hell with orthodoxy.

Twenty-one boundaries and five sixes had come off Richards’s blade that day as he plundered 93 in a last-wicket stand of 106. He remained not out on 189. His teammates — and extras — together contributed the remaining 83 in a score of 272/9.

Two years later, in April 1986, it would be England again that would submit to the King’s implacable blade, this time in a Test match on his home ground, St John’s, Antigua. Richards’s unbeaten 56-ball hundred — the fastest then — capped off an agonising 0-5 humiliation for the visitors. “The extraordinary, and forever memorable, feature of his innings was the way he walked off at the end,” journalist Scyld Berry would write. “It was Caesar returning to Rome after his greatest triumph.”

For those who don’t remember the King in action, Viv would keep you waiting (a vivid portrayal comes in Richards’s ESPNcricinfo profile). He would then emerge from the shadows of the pavilion into the sunlight, and then amble towards the crease. Why rush? The next few acts would be his. Seldom had the cricket field seen such swagger; his gum-chewing disdain a benchmark for defiance. If the Eighties were still a throwback to tradition, Richards was the brooding precursor of millennial cool.

Sometimes such contempt would end in disaster, as it did that summer in Lord’s against India. World Cup final, 1983. Madan Lal, medium quick but lion-hearted, leaps high, the deepening gloom of his countrymen on his shoulders.

Viv, 33 off 27 balls, ominous of intent, brazen of manner, looks to step out, then changes his mind, but doesn’t get hold of the pull shot. Hubris and instant karma. Tragedy for the West Indies, cricketing consummation for India.

In a way it was necessary human fallibility and, from a cricketing point of view, a counterbalance to invulnerability. Few have exuded such air of dominance, his very presence at the crease a foreboding of ruin.

Black pride on rasping blade

Old imperial master, England, had got the first taste of that in the summer of 1976, the King’s high noon that yielded 829 runs in four Tests, a century and two double hundreds, including his career-best 291. It was fitting riposte to Tony Greig’s pre-series bluster.

Greig had promised to make the West Indies grovel; not the most judicious choice of word given the deep racial animosities and the England captain’s white South African roots. What followed was terrifying retribution. The West Indies won the five-match Test series 3-0.

They had won the World Cup the previous year, in 1975, but had then crumpled to a 1-5 humiliation in Australia, mauled into submission by Thomson and Lillee. Clive Lloyd and Co. had arrived in England, their tactical shift to an artillery based on pace validated by a 2-1 series victory at home over India in between. Lloyd unleashed Andy Roberts, Michael Holding and Wayne Daniel on the English, while Richards, Gordon Greenidge and Roy Fredericks put runs on the board. It would be the start of their journey towards world domination.

Remember what someone had said many years ago? No army can stop an idea whose time has come, or something to that effect. In England that summer, the West Indies were that idea, irrepressibly romantic, fascinatingly lethal. Richards was its supreme embodiment.

Much has changed since. That era of unchallenged supremacy has long gone. Gone too is the enthralling alchemy of Caribbean pride and flair, now lost in the labyrinth of endless failure and ephemeral success. But there’s solace in memories, of breathtaking dominance and the imperious scorn of a man who wore his black pride on his rasping blade. History had been unkind to his people, so he set things right on the field of play, however mighty the adversary may have been. The King, you see, never gave a damn.

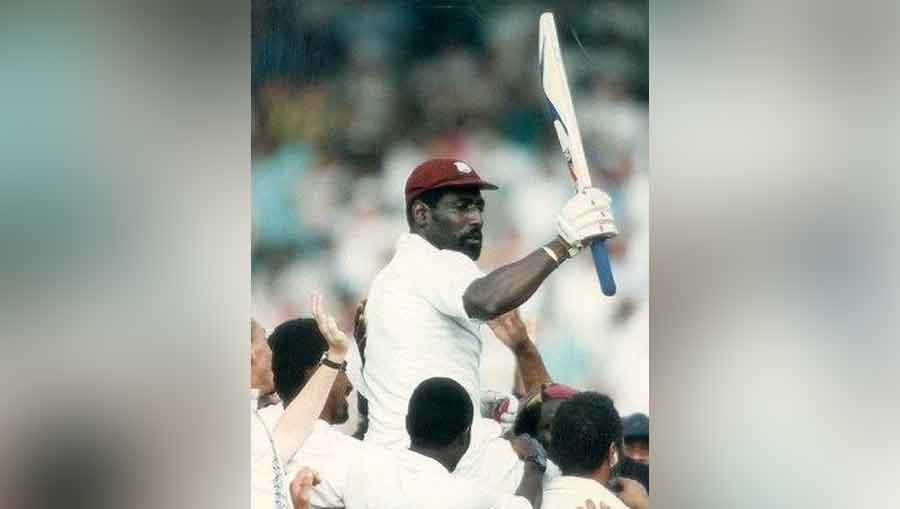

Richards is carried by his teammates after his final game Tweeted by @ivivianrichards