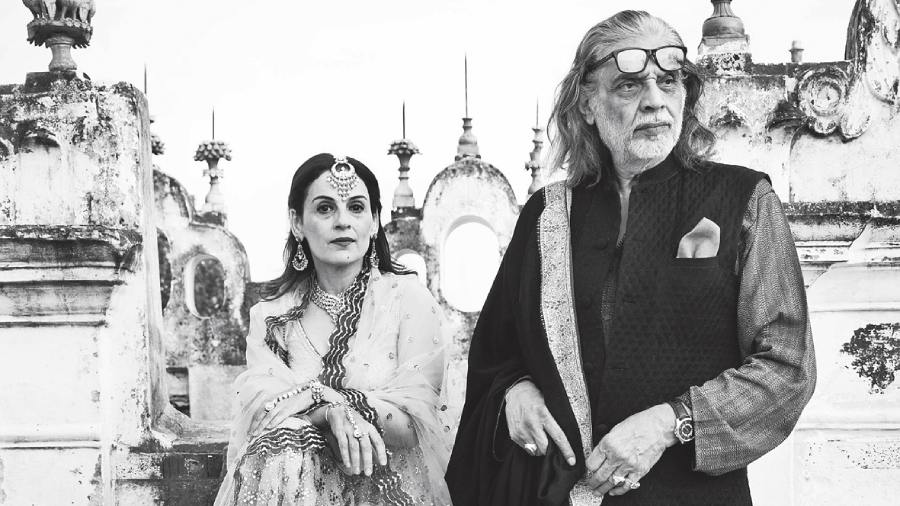

One of them an architect by profession and the other a film-maker, their shared passion for fashion gave birth to the over-three-decades-old fashion label House of Kotwara, a labour of love of two creative minds with a penchant for a heightened sense of aesthetics, too.

Way ahead of its time yet rooted in tradition, the label pays homage to the local crafts of Awadh and blends in contemporary choice in fashion and style with every step it takes, without compromising on the traditional touch. The fashion house that played a vital role in reviving local crafts of Lucknow and Kotwara, shaping the lives of the craftspeople of Kotwara and championing owning heirloom, sustainable clothes right from the start of its journey, was a serendipitous venture of these two people. During their recent visit to Kolkata with their mixed media production Weaver of Dreams, The Telegraph caught up with the House of Kotwara founders Muzaffar and Meera Ali for a tete-a-tete on fashion, films, Kolkata and more. Excerpts:

Muzaffar, you have a long association with Kolkata, how does it feel to come back now and how do you perceive the city now?

Muzaffar Ali: Kolkata has various layers and shades. Some layers have changed and some layers remain. I hope that the layers that are there from before should be properly preserved and protected. A lot of architecture, poetry, music — all these old-world charms of Kolkata, and also the cinema of Kolkata that I knew, was different. Today the cinema of Bengal is a little different. Somewhere we have to create a living relationship to the past. It is there but it is a little challenged and threatened. But a lot of good things are there also because a lot of young and modern people have come up as custodians of Kolkata, which should be of help. However, a certain amount of aesthetics has to be included into the modernity of Kolkata. Somewhere there is a lack of that. Because that is what Kolkata was. A lot of care went into designing and we need to put the same care into the future of Kolkata.

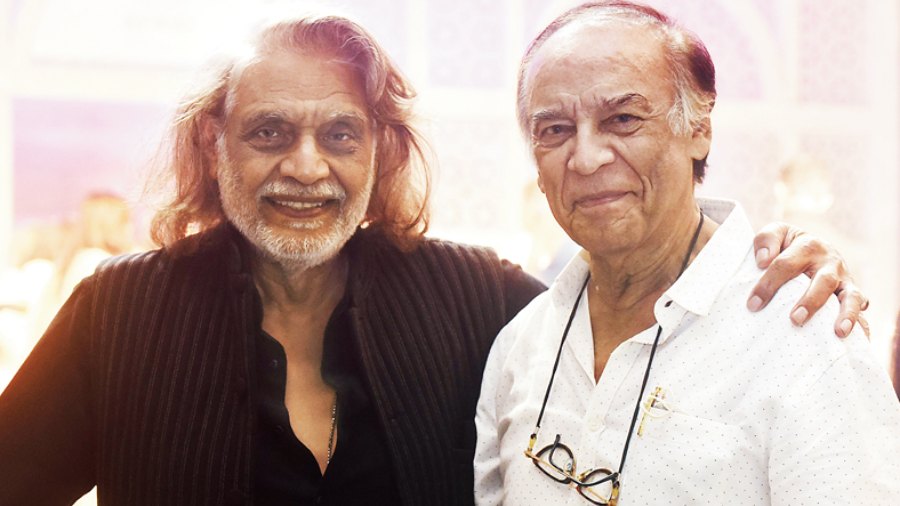

What do you look forward to most when you visit the city?

Muzaffar: Oh! I love to meet people. People of Kolkata are very warm. They are very stimulating and inspiring. I have got some old friends and every time I come, I love to make new friends. But I wish to do certain things with this place, which will create a longer-lasting impact. Maybe a film and a film that would be dedicated to the Ray school of thought.

How has Satyajit Ray inspired your film-making journey? You had worked with him too…

Muzaffar: One way it inspired is it made me realise how important film is for a culture. And which is particularly the kind of culture we come from. That is what I did in Umrao Jaan. I made culture a kind of statement. Something that a Ray could have thought of. But I did it in my own way with music and poetry... but still Ray needs to be celebrated more than ever now.

Kolkata is known for its food too…

Meera Ali: We ate kochuri yesterday and even for lunch I had this fantastic fish with one single bone, cooked in a mustard curry. I am taking back different kinds of sandesh and kasundi. And the gondhoraj lemon served with our food was also fantastic…

Muzaffar: I love all kinds of food here right from home-cooked food to street food.

Meera being an architect had the gift of drawing and sketching. Meera sent Sama to London to study fashion and she brought a new kind of sensitivity. It is a difficult journey dealing with craftsmen, people, markets, temperament. I think she puts a lot of detail in what can be done. The kind of nuances she puts in embroidery, I feel really proud to see the kind of sensitivity she has. I think it is very easy for people to loose that sensitivity — Muzaffar at Weaver of Dreams

Meera, apart from being a fashion designer and architect, you are an author too and wrote the book Dining with the Nawabs…

Meera: We have a little dining experience in our studio in Delhi, too.

You are a woman of many passions. Which of these define you and your passion the best?

Meera: I think my passion is really architecture and it draws me. And now that Sama (daughter) has joined, I would like to give more time to that.

Muzaffar, your two passions — fashion and films — often intertwine with each other. What helps you to express yourself better?

Muzaffar: Obviously films because they have emotions, story, milieu.

Weaver of Dreams is a mixed media production. What is the genesis of this production?

Muzaffar: My passion is craft and through craft you can weave dreams. You just don’t dream for yourself, you dream with and for people who are working with their hands. That is the genesis of this production and it is not a static thing. It is a dynamic thing that is evolving. I am not being able to do a lot with Bengal’s craft, the jamdani weave here. Maybe someday I would like to blend craft, the craft of Awadh and the craft of Bengal because both these cultures have a commonality.

Did your visual arts background help in blending diverse art and crafts in your work throughout?

Muzaffar: Visual art is a multidimensional thing. Including photography, videos... specially when it comes to films we are seeing art as an expression of a culture. Then we go into those details to make it look as real and authentic as it can be. It becomes very different because the whole discipline of presenting a film takes us into a time and a place. That defines the look and feel of what we are showing. Even my sketches emerge from the same concern and same inspiration.

How did it take a turn into fashion?

Muzaffar: It is a two-pronged thing. One is to connect with users and the other is to empower the craftsmen. To empower the craftsmen was my primary motive. After that this whole thing of connecting with people, inspiring them and making them feel good came into being. I got into it through Umrao Jaan and I was hands-on into it myself because I just knew what I wanted. When I was making Zooni in Kashmir, I had the American designer Mary McFadden work with me. So, it came two ways. One is through the professional and next through my personal passion and association with clothes.

Meera, designing must have been a part and parcel of your life. But how did that take a turn into fashion and has your training in architecture in any way influenced your profession as a fashion designer?

Meera: With architecture what happens is it hones your skill as a designer. So it gives a lot of awareness on what design is, what influences can be like. Design is something that can move laterally, right, left and vertically up and down. There are many architects who then later become interior designers or even enter other fields of design where they can express themselves. That kind of education helped me move towards this and as an younger person also, I was very close to wanting to do fashion.

But it never struck me until I moved to Kotwara after we got married. That is when I realised I could use my skills in other fields also and it turned out to be this. Then there was Muzaffar’s passion for clothes and understanding of clothes because of cinema and how clothes are used in cinema. If one comes from that background, then it is very important that they see clothes very differently. They see them in movement, in colour and how light and shade falls in it. How does mood vary when someone wears it. So a lot of changes happen in fashion. That was my beginning.

Your palace in Kotwara is considered to be a museum. How much have you helped in the interiors?

Meera: I have finished conservation of a 1850s building, which is our home in Lucknow. I have started restoring our palace in Kotwara, which started building in 2007 and then in phases. And our studio in Delhi is also entirely designed by me.

What are your earliest memories of taking any interest in designing or fashion?

Muzaffar: Whatever I saw my mother do, whatever I did in Umrao Jaan all these things are important milestones in this area. Even Gaman took me into the need for women empowerment in this area. In a way, they are all interwoven and connected.

Meera: I was good in sketching in school. Art wasn’t my subject but sketching was a little magical but my interest in sketching was more human form. But I never took it seriously really until I went for architecture and my sketching skills were required.

How has Lucknow or the Awadhi culture inspired your fashion journey?

Muzaffar: Lucknow is a city of craft. It is a city of style and finesse. Lucknow inspired all my films, be it films that showed fashion or films that didn’t. Lucknow to me is an integral location and culture to my craft.

Meera: I would say enormously because first of all we started working with the embroidery of chikan. Seeing old pieces of chikan, seeing them in the house in Muzaffar’s family and then film costumes, all of these had a very strong impact because we developed a sense of classicism in Awadhi couture and how to move forward taking that classic and traditional form and how to contemporise it. It started from a very traditional, very elaborate, very difficult to wear gararas that were over the top and moved to a more contemporary style. So all of these that I saw in Lucknow, in Kotwara, in the family, all of that was the foundation for me. When we moved to Kotwara we realised what do we do here. Fortunately, I had a manager who knew how to do embroidery and taught the girls and that grew and evolved into the label.

Over three decades in fashion. How has the label blended in with time and what helped it to stay relevant over the years?

Muzaffar: I think, basically the sensitivity of the audience, the wearer or the clients . They are very sensitive to what we are trying to do and our own efforts in trying to reinvent things because unless you try to reinvent craft, the craft dies. That way Kotwara is a good experiment for this purpose.

Meera: There are two types of fashion. One is high-street fashion, fast fashion and the other is what we do in couture. Our focus is slow fashion. Our philosophy was always sustainable fashion. So what people talk of today, we were already thinking of 20 years back. How clothes become heirlooms.

We must promote handicraft and handloom in India and give them as gifts to our children and the future generations because unless we do that craftsmen won’t survive. Lifestyle is too expensive for a craftsman in our country now. Also, Muzaffar and I travel a lot and stay updated about the world, understand the milieu of today and keep it in sync with our philosophy and that helped us a lot. Sama brought in her freshness but it is fortunate that she stuck to our philosophy of design of creating heirloom pieces.

Vintage, classic, timeless but also catering to the contemporary. The label is now a product of three creative people of various backgrounds. How do you express you individuality through your passion that is a blend of so many creative minds?

Meera: Sometimes it is difficult you know. Because we are three different generations of people working together. My daughter is very strong-minded and is sure of what she wants. And if she feels she is trying to put her foot down in something that she is weak and if either of us tell her that, she is very quick to accept that and change. Both of us have our own involvement. All three of us are like water and we just fill in the spaces.

What interested you about the fine crafts of chikan, aari and zardozi…

Meera: When we started out chikan was really exploited... women were suffering. Muzaffar had made the film Anjuman then. At the same time my manager knew how to do chikan embroidery, so everything fell into place. What happens with crafts is it needs a very strong design input otherwise the craftsperson ends up making the same thing for 40 years and nobody notices anything. Like what happened in Kashmir, until a new input was given. Even Jaipur survived because of so much international input. That’s what we were doing with chikan. Used new blocks, new designs and tried to revive it. Besides that Muzaffar’s mother had a group of aari and zardozi women in the house who were constantly making those embroidery for her in the house. Children of those families were doing the same thing sitting at home. So, we incorporated these two. These were the famous crafts of Lucknow. The young people don’t want to do it anymore that is how the craft is dying at other places. But I see in Bengal people are still doing it.

It started out with a two-fold mission revival of traditional craft and empowerment through rural employment. What has been the the label’s influence in the lives of people of Kotwara in the past three decades and in what ways did it contribute in development through its practices?

Meera: I think it was phenomenal. We were able to stop migration. People leave their homes in search of jobs. When we were young we were told that 20 per cent of India lives in cities, rest in villages. Then it became 25 and 75. Now it is 60, 40. And they say in another decade it will be 50-50. What’s happening is people are moving into cities where they have no identity, they are looking for jobs, doing horrible jobs and living a very transient life. Even if you have a great job, you are still a migrant. Our philosophy was to stem migration and we lead through the women; if they get a job and can supplement the earnings at home then the man need not leave the house and when this reverse migration happened there was hardly anyone leaving for work.

Secondly, since we work largely with women it helped delaying their marriage at a young age. They weren’t getting married at 13 or 14 anymore because that is when she started learning work and wanted to wait for two-three years to earn money. So it empowered the women. Once she is in power, she could tell her family that I don’t want to get married to this drunkard in the colony. That was a great revolution in my mind. It happened and is still happening. I am very happy this happened.

As a fashion house Kotwara had never felt the need to conform to the previously prevalent norms of the fashion and glamour industry and was way ahead of its time in many ways. What’s next?

Meera: Things evolve as they go. I think we want to inculcate a sense of pride in people about continuing to do what they are doing. It is very difficult to sustain just on the craft. That means to sustain we have to pay them better, give them a better lifestyle and their children better education... so prices go up automatically. So, we have to educate the people who are buying that they are buying history, they are giving a future to someone who doesn’t have that future. So that they understand where they are investing.

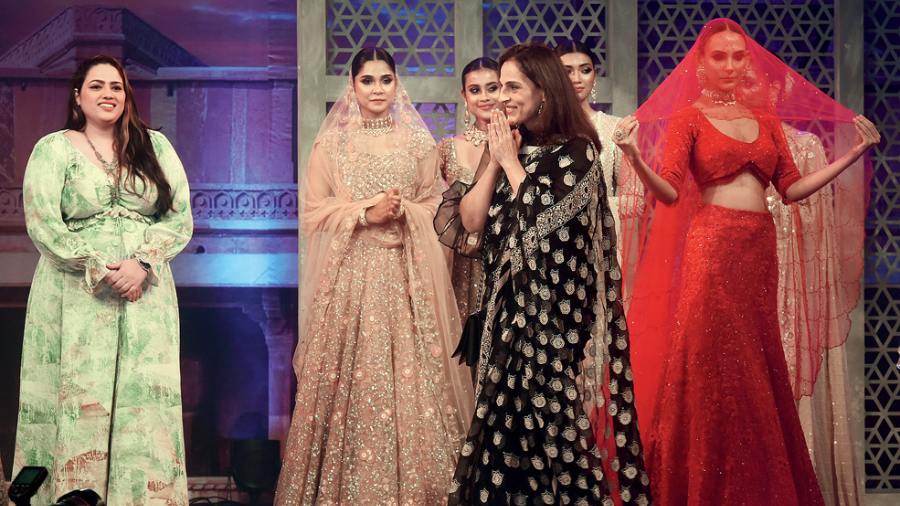

Pictures: Karam Puri and Pabitra Das

Glimpses from ITC Royal Bengal’s Stateroom after the presentation of the recent Ladies Study Group event Weaver of Dreams: The Passion of Muzaffar Ali.

When I was making Gaman, Smita (Patil) said you keep thinking about these people why don’t you do something. My father passed away and just before that I had met Meera. I think Meera added a new dimension to my life, a new impetus for my entry to Kotwara and the only way I could think of helping Kotwara was through the needle and thread and to empower these women with needle and thread. It was a challenge to look after these women designing their future; what you see today and what you will see in the time to come is our ongoing creative quest of what we can do with the needle and the thread. It is a very serious challenge. And we wanted to convey people to make sure that Indian craft survives and the handmade survives. We have to have a very high sense of aesthetics to make Indian craft survive. You can’t treat it in a commonplace manner. Indian craft has to be a global statement — Muzaffar Ali at Weaver of Dreams