It was November 26, 1933. A crowd filled Howrah Station. Among the masses thronging the place were members of the royal family of Pakur (in present-day Jharkhand). The younger heir Amarendra Chandra Pandey, his sister Banabala, along with some friends and staff were scheduled to travel to their ancestral property. They were quite surprised then to spot Amarendra’s older half-brother Benoyendra Chandra Pandey at the station. The older Pandey was disliked by his close relatives. Benoyendra, like many scions of moneyed families of the time, had fallen prey to all sorts of vices. He was known to splurge money at dance houses, race courses, betting addas and had also struck up a relationship with a ‘nautch’ girl.

Four years ago, their father had passed away leaving the two brothers as joint heirs. Amarendra was 16 at the time, so it was two years before he could have a legal claim. But after turning 18 (in 1931), Amarendra started to gradually exercise his rights. This did not sit well with Benoyendra and several strongly worded letters were exchanged between the two sides.

A nefarious plot

Most of the traveling party didn’t want anything to do with Benoyendra. But Amarendra dissuaded them and welcomed his half-brother warmly. As they were about to board the train, a short man with his face wrapped in a shawl brushed by younger Pandey, who felt a sharp prick on his arm. After being seated, he rolled up his sleeve and saw there was a tiny hole on his skin which was secreting a colour-less liquid, a few drops of which had also stained his shirt wrist. Banabala, in particular, was very concerned by this incident. She kept insisting that they cancel the journey and immediately get medical help. But Benoyendra tried to deflect the situation, saying it's nothing and if at all, a doctor could take a look when they reach Pakur. Amarendra agreed with his elder brother and decided to proceed with their plan.

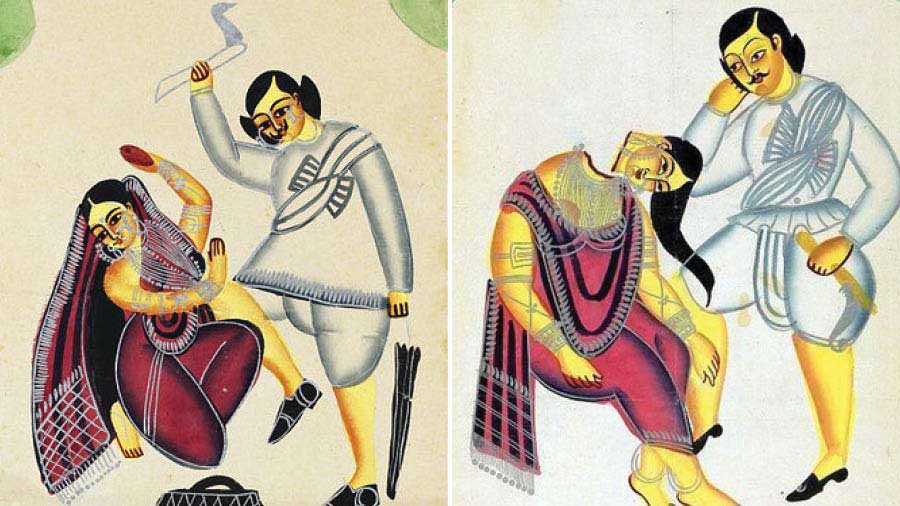

Amarendra Pandey had felt a sharp prick on his arm – he rolled up his sleeve and saw there was a tiny hole on his skin which was secreting a colour-less liquid Wikimedia Commons

Shortly after reaching Pakur, things unfolded quickly. Amarendra became seriously ill and the family rushed back to Calcutta. Amarendra's temperature shot up to 105 degrees, his right arm was swollen and his blood pressure and heartbeat were both fluctuating dangerously. A team of doctors tried desperately to revive Amarendra, but in vain. On December 3, the unfortunate young man slipped into a coma and died the next day. Banabala was distraught by grief. Both her and Rani Surjabati, the boy’s aunt suspected Benoyendra of foul play. Benoyendra had performed the last rites of his brother and appeared grief stricken. But a year ago, when Amarendra was with Rani Surjabati in Deoghar, Benoyendra had made his brother wear a pair of pince-nez forcibly, after which the young man had developed tetanus. His aunt had suspected back then that the pince-nez was poisoned with tetanus bacilli.

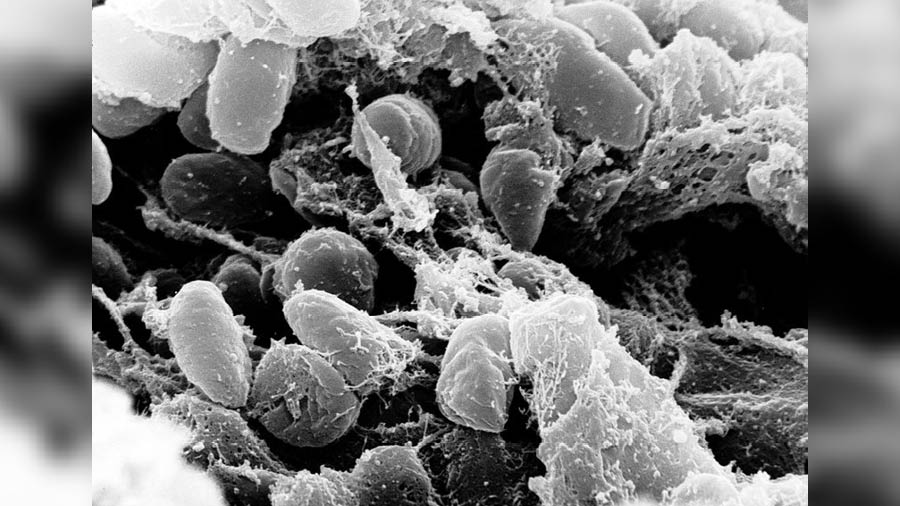

Meanwhile, the doctors treating Amarendra were confounded. How did a young healthy man of 20, with habit of regular exercising and sports, die suddenly like this. One of the doctors had sent a sample of Amarendra’s blood to the School of Tropical Medicine for culturing. When the report revealed presence of bi-polar rods of the deadly bacillus pestis (bubonic plague), the worst fears of Amarendra’s close ones seem to come true.

The plague bacteria under a microscope Wikimedia Commons

A FIR was filed against Benoyendra. The case was handed to E.H. le Broq, officer-in-charge of the detective department at Lalbazar. As soon as he’d heard of the FIR, Benoyendra had escaped, but was apprehended from Asansol station on February 16, 1934. Over the next two days, police arrested two of his associates: Dr Durga Ratan Dhar and Dr Taranath Bhattacharya. Another associate, Dr Shibopada Bhattacharya, evaded arrest for a while, but was eventually nabbed on March 24.

Officer le Broq’s detailed investigation revealed a deadly trail of malice and cruelty. Determined to deny his younger brother his rightful share of the ancestral wealth, Benoyendra had struck up a friendship with Taranath, an unscrupulous man who wasn’t even a real doctor but a lab assistant in a laboratory on Cornwallis Street. His work had made him somewhat of an authority on microbes and their role in causing diseases. Together, they'd hatched the plan to murder Amarendra using the tetanus-tainted pince-nez, but when it failed, instead of giving up, Benoyendra became even more determined.

Benoyendra and Taranath hatched the plan to murder Amarendra using a tetanus-tainted pince-nez Wikimedia Commons

Taranath tried to procure a sample of bacillus pestis from the Haffkine Institute in Arthur Road, Bombay, citing research needs. But his request was denied. Against bribe money, Dr Shibopada wrote a recommendation for Taranath as a researcher to get him access, but even that didn't work. Benoy then travelled to Bombay with Taranath, where he befriended two researchers of the Haffkine Institute. The two men were treated to a lovely evening at a posh hotel and this was how a vial of the deadly microbe came into Benoyendra’s possession. Taranath, meanwhile, had taken up work as a lab assistant in a private lab under an alias. With the vial procured, he experimented with it on rats to fine tune their strategy. After five days of research, he just vanished.

‘Rarest of rare’ in the annals of crime

It was thanks to the brilliant and meticulous work of le Broq and his team that the heinous crime of Benoyendra and Taranath came to light. After a trial that lasted for nine months, both men were convicted and sentenced to the gallows. Shibopada and Dhar got away, as there was no direct evidence linking them to the foul affair. The assailant who had carried out the crime was however never found. On appeal, the death punishments were reduced to life sentences. The heinous Benoyendra and his accomplice Taranath lived out the rest of their lives in Cellular Jail in Andaman. While delivering the judgment, the presiding judge had noted that the crime was “rarest of rare” in the annals of crime, not just in India but anywhere.

The Pakur murder case, as the affair came to be known, caused much uproar in Calcutta society of the time. Years later, author Nihar Ranjan Gupta would use the affairs of this sensational crime in one of the novels involving his private detective Kiriti Roy. The Pakur murder case would certainly prove true Jatayu’s famous claim: “Truth is stronger (stranger) than fiction!!”